By Brianna Martin and Dominique McIndoe

The idea of men and women serving in the military, side-by-side, is revolutionary and, to some, improper. But a version of this reality is slowly coming to fruition in the United States through the creation of women’s military reserves.

With all available men needed for combat assignments, the military – much like the civilian work force – has a shortage of personnel to perform support duties. To fill these positions, the armed forces are seeking out women.

Although men will continue to do the fighting, the army has opened its doors to women wishing to serve their country in the form of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAACs). The work of this new army contingent includes some of the most important jobs of the war outside of the battlefield including clerical, mess, transportation, and mechanical work that can be done by women as well as men.

The WAAC program was introduced in 1941 in a bill by Massachusetts representative Edith Nourse Rogers. Following the start of US involvement in the war the bill became law on May 15, 1942 and the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps was born.

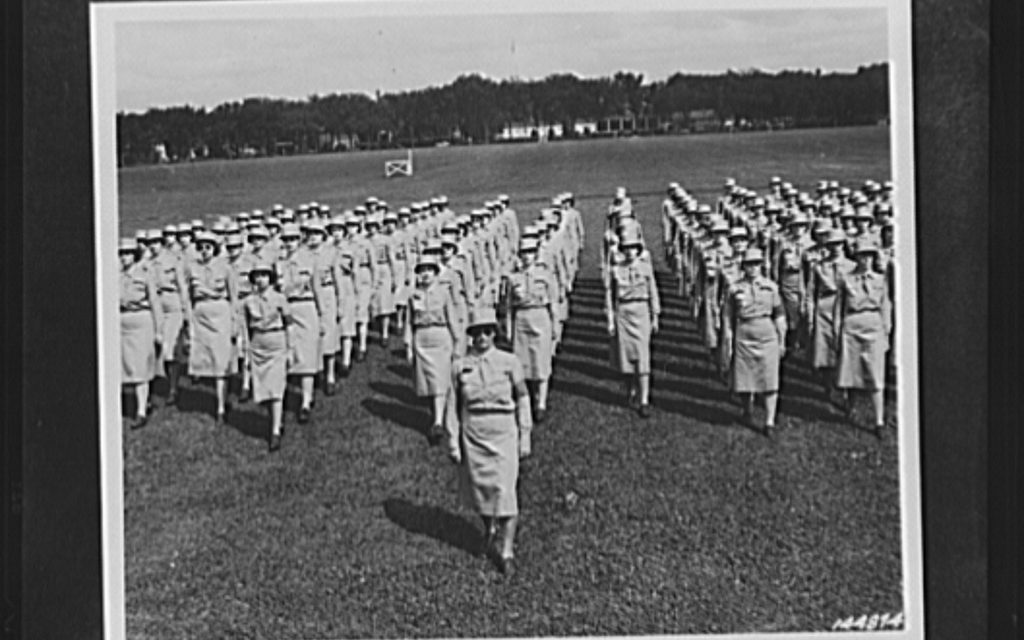

With the advent of this new army program, hundreds of locations where troops are stationed across the US have put in bids for WAACs graduating from the training center in Des Moines, Iowa to join their ranks. Women who enroll in the WAAC program all begin their military careers by entering training in Des Moines. There they learn the essential skills they will need at the various posts they’ll be sent to after graduation.

It is estimated that over 25,000 WAACs will have graduated from the training center by the end of 1943. With the rate at which the US army is growing, it is clear that the need for WAACs—and their opportunities for women to serve their country—will continue to increase.

Director of the WAACs, Oveta Culp Hobby, worked closely with the first women who graduated from the Des Moines training center. Hobby spoke at the graduation of the first round of WAACs, stressing the drastic change in their lives now that they have entered into military service. “You have taken off silk to put on khaki. You have a debt to democracy and a date with destiny. You may be called upon to give your lives.” Before taking over as Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps director, Hobby headed the War Department’s Women’s Interest Section.

WAACs are involved in much more than typical clerical and mechanical work – special stage productions are often put on by the WAACs and some of their male counterparts. The purpose of these productions is often different. Sometimes the plays and musical numbers produced by the WAACs aim to raise morale within the armed forces during wartime. Other times, like in the case of a Rockford, Illinois production called We’re Tellin You, performances for local citizens raise money for the war efforts. That particular show raised almost $200,000 and dazzled audiences.

With the success of the WAACs in both military and morale-boosting efforts other branches of the military have begun exploring the concept of employing women.

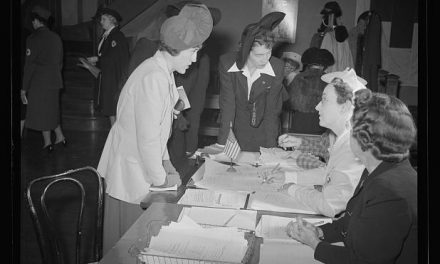

Since the beginning of U.S. involvement in the war, legislation has passed through Congress and the White House for concurrence on a bill to create a women’s navy reserve. The bill’s development wasn’t smooth, as the Senate and the House sought to duplicate that of the women’s army corps. The Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, also dubbed WAVES, was officially created on July 30 by President Roosevelt’s written approval.

As the WAVES begin to recruit and establish themselves as a branch, there has been dissent. But military officials have expressed their support for it.

