With the U.S. government determined to regulate wages and prices during wartime, the War Labor Board (WLB) is trying to mediate disputes between employers and disgruntled workers seeking pay increases.

Last week, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins brought forward a case involves over 30,000 workers at the industrial giant Aluminum Corp. of American (Alcoa). The workers belong to three unions under the umbrella of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO): the Aluminum Workers, the National Association of Die Casters, and the United Automobile, Aircraft and Agricultural Implement Workers. They are in direct conflict with eight Alcoa plants located in California, Ohio, North Carolina, and elsewhere.

The unions demand a one-dollar-per-day increase in general wages, union security, overtime pay, and increased premium rates of 10 cents per hour, testing how far the WLB is willing to go to aid workers.

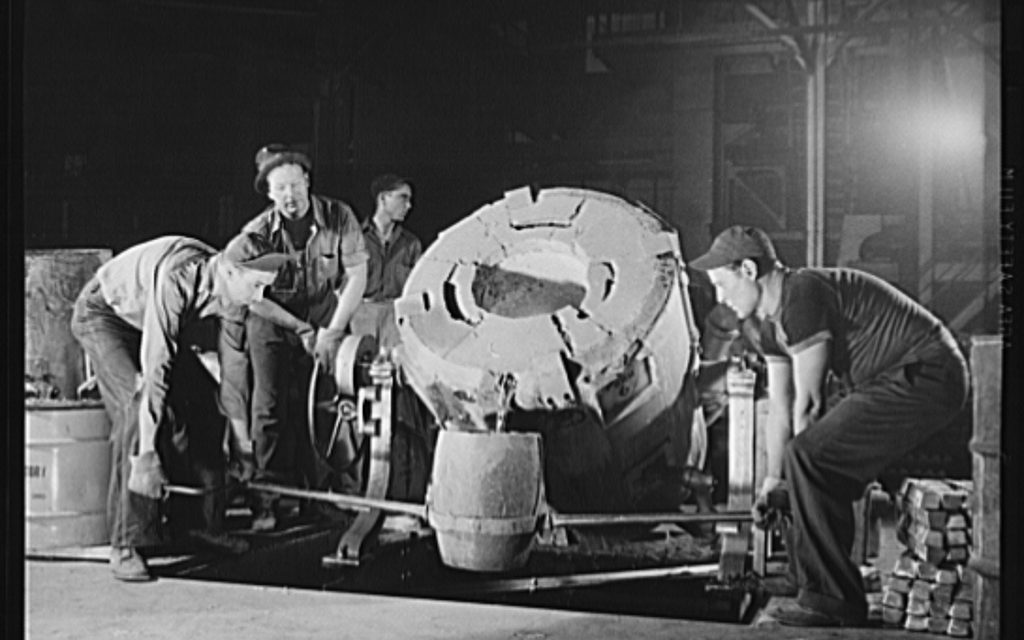

Aluminum workers are demanding a wage increase from Alcoa. In this picture, workers pour molten aluminum from a large crucible furnace at a factory in Cincinnati. Photograph by Alfred T. Palmer, from Library of Congress.

At the same time, the WLB is considering a case involving the Farm Equipment Workers Organizing Committee and Caterpillar Tractor Co., regarding the dismissal of employees; that case is expected to be resolved without issue.

The WLB has heard many such disputes in its short existence. President Roosevelt created the board in January for the purpose of arbitrating labor disputes in a timely manner, to avoid any labor shortages or slow-downs during wartime. In another case involving Alcoa in mid-February, the board voted to gradually eliminate the wage differential among southern aluminum workers and their northern counterparts. Wayne L. Morse of the WLB issued the majority opinion for this first Alcoa case.

The statement concluded, “It is reasonable for labor to demand wages high enough to maintain civilian morale and a good standard of living and to pay taxes. It is unreasonable for labor to expect wages to keep up with all changes in the cost of living or to demand inflationary raises in pay.”

This decision set a crucial precedent for employees during wartime. Although inflation affects daily life, no wage increases can be expected unless civilian morale declines, a “good” standard of living becomes unattainable, or taxes cannot be paid. Now, while employers and employees may both agree with the general statement, the line between reasonable and unreasonable is easily blurred because of the arbitrariness of “good” and “morale” at the center of its distinction.

How will the WLB determine a good standard of living? At what point does morale become low, and how does the government measure that?

The more recent dispute concerns a general increase in wages, directly addressing the WLB’s decision about inflationary increases being unreasonable. The February dispute between southern CIO workers and Alcoa leveled a 7-cent-per-hour differential. There is a significant difference between the 7-cent equalization and this month’s one-dollar-per-hour general wage increase.

The majority opinion in the Alcoa case urged the public to bear in mind that while attempting to meet inflationary trends, the public and the labor force already contribute heavily in taxes. “It is to be remembered that out of the wage envelopes of American workers generally will come a large share of direct and indirect taxes,” Morse wrote.

Sources:

“Labor News: Disputes Involving 50,000 Workers Certified to War Labor Board.” The Wall Street Journal. Mar 3, 1942, p.2.

“Labor News: War Labor Board Condemns Inflationary Wage Demands; Upholds Fair Increases Also Reduces North-South Pay Differential in Aluminum Company Plants.” The Wall Street Journal. Feb 13, 1942, p. 2.

“Waiting in the Wings.” Time. Feb. 23, 1942.