Not all the essential tasks of war are completed on the battlefield by men in uniform. Even a stay-at-home mother from a small town can find a way to influence the war and provide for her country in its time of greatest need. Angelina Alexandre is one example of a growing trend among American women who put the needs of their country before their own by going to work.

The daughter of Mexican immigrants, Angelina Alexandre was born on February 20, 1919, and raised in Merced, California, along with her ten siblings. Alexandre recalls fondly growing up in Merced, which she remembers as a beautiful place filled with endless possibilities.

Her father worked with cattle, riding horses and always carrying a Mexican flag on his horse. Alexandre’s father ingrained in her and her siblings that America was a land of opportunity and growth and that they were lucky to be there, but they were also encouraged to take pride in their Mexican heritage.

Following the death of her father when she was a teenager, Angelina and her siblings set out to work in order to keep the family afloat. They would perform odd jobs including wine making, canning, and tree pruning. The difficulty came in the winter when less work was available and the family was forced to live off of funds saved from the summer season. Alexandre explained that in the wintertime all they typically had was flour and rice to eat. “That’s the way that you could survive all those months. Big sack of beans, flour, you name it. And so that’s the way we used to have the wintertime, rice, macaroni, sacks of flour.”

By 1938, at age 19, Angelina was introduced to her future husband. He, like her parents, was an immigrant from Mexico working and living in California. Her husband works mainly on the railroad and has for most of his life, so when they got married, Alexandre moved in with him in the town of Needles, California to be closer to his job.

Alexandre noted that her husband is one of the hardest workers she knows, reminding her of her father and siblings who always worked hard in order to provide for their family.

While Merced, where Alexandre grew, up had very few immigrants, Needles is a completely different story. The families scattered throughout the town seem to Alexandre to represent the nation as a melting pot of different cultures.

Alexandre describes the mingling of different races and cultures and the discrimination they felt from some of the other residents: “I went to a theater one day. And the girl was going to put me by the Indians and the few blacks and the Mexicans to one side. And I told the girl in the flashlight, ‘I’m not going to sit over there! I want to sit where I feel like sitting.’ And my husband said, ‘Angie, that’s the way they do here.’ I said, ‘Well, I was born and raised here and I sit down in this theater wherever I want to sit.’ The girl didn’t tell me nothing. I sat where I wanted to sit. And I said, ‘If you want to go sit, you go over there, but I’m coming over here.’”

Angelina notes that the discrimination she felt as a Mexican-American fell to the wayside in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, when the racial tension focused solely on those of Japanese descent. Angelina’s husband worked on the railroad with many Japanese men and she remembers his time away from home increasing drastically when the Japanese were rounded up by the government and forced into camps in the surrounding area.

One such camp was in the same neighborhood as the Alexandre home. Angelina remembers the beginnings of the Japanese internment as her neighbors were visited by what she calls “government men” who collected their belongings before taking them away. Most of the women in the Japanese households tried to sell some of their things to Angelina and their other neighbors since they weren’t allowed to take much with them.

Alexandre is careful about going close to the camp, explaining that after the attack on Pearl Harbor, she heard some Japanese men saying that they were confident that the Japanese will win the war (she believes the US will prevail).

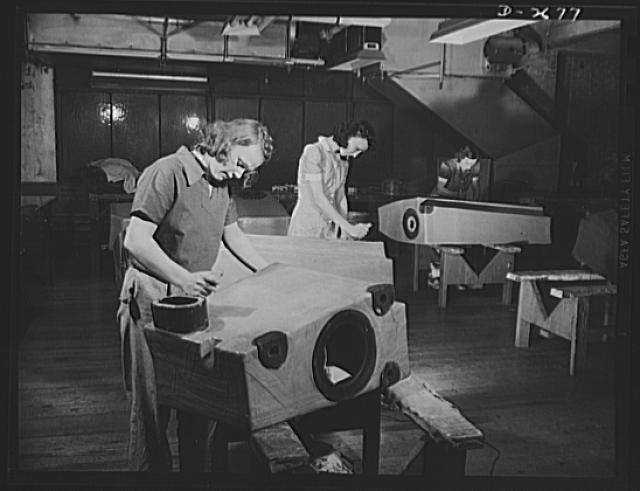

Even with her husband’s increased work responsibilities, Alexandre wanted to help fill the spots left by the men who went to fight for their country. So she got a job working at a Ford Motor plant.

Female factory workers building forms used in the manufacturing of self-sealing fuel tanks. Photo by Alfred T. Palmer, from Library of Congress.

Alexandre’s three children are all still very young, meaning that she has to find someone to watch them while she and her husband are off working. Although she was raised in a home where her mother watched the children at all times, Alexandre maintains that her contribution to manufacturing during the war is more important than making sure her children always have their mother around.

Martha, or as the Alexandre kids call her, “Mammy,” is a neighbor who watches after Angelina’s children while their parents work. Alexandre says at times she wishes she could remain with her children, but she feels that she is doing the work that any American in her position would be happy to do in a time of war.

Angelina Alexandre’s efforts serve as a reminder of the sacrifice that many Americans are making. As she says proudly, “I was born and raised here,” and her efforts during the war thus far have shown how committed she is to the country that she calls home.

Sources:

Angelina Alexandre. Rosie The Riveter World War II American Home Front Oral History Project. Interviewed by Jess Rigelhaupt, 2005. Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, Copyright 2005. http://vm154.lib.berkeley.edu:3002/searchinterview/fullDisplay?data=221622