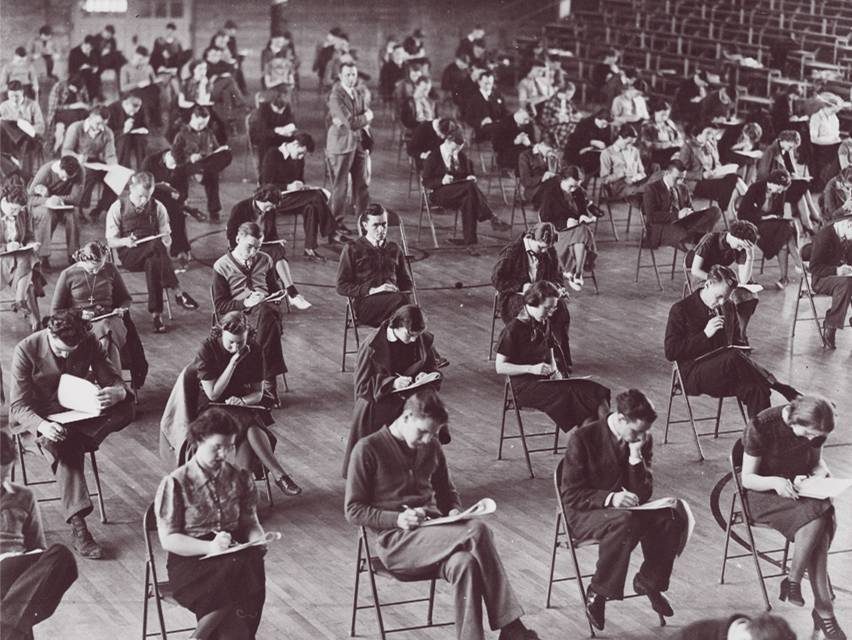

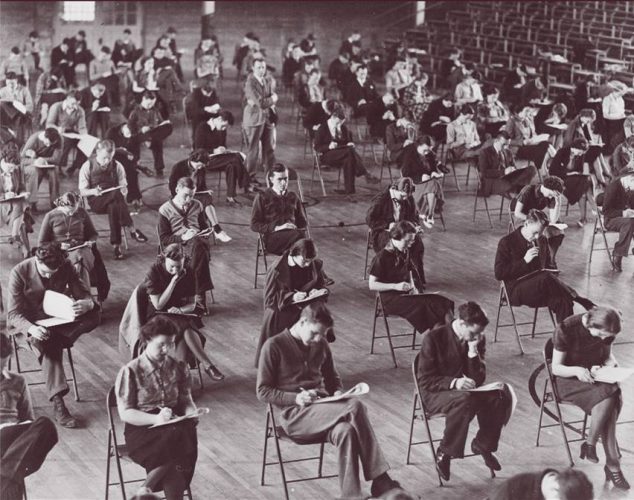

College students taking their final exams at Hamline University in Minnesota.

In this time of crisis, nearly every sector of American society has undergone drastic and sudden changes. Institutions of higher education are no exception. Most notably, many colleges and universities are altering the curriculum to reduce the traditional time of four years to acquire a bachelor’s degree.

Many incoming male freshmen can now expect to graduate and be ready for war by the age of 20. Just last month, University of Chicago president Robert M. Hutchins announced a new two-year program for students to earn their bachelor’s. This is the university’s most startling move since the “Chicago Plan” twelve years ago, in which students could graduate in as little time as desired, so long as they passed their examinations (although few did so in a little as two years). Unorthodox as it is, hundreds of other universities are following the University of Chicago’s lead.

University of Maryland’s wartime curriculum went into effect last week. As at Chicago, incoming freshmen can complete their degrees in as little as two years. The accelerated programs will operate with three semesters per year as opposed to the traditional two. Summer vacations will consist of three weeks rather than the usual three months. The school will only offer breaks on five holidays: July Fourth, Thanksgiving Day, Christmas, Presidents Day and Easter. Dr. H. C. Byrd, University president, said this accelerated program will allow most students to complete their education by age 20, when they will be subject to the draft. University of Maryland is also providing ROTC training and Centennial Aviation Academy (CAA) pilot training courses.

