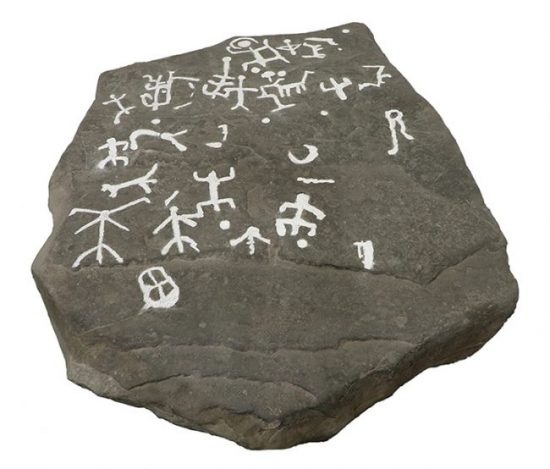

Jennings Petroglyph

sandstone

5’ x 4’ x 9.5”

3000-1000 BCE

FIM 610

Seton Hall University Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology

NOVEMBER IS NATIONAL NATIVE AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH

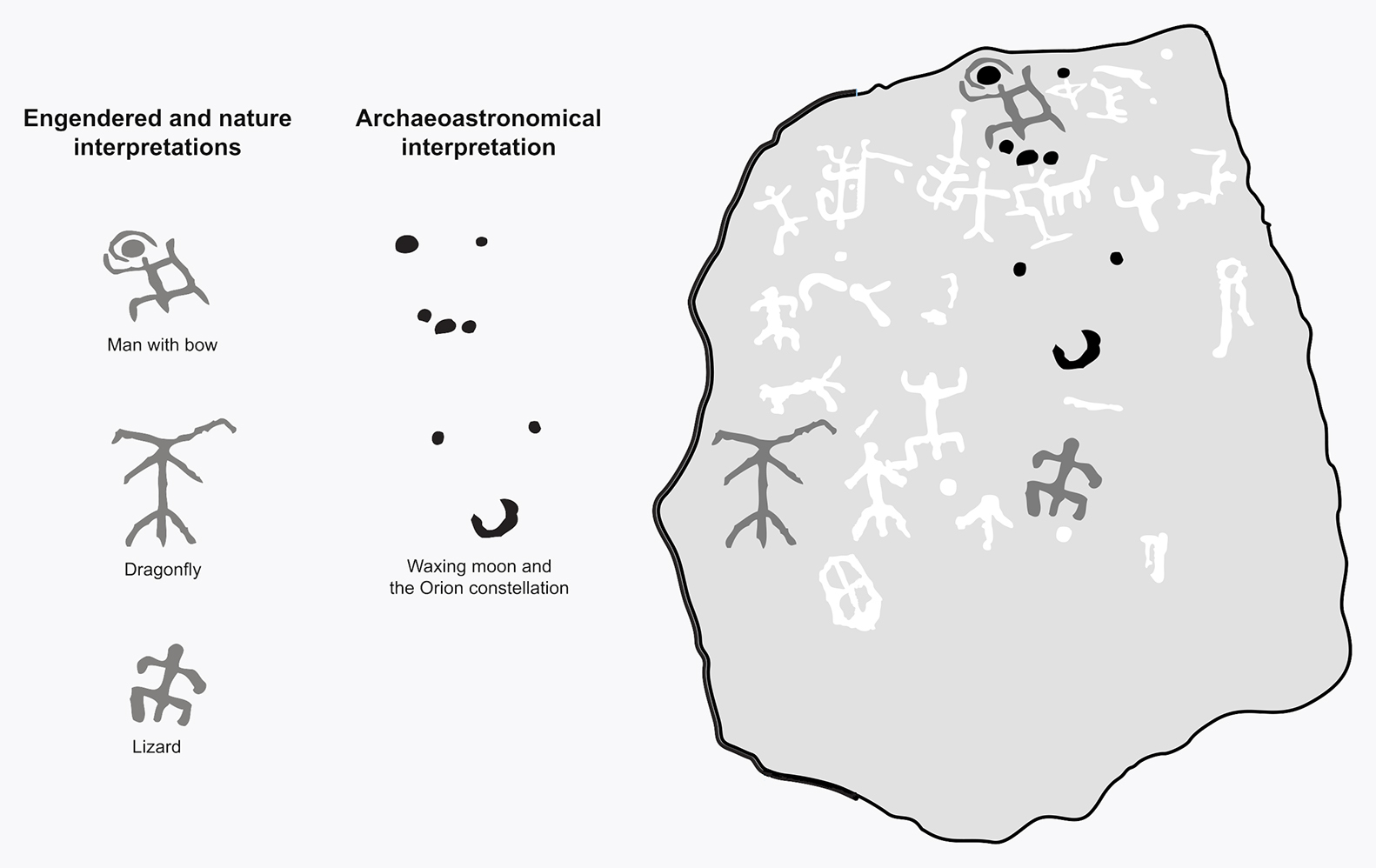

The Jennings Petroglyph, an uncommon example and one of the largest of its kind in New Jersey, was created between 1,000 and 5,000 years ago. It was originally located on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River across from Dingmans Ferry in Pike County, Pennsylvania. Meaning “rock carving,” the word petroglyph combines “petro” meaning “rock” and “glyph” meaning “symbol.” The exact significance of the imagery on the petroglyph has been obscured over time, though it is believed to likely be sacred. The petroglyph’s surface features 21 identifiable figures and 12 non-identifiable forms – including carvings of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures as well as dots and circles (cupules). Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Seton Hall, Herbert Kraft (1927-2000), described the images as “lizard-like figures or men with sexual appendages.”[1]

The petroglyph was unearthed by Rudyard Jennings in 1965. It was donated to Seton Hall with the intention of protecting it from flooding caused by the proposed Tocks Island dam on the Delaware River site where the petroglyph was previously located. Ultimately, the dam was never built. The petroglyph’s first home at Seton Hall University was in the lobby of Fahy Hall, but it was moved to the second floor of the Walsh Library in August 2015. This move has allowed for easy viewing access by the university community and the public.

