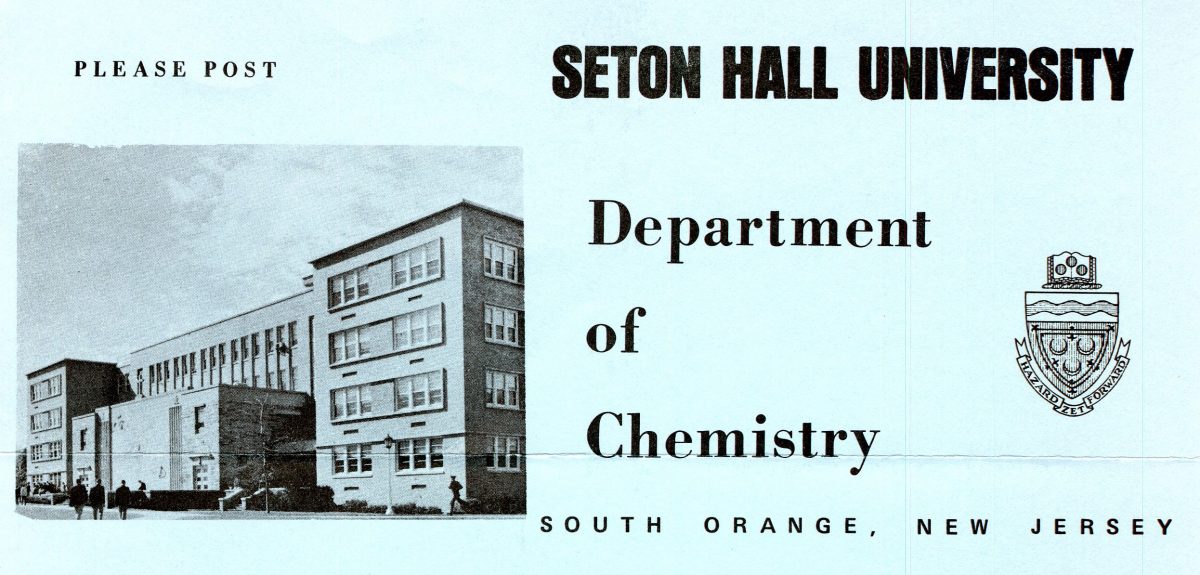

National Hispanic Heritage Month is a celebration and a recognition of contributions to the United States from the Hispanic community. Originated in 1968 under President Lyndon Johnson as a weeklong event, it was expanded to a month in 1988 under President Ronald Reagan, starting September 15 and ending October 15 to coincide with national independence days in several Latin American countries. According to Pew Research, the United States Hispanic population reached 62.5 million in 2021 which would mean the Hispanic community accounts for about 19% of the United States population. Here at Seton Hall University, 21% of the student body is Hispanic along with numerous staff members, administrators, and faculty.

During this month, the Archives and Special Collections Center and the Walsh Gallery would like to showcase collections that highlight Hispanic heritage:

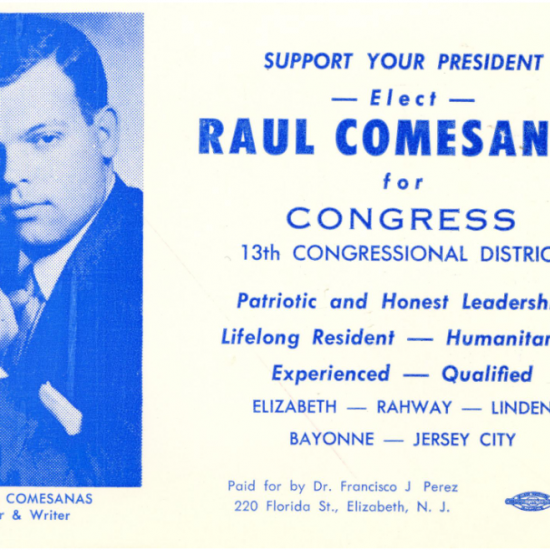

MSS 0130 – Father Raúl Comesañas Papers

The Father Raúl Comesañas Papers is the first bilingual finding aid created by the Archives. These papers document the life, work, and activities of Father Raúl Comesañas, a Roman Catholic priest of the Archdiocese of Newark who was born in Cuba and became a civic advocate for Union City, New Jersey. Below is what the collection contains:

This collection covers materials related to Father Comesañas’s run for the 13th Congressional district of New Jersey, his work as a Catholic priest in New Jersey, and his work as president of the Union of Cuban Exiles (U.C.E.). There is also a variety of background information related to Fr. Comesañas’s political interests including his role on various boards, his post-secondary education and seminary work, and personal correspondence. There is a significant collection of newspapers, including La Nación Americana, El Clarín, La Tribuna, and Vanguardia Católica all of which Fr. Comesañas had a role in the publication or editing of. The remainder of the newspapers in the collection cover news in North New Jersey and is published in English and Spanish.