Holy Cross College in Massachusetts has also altered its curriculum significantly. The school has removed certain old programs and added many new courses adapted to the nation’s officer training needs. The majority of these programs fall within the fields of mathematics, physics and related sciences. Many incoming freshmen have already registered in the college’s ROTC Naval V-5 and V-7 programs. Approximately 85 percent of the college’s student body is taking advantage of these naval programs. The number of incoming freshmen is so large that seniors are being assigned as instructors to freshmen. The college has also prepared a series of courses to familiarize students with the war, in which diplomatic history is interwoven with subjects like Ibero-American history, military history and geography.

Catholic University in Washington, D.C, provides another example. It will now award bachelor’s degrees in three years to conform to the war effort. This fast-paced approach will require shortening Easter vacations for students and advancing graduation ceremonies to May rather than June. The accelerated program was recommended by the chairman of the school’s Council of National Defense, Dr. Martin R.P. McGuire, and accepted as a contribution the university wanted to make to the nation’s war program.

The decrease in degree-completion times continues to spread, driven in large part by the government’s decision to begin conscription at age 20. At most colleges, the establishment of summer terms is making accelerated programs possible. Not to be confused with summer schools, these terms will be treated as the equivalent of a fall or spring semester.

University faculty believe the new adjustments to curriculum are necessary to meet the wartime challenge. “We are educating youth not only for war efforts, but for peace and reconstruction,” said Dr. Merle Curti, a history professor at Columbia University, on Jan. 25 at a general session of the college in which faculty discussed education programs.

“Education will make no significant contribution to democracy if it continues to teach the traditional curriculum,” said Thomas H. Briggs, author and professor at Columbia University, Briggs said that the primary need is for people to clarify an understating to themselves and to their pupils of the meanings of democracy.

Some colleges, however, are supporting the war effort without accelerating the degree completion itself. The all-female Barnard College has found alternate ways to speed up study. A select amount of college freshmen will be eligible to begin school as early as July and August. “[This is] providing special lengthened courses for [students] so that they can get approximately a regular term’s credit for their summer work,” said Dean Virginia C. Gildersleeve. Although Barnard will not offer the acceleration of degree completion that many universities are exercising, the college will have special advisers to guide students in their individual contributions toward winning the war.

This new approach that is taking over university life, despite its potential benefits for the war effort, has some educators concerned. There is a fear that decreasing the full four years of education may reduce standards of universities, lower their credentials, and drop expectations of excellence for students. Last month, during the first National Conference of College and University Presidents, in Baltimore, approximately 1,000 university presidents met to discuss the role of higher-education institutions in wartime–accelerated education was the subject of the most debate. Throughout the long discussion, many educators emphasized that accelerated programs will have large effects on the entire field of higher education. John W. Studebaker, U.S. Commissioner of Education, predicted that these plans will impact the future of college education by shifting more concentration to world geography, economics and foreign languages. “Isolation is gone for good in the United States,” said Studebaker. He said that as educators reexamine their curricula, they will continue to shift many of their provincial aspects in courses.

After long debate, the biggest decision that emerged from the conference was approval of an accelerated three-year program, which approximately 1,000 colleges will adopt.

The number of educational institutions actively supporting the war effort is expected to increase as the war continues to develop.

Sources:

“Holy Cross Shifts to War Curriculum.” New York Times, Feb 8, 1942.

“Ohio Includes Chinese in New War Curricula.” New York Times, Feb 1, 1942.

“Columbia to Revise its Program for War; Military, Governmental Courses Stressed.” New York Times, Jan 4, 1942.

FELIX M, “Colleges Hit by the War; 3-Year Courses, Summer Sessions Urged.” Wall Street Journal, Jan 17, 1942.

“BARNARD PLANNING TO SPEED UP STUDY.” New York Times, Jan 14, 1942.