Trinidad (Trina) Padilla de Sanz (1864-1957) was a Puerto Rican poet, suffragist, and composer. Her lifetime spanned several of the most defining moments of Puerto Rico’s history, all collected in her writings and correspondence with some of the most influential people in Puerto Rico and Latin America at the time. She adopted the pen name “La Hija del Caribe” in honor of her father José Gualberto Padilla (1829-1896), a prominent medic, poet, and political activist known as “El Caribe”. La Hija enjoyed a prolific literary career over the course of several decades, with her corpus consisting of articles, essays, poems, and short stories on a variety of socio-political, artistic, and musical topics. The Trina Padilla de Sanz papers date from 1845 to 1968, and include personal correspondence, original manuscripts, published works, and photographs. This collection not only depicts the exceptional life of Trina Padilla de Sanz, but also documents a time of great socio-political and cultural change in Puerto Rico.

Photograph of La Hija speaking on the radio surrounded by a crowd. Her son, Angel A. Sanz, is standing to her left. Undated.

Crucial to La Hija’s identity was her connection to her homeland of Puerto Rico. She unwaveringly supported liberation for the island nation and frequently called upon her compatriots to preserve Puerto Rico’s customs and language. While Puerto Rico’s history is intertwined with foreign influence and intervention, its culture and traditions have persevered. La Hija was a loud voice in this movement, proudly defending “La Patria”, or the homeland, for the duration of her life. The following articles written by La Hija reflect her lifelong and passionate defense of Puerto Rico.

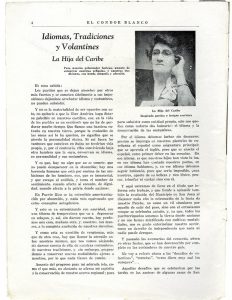

Excerpt of article written by La Hija and published in Condor Blanco, 1946.

“Idiomas, Tradiciones, Y Volantines”

“Los pueblos que se dejan absorber por otros más fuertes y se someten dócilmente a sus imposiciones…no pueden subsistir.”

Translation:

“The nations that let themselves be absorbed by others much stronger and meekly submit to their impositions…cannot survive.”

La Hija used this article as a platform to argue the importance of maintaining Puerto Rico’s language and unique culture when faced with powerful, outside influences. She asserted that Puerto Rico would cease to exist if it let itself be swallowed up by the imposing force of the United States. She understood the importance of a language for one’s identity and that once lost, would open the door to further submission. While recognizing that English should be learned as the global language, Padilla argued that for Puerto Ricans, Spanish should always come first. She called upon her compatriots to never stop defending their native langauge.

“Cuatro sacerdotes norteamericanos se han hecho cargo de la parroquia de la ciudad de Arecibo. Cuatro sacerdotes QUE NO SABEN ESPAÑOL…”

Translation:

“Four North American priests have been put in charge of the parish of the town of Arecibo. Four priests THAT DO NOT KNOW SPANISH…”

This article shows how La Hija’s activism extended to even local affairs. In this piece La Hija lamented the arrival of American priests who displaced Puerto Rican priests in the local parish. She furiously noted that these priests did not speak Spanish and wondered how they could serve their community without this vital means of communication. Although this incident took place at a very local level, for Padilla, it symbolized the larger effort of North American intrusion in Puerto Rican affairs. La Hija did not shy away from addressing actual problems facing her community.

Excerpt of article written by La Hija, October 1930.

“La Pretendida Superioridad De La Raza Sajona Sobre La Raza Latina”

“No hay tal superioridad: Existe solamente un abuso de fuerza…”

Translation:

“There is no such superiority: There exists only an abuse of power…”

La Hija discussed how the Anglo-Saxon race was commonly seen as superior to other races. She immediately dispelled this notion and unequivocally proclaimed that there was no innate superiority, simply an abuse of power that created drastic imbalances between nations. Writing in 1934, La Hija was aware of the dangers of this mindset. The remainder of the twentieth century would bear witness to countless interventions by the United States in Latin American affairs often with disastrous and long-lasting consequences and under the guise of superiority. La Hija was well aware of the strength of Puerto Rico’s influential neighbor and was willing to speak out.

Article by La Hija featured in Tricolor, undated.

“El Caso De Puerto Rico”

“…Cuando en el mundo se advierte un enorme soplo de libertad…en nuestra desdichada patria hay, por el contrario, un ambiente enrarecido que no da paso a la serenidad de las ideas.”

Translation:

“…When an enormous breath of liberty is observed throughout the world…in our unhappy homeland there is, on the contrary, a charged atmosphere that does not give way to the serenity of ideas.”

