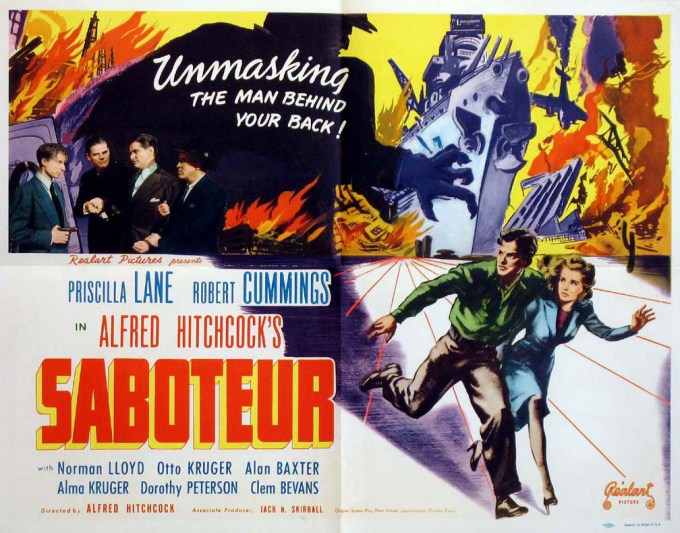

Alfred Hitchcock’s latest film, Saboteur, follows the trek of a Los Angeles-based factory worker to New York City to clear his name after being framed for a crime that would earn him the death penalty: sabotage. In Barry Kane’s 1942 travels, he comes across a series of familiar faces to the American home front – a friendly truck driver, a band of circus performers, high-brow Wall Street elites, an old farmer, local policemen, and a famous model.

Kane, portrayed by Robert Cummings, is framed in the first several minutes of the movie for starting a fire that burned an airplane manufacturing facility in Los Angeles, where he worked. He immediately suspects a fellow worker, Frank Fry, of the crime and hitches a ride with an unsuspecting truck driver to get to a large ranch in the High Desert of California – the place he recalled from a postcard as Fry’s address. A man with a target on his back, Kane jumps through hoops to avoid local police, who, although law-abiding public servants, are portrayed as the perpetrators of this false accusation.

Upon arriving in the Tobin Ranch in the High Desert, (the location indicated on the postcard), Kane immediately flees the home of Charles Tobin, an accomplice of Fry’s, and is arrested by local police. When he breaks free of the grasp of the policemen, with the help of the friendly truck driver, Kane slips into the forest, still handcuffed, and finds his way to a blind old man’s home in the woods. The kind-natured man refuses to turn Kane over to the police upon the request of his niece, Pat, portrayed by Priscilla Lane. His belief in Kane’s innocence is unwavering, despite the criticisms from his niece.

Instructed to deliver Kane to a blacksmith who will remove his handcuffs, Pat has other ideas – she plans to turn him in. She and Kane struggle for control of the steering wheel and wind up in the desert with a broken engine in the dark. Still on opposing sides, they hurl themselves onto a circus train, where the circus performers vote on what to do with Kane. They majority believe Kane to be innocent and decide to hide him from police. One performer expresses warm recognition of Pat’s apparent “loyalty” to Kane, by helping the refugee and never wavering from his side.

This sparks a change in Pat. She vows to assist Kane in his mission to prove his innocence and prevent a future sabotage. In the film’s climax they wind up in New York and come face to face with the saboteurs themselves. Together Pat and Kane prevent the explosion of a naval ship, the USS Alaska, docked in the Brooklyn harbor. A madcap sequence of events leads Kane to a direct confrontation with his enemy, the traitorous Fry, atop the Statue of Liberty – a fitting spot for a showdown between a symbol of American democracy and heroism (Kane) and a symbol of fear-mongering totalitarianism (Fry).

Unlike other wartime films Saboteur does not dehumanize the enemy. It constructs him as a familiar threat, but unifies the heroes with one clear belief: that to defend the country, we must stand together and trust one another. But the conundrum here is that the enemy disguises himself as a familiar face. The protagonist must always be asking himself who to trust.

Hitchcock’s drama evokes similar emotions to the narrative of the American experience in the war to date. At first, the fight against a totalitarian regime looks hopeless. The villains are portrayed to look inconspicuous, even familiar. In this story, a main conspirator, Tobin, appears as a grandfatherly farmer. Partnered with an elitist New York woman known as Ms. Sutton, they control the trust of the New York Police Department and the public. Yet behind closed doors, they’re conspiring to undermine the war effort by killing U.S. citizens and soldiers. They are trying to undo the hard work of American businesses, soldiers and workers, by setting fire to a manufacturing plant, injuring innocent people, and creating a message out of massive destruction. Blaming the fire on Kane establishes a distrust between the humble worker and the police force, effectively barring unity and patriotism, it risks the very survival of the nation and its war effort.

When Tobin and Kane confront each other toward the end of the movie, Tobin expresses his motives: to harness power over the “moron millions” and access the greatest profit and control of the country. “There are a few of us that are unwilling to just troop along,” says Tobin. “A few of us who are clever enough to see that there’s much more to be done than just live small, complacent lives. A few of us in America who desire a more profitable type of government. When you think about it, Mr. Kane, the competence of totalitarian nations is much higher than ours.” With the constant losses in the Pacific and the Atlantic, many in the U.S. and Great Britain fear that the war may drag on for years, or even end in a Axis victory. Tobin’s words could accurately reflect the attitude of many doubtful Americans seeing their ships sunk and their men killed by the seemingly unstoppable German and Japanese forces.

Kane responds in word and action to Tobin’s fearful words, echoing the need for unity and hope among the American people: “There are a lot of people on my side. Millions of us in every country. And we’re not soft – we’re plenty strong. And we’re standing up on our two feet and we’ll win. Remember that, Mr. Tobin, no matter what you guys do. We’ll win if it takes from now until the cows come home.”

Hitchcock, through Barry Kane, reminds the audience why we are fighting – for democracy, for freedom, for the right to escape corruption. He reminds us that the fight is long and arduous, but that it is never over until we’ve come home.