The Jennings Petroglyph will be featured in an exhibit at the National Scenic Visitors Center (NSVC) in Zionsville, Pennsylvania. The NSVC, founded in 2016, has the ultimate 10-year goal of creating Earthwalk USA, a 300-foot-long, 3D relief map of the United States from California to Maine, along with Alaska and Hawaii in correct geospatial orientation.[2] In the meantime, they have planned a traveling exhibit called Earthwalk Explorer featuring a 16’ x 8’ walkable relief map of the Northeast along with two Geoshows. In both Earthwalk USA and the traveling show, visitors will walk over the relief map in socks so that they can feel the topography of the United States for themselves! Our very own Jennings Petroglyph will be highlighted in one of the Geoshows, which centers on petroglyphs in Pennsylvania and how native groups of the region used them to communicate along trails. In early 2020, Michael Bianco of MZB Productions, Inc. came to Seton Hall to make a high-resolution scan of the petroglyph in-situ in order to create a 3D facsimile.

The Jennings Petroglyph is part of the Seton Hall University Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology (SHUMAA) collection. It is but a small part of a vast collection of artifacts from the SHUMAA collection, founded by Seton Hall Professor Herbert Kraft (1927-2000), a leading archaeologist and authority on the Leni Lenape tribe which inhabited New Jersey, Delaware, southern New York and eastern Pennsylvania at the time Europeans arrived in the Americas. For almost forty years, Kraft cultivated the collection with artifacts excavated from archaeological digs conducted throughout the region. Kraft was also instrumental in securing donations of artifacts from noted collectors and archaeologists. The SHUMAA collection includes over 26,000 Native American, Asian and African art and artifacts.

The Walsh Gallery has a considerable collection of fine art, artifacts and archeological specimens for use by faculty, students and researchers. For access to this or other objects in our collections, contact us at 973-275-2033 or walshgallery@shu.edu to make a research appointment.

[1] https://library.shu.edu/ld.php?content_id=51066456, accessed 11/23/2020.

[2] https://www.nsvc.us/exhibits-features/earthwalk-usa-map/, accessed 11/23/2020.