CELEBRATING JUNETEENTH

Juneteenth commemorates June 19, 1865, the day federal troops led by General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas to inform Texans that all enslaved people were now free. Their arrival came two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, which freed all enslaved people in Confederate states. Slavery continued in Texas during the Civil War since there was not any large-scale fighting as well as a lack of Union troops. Many slave owners even moved to Texas during that time.[1] Upon General Granger’s arrival in Galveston, there were 250,000 enslaved people in Texas.[2] Slavery was formally abolished in the United States with the ratification of the 13th Amendment in December 1865. Juneteenth, a combination of “June” and “19th,” is the oldest known celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the United States.[3] While Juneteenth celebrations originated in Texas, which was also the first state to make it an official holiday, 47 states and Washington D.C. recognize it as a state holiday today and there is a push to make it a federal holiday as well.

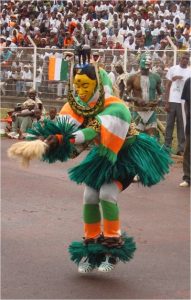

In recognition of Juneteenth, the Walsh Gallery has created a teaching collection from a subset of the Seton Hall Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology Collection (SHUMAA). It is a vast collection of art and artifacts compiled by former Seton Hall Professor Herbert Kraft from a variety of world cultures. This collection in particular consists of sculptures and masks from places such as Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Nigeria, and Ghana in addition to many other countries and cultures. The statue featured above is a Benin courtier serving as an emissary to the Oba, or king, of Benin from the Ooni of Ife, the monarch of the Yoruba people. The original sculpture was cast in bronze. The Kingdom of Benin (which is different from the present-day nation state of the same name), also known as the Edo Kingdom or the Benin Empire, existed from around the 11th century CE until 1897. The kingdom was located in West Africa in what is now Nigeria. This statue, along with two other pieces from the collection, are currently on view in the window display in the Walsh Library Rotunda on the second floor. Make sure to take a look! Materials in the Teaching Collection can be utilized by students and faculty for research projects and classroom learning for object-based projects. To check out these objects, contact the Walsh Gallery at walshgallery@shu.edu or by phone at 973-275-2033.

[1] https://www.history.com/news/what-is-juneteenth, accessed 6/11/21.

[2] https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/historical-legacy-juneteenth, accessed 6/11/21.

[3] https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/juneteenth-original-document, accessed 6/11/21.