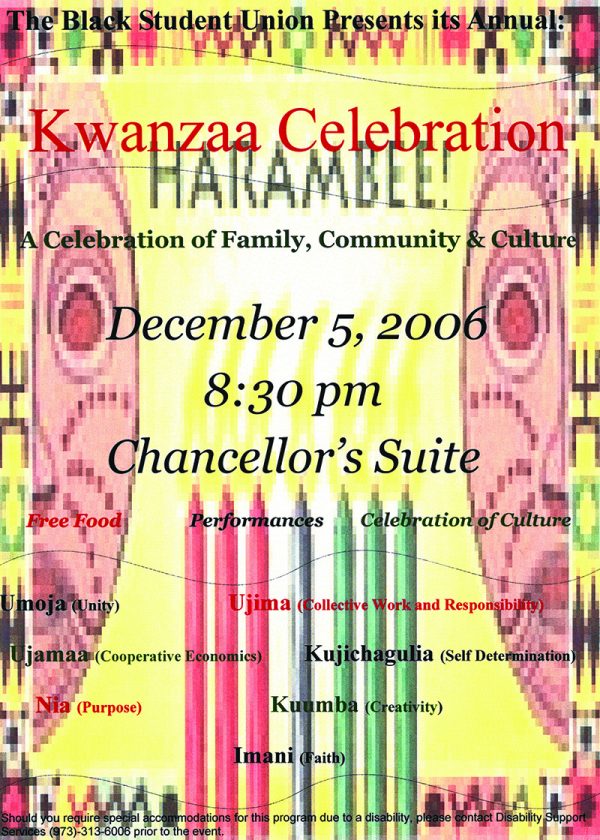

“Kwanzaa Celebration Invitation”

2006

Black Student Union vertical file

Seton Hall University Archives and Special Collections

HABARI GANI

Kwanzaa is a seven-day celebration of African American culture observed annually from December 26 through January 1. During Kwanzaa, it is customary to greet friends and family with the phrase, “Habari gani,” meaning, “What is the news?”[1] In response, one can reply with one of the seven different principles assigned to each day. Every evening during Kwanzaa, a candle is lit on the kinara, or traditional candleholder, to honor the seven principles:

-

- Umoja (Unity)

- Kujichagulia (Self-determination)

- Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility)

- Ujamaa (Cooperative economics)

- Nia (Purpose)

- Kuumba (Creativity)

- Imani (Faith)

Tech. Sgt. Jennifer Myers (above), 66th Air Base Wing noncommissioned officer in charge of the Military Equal Opportunity office, lights a candle in the Kinara. photo by Christopher Myers, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

These seven tenets of Kwanzaa, or Nguzo Saba, are collectively referred to as Kawaida, a Swahili word meaning “common.”[2] The candles used in the kinara are red, green and black – each color having a different attribute. The three red candles on the left of the kinara signify the blood shed in the fight for liberation, three green candles on the right stand for the future of Black liberation and the single black candle in the center symbolizes the people this celebration honors.[3]

Kwanzaa was first celebrated in 1966 when Maulana Karenga, a college professor of Africana studies at California State University in Long Beach, created the holiday to honor and celebrate pan-African culture. Karenga said his goal was to “give Blacks an opportunity to celebrate themselves and their history, rather than simply imitate the practice of the dominant society.”[4] At the time Karenga conceived of Kwanzaa, Los Angeles was reeling in the aftermath of the Watts Rebellion which devasted the south Los Angeles neighborhood in August 1965 after a traffic stop resulted in the arrest of a 21-year-old African American man, Marquette Frye. For the next six days, violence and civil unrest rocked 46 square miles of Los Angeles.[5] It was against this political backdrop that Karenga sought to create a positive force for African Americans and African American culture.[6] According to Karenga, Kwanzaa was partly inspired by the Zulu harvest festival, Umkhosi Wokweshwama, a five-day lunar ritual that takes place during the last full moon of the year.[7]

The name Kwanzaa is taken from the Swahili phrase “matunda ya kwanza,” meaning first fruits. The extra “a” was added, said Karenga, to make the word Kwanzaa seven letters to enhance its symbolic power.[8] Kwanzaa is a cultural event imbued with spiritual values, but it is not a religious observance. People of all faiths may celebrate Kwanzaa and non-blacks can also observe the holiday.[9] On his official Kwanzaa website, Dr. Karenga notes, “The holiday, then will of necessity, be engaged as an ancient and living cultural tradition which reflects the best of African thought and practice in its reaffirmation of the dignity of the human person in community and culture, the well-being of family and community, the integrity of the environment and our kinship with it, and the rich resource and meaning of a people’s culture.”[10]

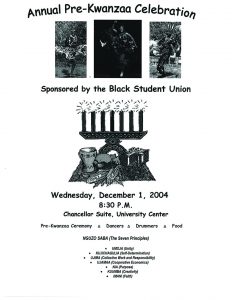

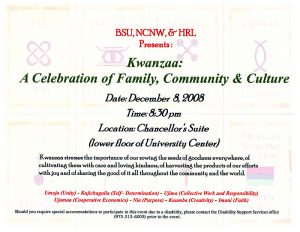

The Department of Archives and Special Collections maintains vertical files of documents and materials related to African American Studies, Black Studies, African American Alumni Association/Council, African American Heritage Month, African American Students Association, Africana Studies, African Student Association, Black History Month, Women of Hope, Black Studies Center, Institute in Afro-American History and Culture, Rallies, and University of Sierra Leone Summer School. The images accompanying this blog post show Annual Kwanzaa celebrations organized by the Black Student Union at Seton Hall University, part of this large collection of materials preserved by the university’s archives. These materials are available to students, faculty and researchers. For access, complete a research request form to set up an appointment or contact us at 973-761-9476.

[1] http://anacostia.si.edu/exhibits/past_exhibtions/kwanzaa/kwanz.htm, accessed 12/15/2020.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwanzaa, accessed 12/15/2020.

[3] https://www.womansday.com/life/a33663207/when-is-kwanzaa/, accessed 12/15/2020.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwanzaa#cite_note-5, accessed 12/15/2020.

[5] https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/frye-marquette-1944-1986/, accessed 12/15/2020.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watts_riots, accessed 12/15/2020.

[7] https://www.zululandnews.co.za/project/zulu-first-fruits-cultural-festival-umkhosi-woselwa/, accessed 12/15/2020.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwanzaa#cite_note-5, accessed 12/15/2020.

[9] https://www.history.com/news/5-things-you-may-not-know-about-kwanzaa, accessed 12/15/2020.

[10] https://www.officialkwanzaawebsite.org/, accessed 12/15/2020.