In this article, Padilla turned her critical eye towards Puerto Rico, asserting that conflict within the country was a large obstacle to obtaining independence. She argued that Puerto Rico would never be able to achieve liberation if there was disunity within the independence movement. This article illustrates how despite her ardent admiration for Puerto Rico, Padilla did not view her homeland through rose-colored glasses. Instead, she was able to recognize that Puerto Rico had to play its part in the liberation movement.

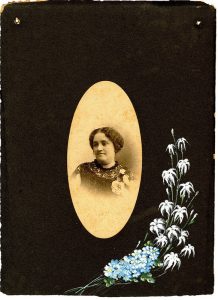

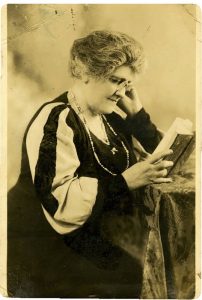

Portrait of Trina Padilla, undated.

Padilla de Sanz was a crusader for justice; she spoke for the groups often marginalized in society and implored her readers to recognize the inequalities taking place around them. She transformed her ordinary pen into a effective weapon for change, writing about various issues and identifying the problems in order to encourage progress. She was compassionate and believed that all livings things had inherent value, which stemmed from her adherence to the Catholic faith. The following works by La Hija demonstrate the various social causes she championed throughout her life.

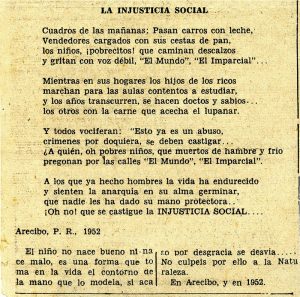

Poem by La Hija featured alongside an article published in El Día, October 25, 1952.

“La Injusticia Social”

“…nadie les ha dado su mano protectora…¡Oh no! que se castigue la INJUSTICA SOCIAL…”

Translation:

“…no one has lent them a protecting hand…Oh no! let SOCIAL INJUSTICE be punished…”

This poem illustrates La Hija’s compassion and concern for children, specifically children from disadvantaged backgrounds. She used this poem to compare how wealth inequality can lead to an endless cycle of poverty. She pointed out how children from richer families had the privilege of going to school and studying so that they can later go on to have successful careers, while children from poorer families were forced to forgo education to help support their families, making it more difficult to advance later in life. The quote above perfectly reflects Padilla’s belief that society had abandoned these innocent children by failing to provide adequate support and that it was time to alleviate their suffering by ‘punishing’ the factors that created this social injustice.

Excerpt from a speech given by La Hija at a prison in Arecibo, May 25, 1934.

“Conferencia Dada En La Cárcel De Arecibo”

“Y no vengo a recriminarles, no, vengo a endulzar esos dolores con la miel de mi palabra, con el consejo de la persuasión, con el deber que tenemos todos unos con otros, hermanos en la santa doctrina de Jesús…”

Translation:

“And I haven’t come to reproach you, no, I have come to sweeten those pains with the honey of my words, with persuasive advice, with the duty that we all have with one another, brothers in the holy doctrine of Jesus…”

This document is an excerpt taken from a speech given by La Hija in the prison in Arecibo, Puerto Rico. Padilla’s speech was filled with understanding, empathy, and an honest desire to help this ostracized group rehabilitate and reenter society. Padilla used the Catholic faith to reach out to the group, emphasizing the importance that faith plays in guiding believers back to the right path. By counseling the inmates, rather than further castigating them, La Hija demonstrated her commitment to reforming society through compassion and understanding.

Excerpt from an article written by La Hija in El Imparcial, undated.

“No Matarás”

“Qué se obtiene como ventaja al privar de la vida a un semejante?…Se regenera la sociedad con ella?…NO! La víctima queda sepultada en…la tierra y el crimen sigue floreciendo igual que si no existiera la pena de muerte”

Translation:

“What do we gain as an advantage by depriving the life of a fellow man?…Does it reform society? NO! The victim remains buried…in the earth and crime continues to flourish the same as if the death penalty didn’t exist”

In this article, La Hija strongly voiced her opinion against the death penalty as the ultimate form of punishment for criminals. She argued that taking someone’s life does not avenge the crime committed, nor does it prevent future crimes from happening. As a devout Catholic, La Hija firmly believed in the sanctity of all life and actively fought to defend this principle. This article supports La Hija’s belief in rehabilitation for society’s criminals, reflecting her compassion and willingless to help all living things.

Newspaper article written by La Hija, 1934.