“There is an immediate and pressing need for these women,” said Captain Kenneth G. Castlman, director of the Office of Naval Procurement.

The purpose of creating this navy women’s corps is for members to serve as “direct replacements.” They will take over vacant, noncombatant duties on the home front and male enlisted and commissioned personnel will be released for duty at sea, according to Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs, chief of the Bureau of Naval Personnel. The training of reserve applicants as officers and enlisted servicewomen begins in October and lasts for at least one month. Their duties will include cryptography, clerical work, courier service, radio operation, business, geography, and teaching.

Lieut. Comdr. Mildred H. McAfee, the new leader of the WAVES and the first female naval officer in US military history, expressed her excitement about many women’s commitment to serving the country.

“You know the thing that has impressed me most is the enthusiasm that the applicants are showing in trying to get these jobs,” she said. “American women have responded so splendidly to the Navy’s call for volunteers… They are sincere and earnest in their desire to help their country by replacing men who can then be sent to combat service.”

Women’s aspiration to join the WAVES is apparent through the thousands of letters and requests for applications to join that have swamped the Office of Naval Procurement in the past three weeks. The Navy’s original quota is to commission 1,000 officers and enlist 11,000, but due to the high demand, Congress has not made any official law to limit the amount of women who can be accepted into the reserve.

Although the Women’s Navy Reserve has commonalities with its sister Army auxiliary, the WAACs, the WAVES differ in organizational structure, duties, and income. WAACs are permitted to serve in overseas positions while WAVES will be limited to the confines of the United States. However, WAVES will receive equal pay to their male counterparts and carry the same organizational ranks as the male Navy. They are essentially under the same rules and regulations because of their “direct replacement” status. WAACs do not have equal pay to male army servicemen because of the different rank and duty structures. Neither WAVES nor WAACs are entitled to death and disability compensation like male servicemen.

In spite of constant deliberation and changes made to the reserve act leading up to its adoption, the reluctance of some shore stations to hire women, and no mention of the inclusion of black women in organizational plans of either auxiliary, the WAACs and the WAVES are a step toward social change and are unquestionably a much needed force for the war effort on all fronts.

Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox stated that women’s efforts since the start of the war have had a tremendous effect on American society. The creation of these military reserves only reaffirms this notion.

“In today’s total war women play a larger part than in any previous conflict in history – in civilian defense, in Red Cross and in other relief work, in maintaining local morale and directing community effort and [now] even in active war duty,” he said.

McAfee shared similar sentiments: “Women are destined to play a larger part in the affairs of this country… For democracy’s survival depends upon the voluntary cooperation of all citizens in serving the common welfare.”

Sources:

“Training of WAVES will start Oct. 9.” The New York Times, August 21, 1942, p. 13.

Sadler, Christine. “Technical Training May Be a Snag; Uniforms Chosen: WAVES Program May Hit a Snag.” The Washington Post, August 4, 1942, p. 1.

“Senate Approves Women’s Navy Unit: Senate Passes Women’s Navy Reserve Bill.” The Washington Post, July 3, 1942, p. 1.

Woolf, S.J. “She Rules the WAVES: Portrait of Lieut. Comdr. Mildred McAfee of Wellesley.” The New York Times, August 16, 1942, p. SM15.

“Nine Leaving Today for WAAC Training.” The New York Times, August 1, 1942, p. 7.

“WAVES May Enlist More Than 11,000; Navy Says First Group’s Work Will Decide.” The New York Times, August 11, 1942, p. 22.

“New Aides Named To WAVES Staff: Virginia Carlin of New York and Dorothy Foster of Atlanta Made Headquarters Officers.” The New York Times, August 8, 1942, p. 7.

Baldwin, Nona. “Senators Favor Women’s Navy Unit: Committee Reports the Walsh Measure to Set Up A Reserve Force.” The New York Times, Jun. 24, 1942, p. 16.

“WAVES Applicants Swamp the Navy.” The New York Times, August 13, 1942, p. 22.

Baldwin, Nona. “Women Navy Corps Will Enroll 11,000.” The New York Times, July 31, 1942, p. 7.

Sadler, Christine. “Navy Wants Women ‘in’ It, Not ‘With’ It.” The Washington Post, June 13, 1942, p. 25.

Baldwin, Nona. “Miss McAfee Sworn as Head of WAVES.” The New York Times, August 4, 1942, p. 14.

Baldwin, Nona. “Women May Face Active War Duty.” The New York Times, January 19, 1942, p. 14.

Baldwin, Nona. “High Standards Set For Navy Women.” The New York Times, August 1, 1942, p. 13.

“Race Goes Unmentioned in Organization Plans for Proposed Naval Reserve.” The Pittsburgh Courier, August 8, 1942, p. 10.

Sadler, Christine. “Women Fight for Wartime Equality.” The Washington Post, August 16, 1942, p. B5.

“Many Aspire to WAVES: Applications Pour in to Navy from Women Candidates.” The New York Times, August 4, 1942, p. 14.

“1,000 Women Seek Navy Reserve Jobs: Action Delayed Till the Proper Application Forms Arrive.” The New York Times, August 2, 1942, p. 13.

“First Women Soldiers Join Army.” Life, September 7, 1942, p. 75.

“WAACs Take Part in First Review.” New York Times, August 9, 1942, p. 39.

“WAACs Make Stage Debut.” Life, May 31, 1942, p. 26.