The collection covers the years 1943, from paperwork and correspondence of Fr. Comesañas’s family prior to arriving in the United States, to 2017, one year before his death.

——————————————————-

Esta colección cubre materiales relacionados a la carrera política para el trece distrito del Congreso de Nueva Jersey, el trabajo como un Padre de la iglesia católica, y el trabajo como presidente de la unión de exiles cubanos (U.C.E.) de Padre Comesañas. También, hay una variedad de información de fondo sobre sus intereses políticos incluyendo su papel en mesas directivas, su educación y trabajo en el seminario, y sus letras personales. Hay una colección significativa de periódicos, incluyendo La Nación Americana, El Clarín, La Tribuna, y Vanguardia Católica, todos en que Padre Comesañas tenía un papel en su publicación o revisión. El resto de los periódicos cubren noticias del norte de Nueva Jersey y se publican en ingles y español.

Los documentos cubren los años de 1943, con documentos de la familia de Padre Comesañas antes de mudarse al Estados Unidos, al 2017, un año antes de la muerte de Padre Comesañas.

Make sure to check out this digital exhibit!

4981 none none true true true Close Next Previous The requested content cannot be loaded. Please try again later.

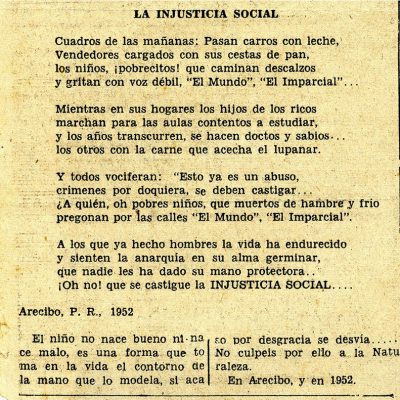

MSS 0020 – Trina Padilla de Sanz papers

The Trina Padilla de Sanz papers covers the writings and correspondence of Trinidad (Trina) Padilla de Sanz, a Puerto Rican poet, suffragist, and composer, known as “La Hija del Caribe” in honor of her father José Gualberto Padilla, a prominent medic, poet, and political activist known as “El Caribe”. Below is what the collection contains:

The Trina Padilla de Sanz papers date from 1845 to 1968, with the majority of records dating from 1902 to 1957, and document the life and literary career of Puerto Rican poet, writer, suffragist, and composer Trina Padilla de Sanz. The collection consists mostly of correspondence, original manuscripts, and printed works and also contains a small number of photographs and family papers.

The collection is arranged into three series: “I. Correspondence, 1845-1957 (Bulk: 1902-1957)”, “II. Writings, 1910-1966 (Bulk: 1910-1956)”, and “III. Personal and family papers, 1905-1968”.

Series “I. Correspondence” dates from 1845 to 1957, with the majority of correspondence dating from 1902 to 1957, and consists of correspondence with friends, family, and notable musicians, poets, politicians, and writers of her day. Prominent correspondents include, but are not limited to: Luis Llorens Torres, a well-respected Puerto Rican poet, playwright, and politician; Luis Muñoz Marin, the first democratically elected governor of Puerto Rico; Cayetano Coll y Toste, an esteemed Puerto Rican historian and writer; José de Diego y Martinez, a statesman and journalist known as the “Father of the Puerto Rican Independence Movement”; Gabriela Mistral, the first Latin American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature; Manuel Fernandez Juncos, a Spanish journalist and poet who wrote the lyrics to Puerto Rico’s official anthem “La Borinqueña”; Braulio Dueño Colón, co-writer of the song series “Canciones Escolares” and lauded as one of Puerto Rico’s greatest composers; and Lola Rodriguez de Tio, the first Puerto Rican-born poetess to achieve widespread acclaim throughout Latin America. Other noteworthy correspondence includes a letter penned by José Gualberto Padilla, known as “El Caribe”, in 1845 and correspondence between La Hija and her son, Angel A. Sanz Padilla, and daughter, Amalia “Malín” Sanz Padilla. This series is arranged alphabetically by correspondent.

