One of the most common reasons for manuscript rejection is submitting to an unsuitable journal. Start your publication journey by choosing the right journal for your manuscript and you’ll improve your chances of acceptance and publication.

Having a preferred journal in mind will help you align your writing to meet the journal’s aims and scope. Below are some tools and resources that will help you to find the right journal to publish in.

| Tool Name |

Link |

|

Journal/Article Name Estimator |

https://jane.biosemantics.org/

Just enter the title and/or abstract of the paper in the box, and click on ‘Find journals’, ‘Find authors’, or ‘Find Articles’. Jane will then compare your document to millions of documents in PubMed to find the best matching journals, authors, or articles. |

|

Scopus Journal Comparison |

https://www.scopus.com/source/eval.uri

Scopus metrics help measure the impact of scholarly research, including the h-index, citations, and journal metrics such as the CiteScore, SNIP and SJR. Allows you to compare 10 journals at once. |

|

Jot: Journal Targeter |

https://jot.publichealth.yale.edu/

Jot is a web app, hosted by Yale School of Public Health, that identifies potential target journals for a manuscript, based on the manuscript’s title, abstract, and (optionally) references. Jot gathers a wealth of data on journal quality, impact, fit, and open access options that can be explored through linked, interactive visualizations |

|

Springer Journal Suggester |

https://link.springer.com/search?facet-content-type=%22Journal%22

Publisher Springer’s journal matching technology finds relevant journals based on your manuscript details. You can search over 2.500 journals (all Springer and BMC journals) to find the most suitable journal for your manuscripts. |

|

Elsevier Journal Finder |

https://journalfinder.elsevier.com/

Publisher Elsevier® JournalFinder helps you find journals that could be best suited for publishing your scientific article. Simply insert your title and abstract and select the appropriate field of research for the best results. |

|

Taylor & Francis Journal Suggester |

https://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/publishing-your-research/choosing-a-journal/journal-suggester/

Publisher Taylor and Francis Author support services helping you find the best journal |

|

SPI-HUB |

https://spi-hub.app.vumc.org/

The SPI Hub: Scholarly Publishing Information Hub is authored and managed by the Center for Knowledge Management at Vanderbilt University Medical center. |

|

Think. Check. Submit |

https://thinkchecksubmit.org/journals/

Think. Check. Submit helps researchers identify trusted journals and publishers for their research. |

|

Wiley Journal Finder |

https://journalfinder.wiley.com/search?type=match

Publisher Journal Finder can suggest Wiley journals that may be relevant for your research. You can simply enter your title and abstract to see a list of potential journals. |

|

SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) |

https://www.scimagojr.com/

The SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) indicator is a measure of the scientific influence of scholarly journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where the citations come from. |

|

DOAJ – Directory of Open Access Journals |

https://doaj.org/

DOAJ contains almost 17.500 peer-reviewed, open access journals covering all areas of science, technology, medicine, social sciences, arts, and humanities. If you are looking only for open access journals, there are also ways of searching for these by filtering your search results through journal comparison tools. |

|

Sage Journal Recommender |

https://journal-recommender.sagepub.com/

Publisher Find relevant journals for your manuscript, verify against aims & scope, and submit to one directly or use Sage Path. |

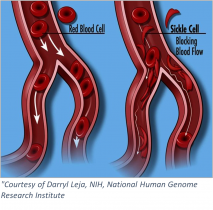

Sickle cell anemia is an inherited blood-borne disease affecting some 100,000 individuals in the US, and nearly 8 million worldwide. Persons of sub-Saharan African descent appear to manifest the disease to the greatest extent, with those of Indian, Hispanic, or Middle Eastern backgrounds also highly affected. The pathology is devastating – misshapen red blood cells occlude blood vessels, compromising flow and inhibiting oxygen delivery. Pain develops frequently in oxygen-deprived tissues. Other complications include an enhanced susceptibility to infections, various eye problems, organ damage, and increased risks of pulmonary/heart disease and stroke.

Sickle cell anemia is an inherited blood-borne disease affecting some 100,000 individuals in the US, and nearly 8 million worldwide. Persons of sub-Saharan African descent appear to manifest the disease to the greatest extent, with those of Indian, Hispanic, or Middle Eastern backgrounds also highly affected. The pathology is devastating – misshapen red blood cells occlude blood vessels, compromising flow and inhibiting oxygen delivery. Pain develops frequently in oxygen-deprived tissues. Other complications include an enhanced susceptibility to infections, various eye problems, organ damage, and increased risks of pulmonary/heart disease and stroke.