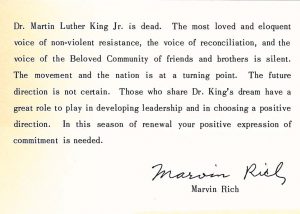

Civil Defense Medical Corp Armband

embroidered textile

mid-20th century

Leonard Dreyfuss papers

MSS 0001

Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections

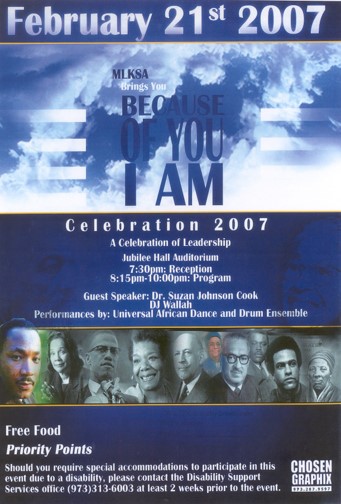

JANUARY IS NATIONAL BLOOD DONOR MONTH

First observed in January 1970, National Blood Donor Month brings attention to the heightened need for blood and platelet donations in the winter months, typically the most difficult time of the year to meet

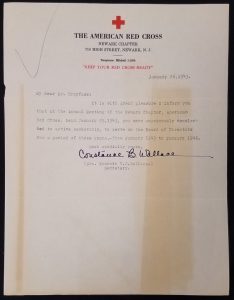

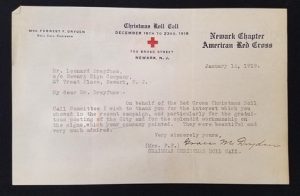

The American Red Cross – Newark Chapter

January 26, 1943

Leonard Dreyfuss papers (MSS 0001)

Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections

patients’ needs for these products. Inclement weather and the onset of flu season shrinks the donor pool while demand increases.[1] Though COVID-19 has altered our daily lives, hospitals and clinics still serve patients in need of blood transfusions. COVID-19 has forced many health care facilities to serve patients at a different capacity by temporarily closing clinics and suspending elective services and procedures or shifting to virtual care in many cases. Yet the need for blood still exists to perform transfusions in most emergent cases, such as traumas, cancer patients, orthopedic surgeries, and many others. Unfortunately, while the need for blood is growing, fewer people are donating presently.[2]

Did you know that one in seven hospital patients will use blood? Or that one in 83 births will require a blood transfusion? If you know someone who has cancer, is pregnant, or has sickle-cell disease, then you might know someone who may need blood. On December 31, 1969 President Richard Nixon proclaimed January 1970 as the first official observance of National Blood Donor Month as requested by Senate Joint Resolution 154, to

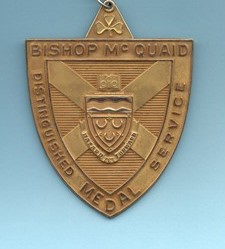

1943

Leonard Dreyfuss Papers (MSS 0001)

Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections

pay tribute to voluntary blood donors and encourage new donors.[3] The American Red Cross provides roughly 35% of donated blood in the United States, while community-based organizations provide 60% and the remaining 5% of the blood supply is collected directly by hospitals.[4] The American Red Cross was founded in Dansville, New York in 1881 by Clara Barton, who served as a nurse during the American Civil War.[5]

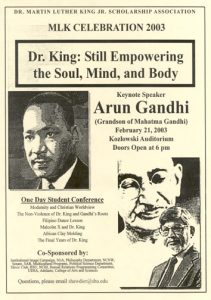

These objects are from the Leonard Dreyfuss Collection on deposit at the university’s Archives and Special Collections. Leonard Dreyfuss served as Chair of the Newark Chapter of the American Red Cross from 1956 to 1960, and was distinguished as an honorary director of the of the chapter for life.[6] He also volunteered for the New Jersey Civil Defense which was formed by legislation in 1942 “to provide for the health, safety and welfare of the people of the State of New Jersey and to aid in the prevention of damage to and the destruction of property during any emergency.”[7] Dreyfuss also served as a trustee of the Newark Museum and the advisory board at Seton Hall University, which awarded him an honorary degree in 1950. Leonard Dreyfuss was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 6, 1886. In 1914, he joined the Newark Sign Company – an outdoor sign

American Red Cross – Newark Chapter

January 12, 1919

Leonard Dreyfuss papers (MSS 0001)

Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections

advertising firm. After 1923, he led a highly successful merger with several advertising companies which became known as U.A.C. Dreyfuss rapidly moved up the executive ladder, becoming Vice President, President and finally, Chairman of the Board before retiring in 1965. Leonard Dreyfuss died on December 29, 1969 in Essex Fells, New Jersey. [8]

The Leonard Dreyfus Papers show the namesake’s commitment to service, particularly his efforts with the Civil Defense and Newark Chapter of the American Red Cross. These materials are available to students, faculty and researchers. For access, set up a research appointment online or contact us at 973-761-9476.

[1] https://www.few.org/national-blood-donor-month/ accessed 1/12/2021

[2] https://news.llu.edu/patient-care/why-giving-blood-necessary-during-pandemic accessed 1/12/2021

[3] https://www.adrp.org/NBDM accessed 1/12/2021 accessed 1/12/2021

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Red_Cross#Blood_donation, accessed 1/12/2021.

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clara_Barton, accessed 01/12/2021.

[6] https://archivesspace-library.shu.edu/repositories/2/resources/168, accessed 01/12/2021.

[7] http://ready.nj.gov/laws-directives/appendix-a.shtml, accessed 01/12/2021.

[8] https://archivesspace-library.shu.edu/repositories/2/resources/168, accessed 01/12/2021.