Series “II. Writings” dates from 1910 to 1966, with the majority of writings dating from 1910-1956, and consists of articles, essays, poems, short stories, and open letters in both manuscript and printed formats. The series also contains newspaper and magazine clippings of La Hija’s work, writing fragments, and a small number of articles published after her death. Featured in this series are La Hija’s published works in several prominent Puerto Rican magazines, includingAlma Latina,Condor Blanco,Heraldo de la Mujer, andPuerto Rico Ilustrado. This series is arranged alphabetically by title.

Series “III. Personal and family papers” dates from 1905 to 1968 and contains newspaper and magazine clippings related to La Hija and her family, writings about La Hija, photographs, keepsakes and ephemera, a scrapbook documenting La Hija’s musical career, and a small number of papers belonging to her son, Angel A. Sanz Padilla. This series is arranged alphabetically by record type and chronologically thereunder.

This collection will be useful for researchers interested in the social, cultural, political, and economic issues specific to Puerto Rico during the first half of the twentieth century. It provides in-depth insight into a variety of topics of the pressing current events of that era. For researchers focused on the feminist movement, this collection offers insight into the role of women in society, inequality between genders, and domestic affairs. For those interested in the political sphere, La Hija’s writings contain analyses of not only Puerto Rican liberation efforts, but also the dynamic between the country and more powerful foreign influences, specifically the United States. Researchers who wish to study social problems faced by Puerto Rico will find various articles penned by La Hija related to poverty, wealth disparity, divorce, the death penalty, and juvenile delinquency.

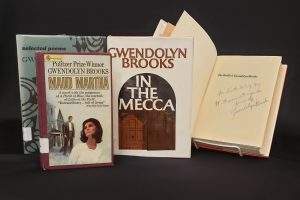

Along with the archival collection, there is a small selection of books that belonged to Trina Padilla de Sanz. Included in these books are works by Hispanic authors such as:

Selección de poesías : Alma América, Fiat lux, Oro de Indias y otras poesías by José Santos Chocano

… Essais by Eugenio María de Hostos, translated by Max Daireaux

Las fronteras de la pasión : novela by Alberto Insúa

Make sure to check out this digital exhibit! And some digitized papers from the collection.

4987 none none true true true Close Next Previous The requested content cannot be loaded. Please try again later.

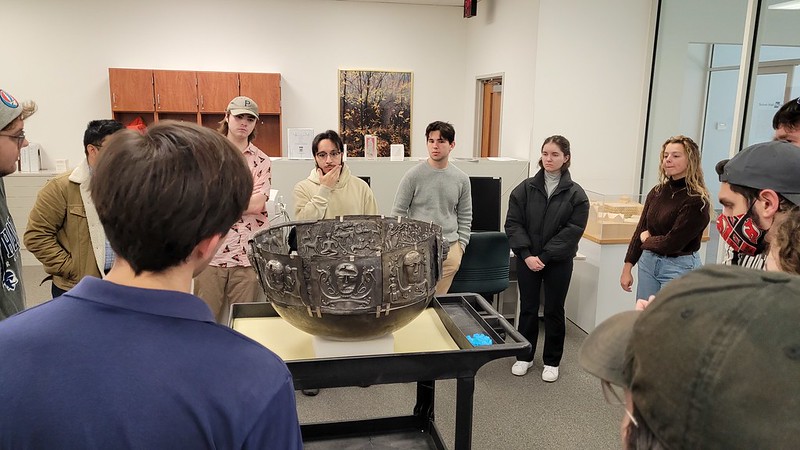

The Walsh Gallery holds many objects from all around the world, from places as close as parks within New Jersey to regions that have since been renamed. Here are a select few objects:

4960 none none true true true Close Next Previous The requested content cannot be loaded. Please try again later.

Make sure to check out this compiled map with more objects from around the world as well as Google Arts and Culture which has over 217 object photos. And stay tuned for the launch of PastPerfect!

If you are interested in using any of these materials as part of your research, please submit a Research Appointment Form.

If you are interested in using these materials as part of a class visit, please archives@shu.edu.