“Los Viejos”

“Personalmente, el que cree hacerme una ofensa con llamarme vieja, se equivoca. Una vida tan honda, tan profundamente dedicada a lo grande, alto y noble, no puede ofenderse quien la posee porque la llamen vieja”

Translation:

“Personally, he who believes to offend by calling me old, is mistaken. A life so profound, so dedicated to the great, the high and the noble, nobody who possesses this can be offended by being called old.”

Padilla de Sanz fervently defended the elderly, noting that there was a prevalent attitude of disdain towards this segment of society. Rather than apologize for her advanced age, La Hija touted it, wearing it proudly as a badge of a long life enjoyed and filled with worthile endeavors. Writing this article on the cusp of her seventies, La Hija was a prime example of the achievements possible in old age. Her writing career would continue without pause for the next two decades.

Portrait of La Hija, undated.

When Padilla de Sanz was born in 1864, the fight for women’s rights was facing an uphill battle. Puerto Rico would not grant women the right to vote until 1929, when La Hija was well into her sixties. Throughout her lifetime, Padilla was a fervent advocate for the equality of women, believing that women were not innately inferior to men. Padilla specifically addressed-and debunked- the pervasive notion that work done by women in society was less valuable. The following documents reflect La Hija’s belief that women played a significant role in society inside and outside the domestic sphere.

Poem by La Hija, undated.

“Ana Roque De Duprey”

“Y al no poder votar aqui en su suelo,se fué a la Democracia de los astrospara dejar su voto en la urna del cielo”Translation:

“And upon not being able to vote here in her land,she went to the Democracy of the starsto leave her vote in the urn of the heavens”In this short poem written by La Hija in honor of her late friend, the suffragist Ana Roque de Duprey, Padilla de Sanz paid tribute to her friend by highlighting her achievements and noting the difficult challenges she faced in the fight for women’s suffrage. La Hija bitterly wrote that in the end, Roque de Duprey had to ascend to the heavens in order to have her vote count. In a note underneath the poem, Padilla explained that although Roque de Duprey was finally able to cast her vote in an election before her death, it was voided due to a technicality. While Roque de Duprey died thinking she had finally achieved her dream of voting, La Hija’s bitterness over the technicality and the larger struggle to obtain women’s suffrage is evident.

Excerpt from a newspaper article by La Hija, undated.

“La Mujer Ante La Guerra”

“Nunca como hoy, ha merecido la mujer el alto concepto que su nombre significa; y es porque ella…enseña al hombre con hechos, no con palabras, cómo debe considerarse como a su igual en el estado social, ya que le supera en muchos aspectos de la vida…”

Translation:

“More than ever, women deserve the esteemed notion that her reputation conveys; and it’s because women…teach men with actions, not with words, how they must consider women their equal in the social state, since women surpass them in many aspects of life…”

In this excerpt, La Hija extolled the vital role that women play in war, highlighting their role serving for the Red Cross and entering the most dangerous war zones. She made it clear that although women and men had different roles in the war effort, the jobs performed by the women were equally as important. As the quote above demonstrates, La Hija believed that women had unequivocally proven their equal status with men.

Excerpt from newspaper article by La Hija, 1938.

“Las Mujeres No Contamos”

“La eterna canción de que el cerebro de la mujer está formado en condiciones muy inferiores al de los hombres, está descartado hace tiempo…”

Translation:

“The eternal song that the brain of the woman is formed in conditions inferior to that of a man, was refuted a long time ago…”

La Hija addressed a pattern she saw in the press saying how women have not contributed to the advancement of civilization. She pointed out various accomplished women in history to demonstrate that women are not innately inferior to men. Rather, not only do they have their own accomplishments, but also they played a role in the achievements of men by raising them and instilling proper values and work ethic.

Excerpt of an article by La Hija in La Patria, August 22, 1914.

“La Labor De Las Madres En El Hogar”

“Sí, porque los hogares son el corazón de la patria… se nutren los pueblos. La labor que la madre portorriqeña puede realizar en bien del terruno es insuperable.”

Translation:

“Yes, because the homes are the heart of the homeland…they nourish nations. The work that the Puerto Rican mother can carry out for the sake of the homeland is unsurpassable.”

La Hija wrote about the crucial role that mothers play in instilling morals in their children, therefore playing a huge role in their successes. She mentioned important and powerful figures like George Washington and Alfonso XIII to show how their mothers influenced their achievements. Specifically, Padilla de Sanz identified the belief that the work done in the private sphere is seen as inferior to the work done in the public sphere. She contested this belief by explaining how crucial the work done by women in the home helps support the nation.