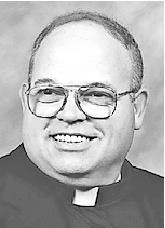

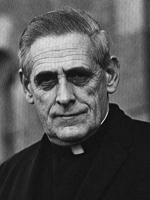

Monsignor John A. Stafford, S.T.L., was the eighth President of Seton Hall College from 1899 to 1907, presiding over the college’s Golden Anniversary in 1906. At the dawn of the new century, Monsignor Stafford oversaw a number of advances on our campus including the construction of a School Infirmary and a residence for the Sisters of Charity, which helped run campus operations at the time.[i] The order was founded in the tradition of Seton Hall University’s namesake, Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, and the sisterhood, which still operates today from Convent Station in Morris County, New Jersey, advocates for human rights, peace and non-violence, while promoting systemic change. In addition to putting his support behind health and humanitarian causes, Monsignor Stafford’s tenure also saw the first inter-collegiate basketball team in 1903 and inaugurated the construction of the college’s first permanent baseball diamond just two years later.[ii]

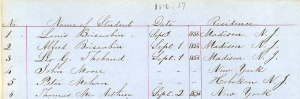

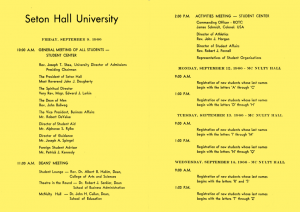

Monsignor John A. Stafford studied classics at St. John’s in Pennsylvania and later, at Seton Hall College. He continued his studies at the seminary at Pontifical North American College in Rome in 1882. Six years later, he was ordained and entered the priesthood on April 8, 1888. On returning to the United States, he served in various New Jersey parishes and was later appointed as Vice President of Seton Hall College in 1893 under Father Marshall’s administration. In 1897 he was selected as rector of St. Augustine’s Church in Union Hill (Union City), New Jersey before returning to Seton Hall College in 1899 to serve as President after being appointed on May 10, 1899 by the Most Rev. Winand M. Wigger, third Bishop of Newark.[iii] At the time, student enrollment at the college was 165. In comparison, today’s enrollment is well over 10,000 students.[iv]

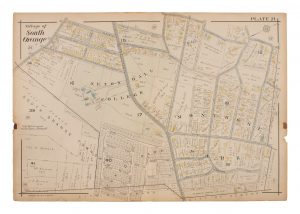

In Monsignor Stafford’s time, the campus of Seton Hall College was very different. South Orange was still a rural area with many farms and open spaces. In fact, there was a farm on the north side of South Orange Avenue which contained a dairy to supply food products needed on campus. Students and professors were obligated to obey the rule of silence which forbade talking in any of the class corridors. Saturday was no time for resting – students attended a full day of classes on that day too. There was a less stringent side to Monsignor Stafford who was known to have a good singing voice. There are accounts of him regaling students and faculty at a Christmas party to his renditions of “Noel,” followed by an encore of “An Old Christmas Dinner.”[v]

In addition to serving as the President of Seton Hall College, Monsignor Stafford was simultaneously charged with running the seminary rectory. Monsignor Stafford, despite his busy schedule, frequently lectured in pastoral theology and liturgy. During his term as President, a liberal arts curriculum was emphasized with “stress on the classics, history, English, mathematics, philosophy, and systematic instruction in the Catholic religion.” [vi] During his tenure as President of Seton Hall College, Father Stafford was elevated to the rank of Monsignor in 1903.

The Golden Jubilee celebrations in 1906 in which Monsignor Stafford presided were filled with commemorative ceremonies and special events, including the very first commencement exercises held indoors at the nearby H.C. Miner’s Newark Theatre, which opened in 1886 as a vaudeville house. With its elaborately decorated interior and grand façade, the theatre was an elegant setting for the graduation ceremonies. [vii] Though its name has since changed many times and the current marquee shows its age, the old theatre still stands prominently at 195 Market Street, just steps from Seton Hall Law School in the city’s downtown business district.

Citing health issues, Monsignor Stafford resigned in 1907 and was succeeded by Monsignor John F. Mooney as President.[viii] Monsignor Stafford continued to serve the community after leaving Seton Hall College, becoming pastor of St. Paul of the Cross Church in Jersey City, New Jersey. He then went to St. Patrick’s Church in Jersey City. He died on January 21, 1913, not far from his native Paterson, New Jersey where he was born on March 13, 1857.[ix]

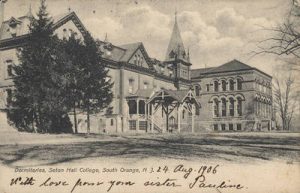

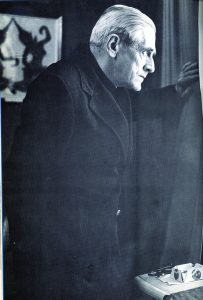

Monsignor Stafford’s influence can still be felt on campus today. The portrait of Monsignor Stafford painted by A. Dies in 1904, watches over activities in President’s Hall. The liberal arts curriculum he favored is still taught, now joined by additional courses of study in the sciences, medicine, business and diplomacy, among others. Stafford Hall, one of three original buildings, was one of the centerpieces of the campus at the time of its completion. Originally used as a dormitory, Stafford Hall was rebuilt in 2014 on its same location between Marshall Hall and the Immaculate Conception Seminary and School of Theology. The new building is constructed in the original neo-gothic style, but offers 21st century amenities to accommodate student and faculty needs. This building style, drawing from the past, but equipped to support student achievement, is a metaphor for Monsignor Stafford’s leadership and service in the Catholic tradition – rooted in a rich past, while striving towards potentiality.

For r access to this painting or other materials from our collections featured in previous Object of the week posts, fill out this research request form to set up a research appointment.

[i] https://www.shu.edu/president/presidents-of-seton-hall.cfm, accessed 9/21/2020

[ii] https://www.shu.edu/president/presidents-of-seton-hall.cfm, accessed 9/22/2020

[iii].https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/digitallibrary/smof/publicliaison/blackwell/box-034/40_047_7007844_034_008_2017.pdf, accessed 9/23/2020

[iv] https://archivesspace-library.shu.edu/repositories/2/resources/277, accessed 9/23/2020

[v] https://www.shu.edu/president/presidents-of-seton-hall.cfm

[vi] https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/digitallibrary/smof/publicliaison/blackwell/box-034/40_047_7007844_034_008_2017.pdf , accessed 9/23/2020

[vii] https://afterthefinalcurtain.net/2011/09/28/the-newark-paramount-theatre/#:~:text=The%20Paramount%20Theatre%20opened%20on,Brooklyn%20based%20theater%20Management%20Company, accessed 9/22/2020

[viii] Flynn, Joseph M. The Catholic Church in New Jersey. Morristown, NJ: 1904. Kennely, Edward F. A Historical Study of Seton Hall College. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, 1944.

[ix] https://archivesspace-library.shu.edu/repositories/2/resources/277 9/23/2020

Additional postings regarding the life and legacy of Monsignor Fahy will be forthcoming. In the meantime, please feel to contact us if you need further information on Monsignor Fahy and all aspects of Seton Hall University. We can be reached via e-mail at:

Additional postings regarding the life and legacy of Monsignor Fahy will be forthcoming. In the meantime, please feel to contact us if you need further information on Monsignor Fahy and all aspects of Seton Hall University. We can be reached via e-mail at: