May Day Eve and May Day

Lá Bealtaine in Irish, or “Belltaine or May Day took its name, i.e., bel-tene, lucky fire” is a celebration of summer (Joyce, 290). May Day Eve and May Day are traditionally celebrated with great bonfires along with fairs and festivals. This day also marks the occurrence of a shriek due to the Red Dragon of Britain being attacked by the White Dragon of the Saxons.

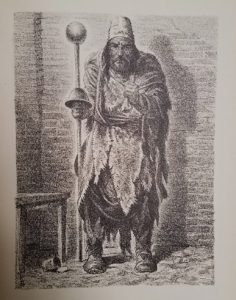

May Day marked “the great feast of Bel, or the Sun”, a time when the “Druids lit the Baal-Tinne, the holy, goodly fire of Baal, the Sun-god, and they drove the cattle on a path made between two fires, and singed them with the flame of a lighted torch, and sometimes they cut them to spill blood, and then burnt the blood as a sacred offering to the Sun-god” (Wilde, 102).

While the Druids saw Bel as a god, Reverend Michael P. Mahon describes Bel as being promiscuously written “Bial and Beal, and supposed to be the “Beel” in the Hebrew word Beelzebub, is a semitic word that would give the idea of a supreme god or a supreme demon” (Mahon, 195).

According to ancient Druid practices all domestic fires were extinguished and relit by the sacred fire taken from the temples and it was “sacrilege to have any fire kindled except from the holy alter flame” (Wilde, 102). It was said that while the sacred fire was burning “no other should be kindled in the country all round, on pain of death” (Joyce, 290).

However, St. Patrick was “determined to break down the power of the Druids; and, therefore, in defiance of their laws, he had a great fire lit on May Eve, when he celebrated the paschal mysteries; and henceforth Easter, or the Feast of the Resurrection, took place of the Baal festival” (Wilde, 102). Thus Christianity started to take root but still boasted similar traditions, customs, and superstitions, just without sacrifice and death. One such superstition talks about fires going out on May Day, stating that:

“If the fires go out on May morning it is considered very unlucky, and it cannot be re-kindled except by a lighted sod brought from the priest’s house. And the ashes of this blessed turf are afterwards sprinkled on the floor and the threshold of the house” (Wilde, 106).

Which is similar to the Druids practice of extinguishing domestic fires and only relighting them from the sacred fire, the holy alter flame, taken from the temples.

And where “Baal fires were originally used for human sacrifices and burnt-offerings of the first-fruits of the cattle”, they were being used “for purification from sin, and as a safeguard against power of the devil” (Wilde, 102). Even with Christianity established people have learned that May Day celebrations are “a survival of the ancient pagan rite” along with certain customs and superstitions (Mahon, 197).

Such as believing that fairies have great power during May Day and children, cattle, milk, and butter must be guarded from their influence. Other customs and superstitions say:

“It is not safe to go on the water the first Monday in May” (Wilde, 106)

“Finishing a cup of nettle soup on May 1 (May Day) prevents rheumatism for a year” (Putzi, 195).

“…the men, women, and children, for the same reason, pass through, or leap over, the sacred fires, and the cattle are driven through the flames of the burning straw on the 1st of May” (W. R. Wilde, 39)

“The fire was of the greatest importance in house in Ireland. People were unwilling to allow it to die out or to lend a fire-coal. They were especially careful of the fire on May Day” (O’Súilleabháin, 334)

“…spent coal must be put under the churn, and another under the cradle; the primroses must be scattered before the door, for the fairies cannot pass the flowers” (Wilde, 102)

“All herbs pulled on May Day Eve have a sacred healing power, if pulled in the name of the Holy Trinity; but if in the name of Satan, they work evil” (Wilde, 184)

While Christianity became more popular and practiced, old time Druid traditions can still be seen. May Day Eve and May Day, as with many other holidays that are celebrated, is a mix of traditions and customs, creating something that is unique and enjoyed by all.

Reference

Joyce, P. W. (1903). A social history of ancient ireland : treating of the government, military system, and law ; religion, learning, and art ; trades, industries, and commerce ; manners, customs, and domestic life, of the ancient irish people. Longmans, Green.

For the online version, click here. Please note they may not be exactly the same.

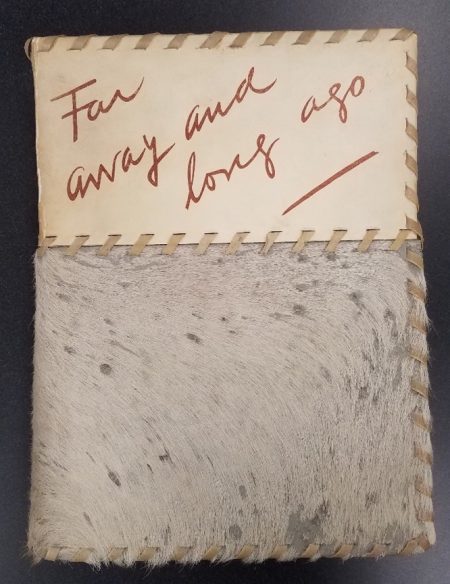

Wilde, & Wilde, W. R. (1919). Ancient legends, mystic charms & superstitions of ireland : with sketches of the irish past. Chatto & Windus.

For the online version, click here. Please note they may not be exactly the same.

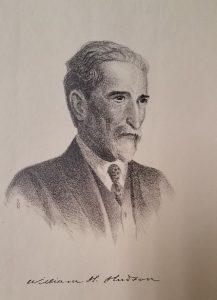

Mahon, M. P. (1919). Ireland’s fairy lore. T.J. Flynn.

For an online version, click here. Please note they may not be exactly the same.

Putzi, S. (Ed.). (2008). To z world superstitions & folklore : 175 countries – spirit worship, curses, mystical characters, folk tales, burial and the dead, animals, food, marriage, good luck, and more. ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Wilde, W. R. (1852). Irish popular superstitions. J. McGlashan.

No online version available.

Squire, C. (191AD). Celtic myth & legend, poetry & romance. Gresham Pub.

For the online version, click here. Please note they may not be exactly the same.

O’Súilleabháin Seán. (1942). A handbook of irish folklore.

No online version available.