Learn advanced research skills with Professor Lisa DeLuca in the new Graduate Student Lounge! Master Google Scholar and our newest research tool, Browzine. This Tuesday, September 22nd from 4:30-5:30pm.

Month: September 2015

Moving the Jennings Petroglyph: Behind the Scenes

By Allison Stevens, Collections Manager | 9/8/2015

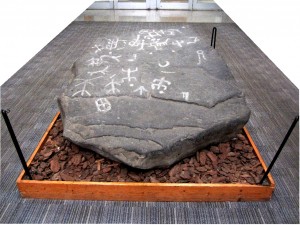

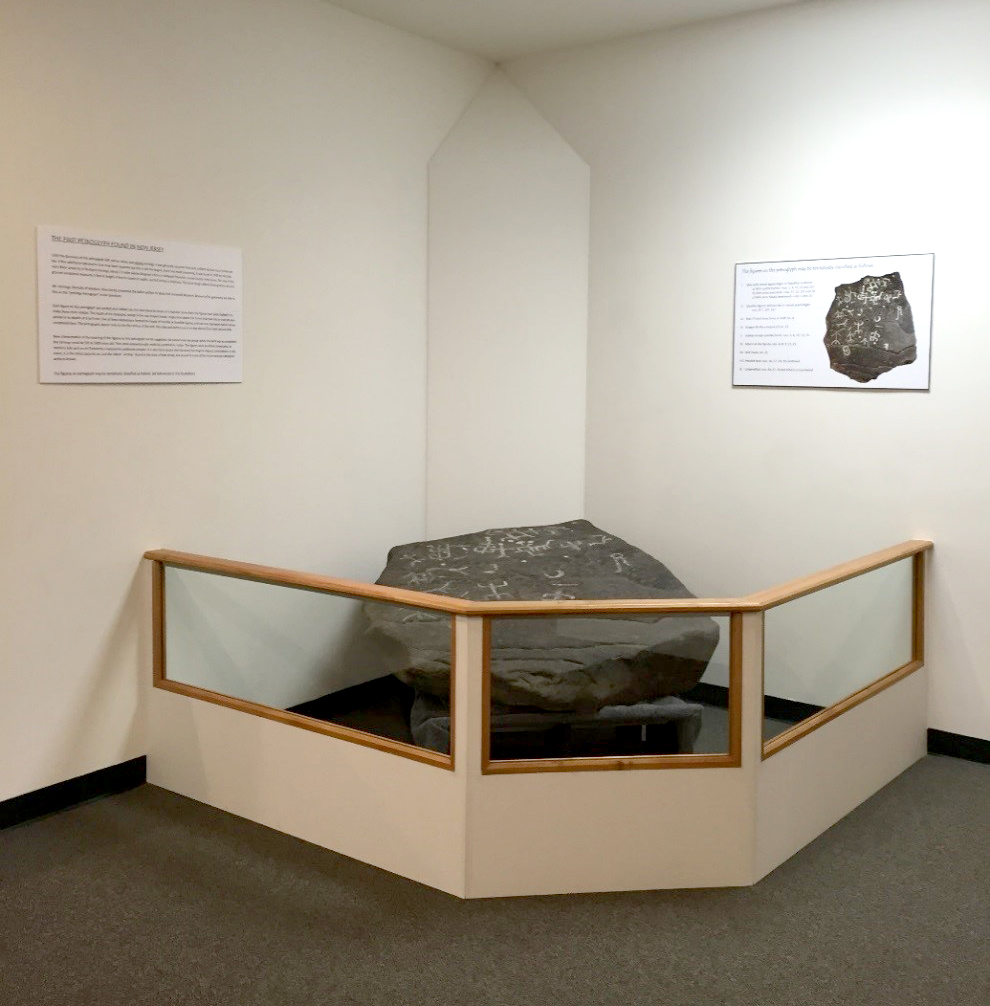

Since 1968, the lobby of Fahy Hall had been the home of the Jennings Petroglyph on the campus of Seton Hall University. On August 19, 2015, it moved to its new home on the main floor of the Walsh Library, just outside the Dean’s suite.

The petroglyph, a Native American artifact probably carved between 1,000 and 5,000 years ago, was discovered across from Dingmans Ferry in Pike County on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River in 1965. Plans to build the Tocks Island Dam, which never came to fruition, would have covered the petroglyph with a lake formed behind the dam. In order to preserve it, the petroglyph was transported to Seton Hall in 1968. The site where this petroglyph was found holds the unique distinction of being the only one ever discovered along the Delaware River.

The word petroglyph means “rock carving,” from petro, meaning “rock” and glyph, meaning “symbol.” Similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs, the symbols are used to convey meaning. Because creating petroglyphs was a difficult and time consuming process, requiring specialized tools for Native Americans to carve into the rocks, we know that their meaning is important. The meaning of the Jennings Petroglyph has been obscured over time, but it is most likely sacred. Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures and cupules (dots and circles) are distinctive elements of this petroglyph. Herbert Kraft (1927 – 2000), Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Seton Hall University, described the glyphs as lizard-like figures or men with sexual appendages.

As Collections Manager, part of my job is to document any major relocation and installation of art and artifacts on campus. Record-keeping is one of the most important aspects of museum collections work; it ensures that future generations will understand the “who, what, when, where, why, and how” something was done with the collection, as well as allow us to track the condition of objects through time. The photographs included show the various stages of the move, and the finished casework in the Walsh Library.

Moving the petroglyph was done for several reasons: to make it more accessible by putting it in a space shared by all students, the Walsh Library; to update the display which had been in place for 47 years; to free up space in Fahy Hall’s lobby; and to unite the petroglyph with the rest of the Seton Hall University Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology (SHUMAA) collection, which will be moving to a newly renovated storage area in the library. Relocating the petroglyph is the first step in this multi-year process to document, catalog, photograph, and properly store the some 26,000 objects in the SHUMAA collection, mostly Native American artifacts, to meet museum standards and to make research easier and more transparent for faculty, students, and scholars alike.

The cataloging of the SHUMAA collection will expand upon work spearheaded by Professor Rhonda Quinn, Assistant Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work at Seton Hall. Through diligent work over the past few years, Dr. Quinn and her students were able to digitize a few thousand of the original paper records created by Herbert Kraft on the artifacts into a museum collections database. Taking over these tasks as Collections Manager, I will continue the process of rediscovery of the significant and culturally invaluable artifacts in the SHUMAA collection. In addition to the petroglyph, the collection is comprised of several thousand lithic materials (stone tools and chipped stone artifacts), pottery sherds, moccasins, a headdress, textiles, clothing, woven baskets, clay pots, jewelry, and many other artifacts.

The move of the petroglyph itself required a team of art handlers, specialized equipment, and a few months of planning between several departments on campus. Walsh Library and Gallery staff met with art handlers to plan the move, Facilities Engineering to make sure that the proposed space in the library met ADA requirements for accessibility, and a structural engineer to ensure that the building could bear the weight of a one ton rock. In addition, the South Orange Fire Marshall had to inspect the space to make sure it met fire code regulations. It also meant coordinating with the Dean of Arts and Sciences, Dr. Chrysanthy Grieco, and her staff to confirm that the schedule worked with both Fahy Hall and the Walsh Library.

Now that the Jennings Petroglyph is in its new home, we welcome you to come visit and form your own ideas about the meaning behind these enigmatic, sacred carvings.

For further reading on petroglyphs, see the Pennsylvania Museum and Historical Commission website: http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/petroglyphs/3892.