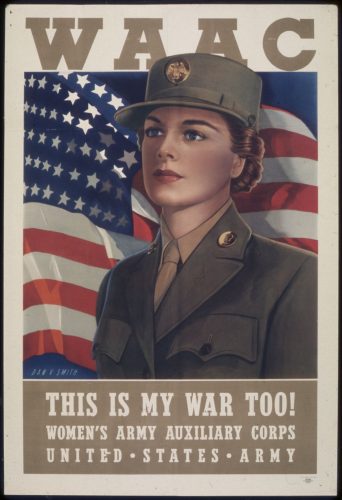

On March 17, the House of Representatives passed a highly controversial bill that created the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). The WAAC is a volunteer organization that would allow the nation’s women to serve with the armed forces in non-combatant military duties.

The women of WAAC will be the first ever women other than nurses to serve within the ranks of the U.S. Army. From Wikimedia Commons.

The bill, which was proposed by Representative Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts, was passed with two amendments that limited the corps to 150,000 women and permitted Army and Navy nurses to volunteer.

The WAAC is seeking female volunteers between 18 and 65 years old to participate in the war effort. These women would volunteer in all nine corps of the army.

No names have yet been released as to who will be director of the 150,000 volunteer women, but it was admitted by government officials that “real and tough army officers” will lead the WAAC.

However, prominent women in the war effort have been rumored to play important roles in leading the WAAC. Iveta Culp Hobby, chief of the women’s interest division, and Mrs. William Gutwillig, who is in charge of the 800 women volunteers in the New York Auxiliary Aircraft Warning Service, may both be enlisted to help lead the WAAC volunteers.

Although this bill would free up enlisted men who are performing duties behind the lines and allow them to engage in actual combat, many members of the House have opposed it.

Rep. Clare Hoffman, a Republican from Michigan said that the women of the United States who “sew on the buttons, do the cooking, mend the clothing and do the washing at home,” don’t actually want to enlist and want to remain at home.

“I venture to suggest that if we could get a secret expression or vote on this bill, members of the House would turn the bill down today or at any other time it came up,” Hoffman said. “Because, after all, are you going to send these women away from homes where they can render service or away from factories where they may be needed?”

Some Democrats opposed the bill too, including Rep. Jennings Randolph of West Virginia, who called the bill “foreign” to American values, and Rep. Butler B. Hare of South Carolina, who said it reflected terribly on the nation’s men, suggested that they now need women to do their work for them.

The House discussion on the bill, which lasted approximately four hours, was spent mostly deciding how army law would apply to the women in the corps.

It was voted that if any of the WAAC volunteers were to disobey orders or act out, the only disciplinary action the War Department would have over the volunteer is discharge without honor, which Rep. Rogers felt was sufficient.

Rep. John Conover Nichols of Oklahoma proposed an amendment to the bill that would have entitled members of the WAAC to receive the same compensation, pensions and disability benefits that are available to soldiers.

The amendment was rejected, despite Nichols contesting that the women would be serving “in the field” with men during the war.

For the time being, training facilities are being set up for the volunteers, who can be sent off to serve in any part of the world where they are needed. The War Department stated that the first 12,500 volunteers will be used in aircraft watching and filter centers. Other roles that these women may fulfill include telephone operators, clerks, stenographers, secretaries and laundry workers.

Sources:

NONA BALDWIN. (1942, Mar 18). “Bill for women’s auxiliary corps of 150,000 passed by the house.” New York Times. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/106137844?accountid=13793

Christine Sadler. (1942, Mar 19). “House bill asks registration of women 18-65.” The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/151492974?accountid=13793

By Christine Sadler. (1942, Mar 18). “House votes women’s corps of 150,000.” The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/151566639?accountid=13793

So interesting in how new political system integrates women around duties and activities that serve the world becoming volunteers of love. Women is not only a fashion tool.