Signed, Sealed, Inspected

Opening letters that were meant for someone else’s eyes only. That’s what Frieda Finklestein Feller does as a deputy assistant censor at the New York branch of the Censorship Office. Her goal is to protect American troops abroad, and to keep war-zone strategies and plans from foreign enemies.

A 1941 graduate from Douglass Residential College of Rutgers University, Feller began her job at the New York Censorship Office in January 1942. She applied for a Federal Civil Service position as a translator while still at college and passed written tests for French and Spanish.

Feller started working for the Censorship Office about five weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The attack that changed American life, as she knew it— as all Americans knew it.

“It was right at the beginning, and Censorship didn’t have that many people. They were setting it up fast,” Feller said. An essential part of her job is being able to interpret and understand languages other than English due to the diversity of the influx of letters that came in.

During her shifts sitting at long tables, Feller has “little wooden blocks,” two cards that read French and Spanish to go along with the corresponding letters that have to remain at her desk at all times.

“They never give me the Portuguese one,” Feller said. “We are never, never, ever to reveal anything that happens. Certainly, not the methods.”

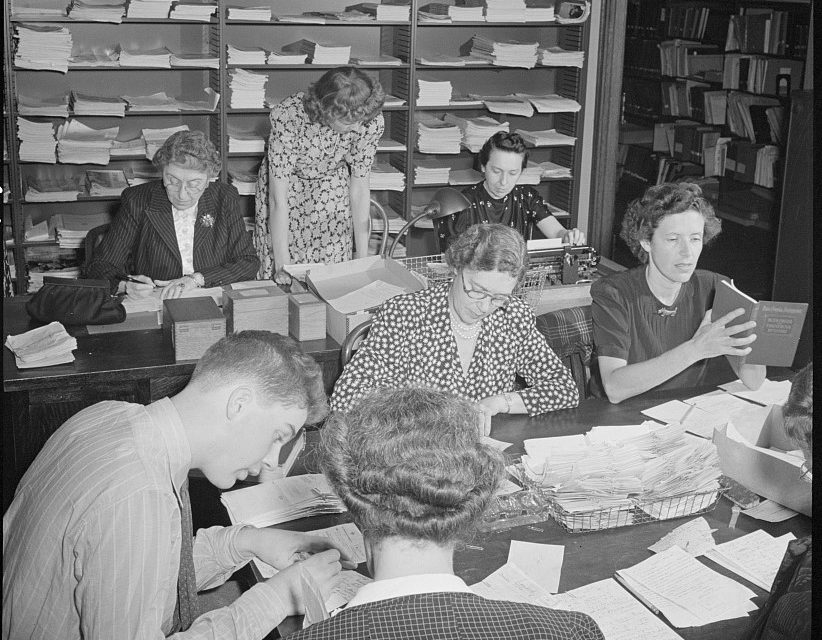

Volunteers translate messages from foreign countries before sending them to the Censorship Office. Photograph by Marjory Collins, from Library of Congress.

Understanding the madness behind the method

Feller’s office is one of several branch offices that report to the main Office of Censorship, headquartered in Washington, D.C. According to Feller, all mail leaving the country is “read and examined carefully for any information that could endanger our citizens or be of benefit to our opponents,” she said.

The departments to review the mail were set up to handle personal, business, and army mail.

Feller said that workers went to their jobs six days a week at first, and then worked five and a half days per week once more employees were hired. The workers were dedicated to their jobs to be in full support of the war effort, and to make every attempt they could to prevent harm from American troops.

“We are all afraid to miss a day because there is a chance that we might miss a letter and some catastrophe to our troops might be a consequence,” Feller said. “We are trained to know what information should be kept inside the country. Words, phrases or products, which could be of use to or give comfort to the enemy. That information is excised literally with a razor blade.”

Feller sometimes reads tragic stories when she opens mail as a censor.

“Break your heart. You just remember the ones you want to remember. Some of them are horrendous in the way people live,” Feller said about some of the letters. “You have to be grateful even though we didn’t have money.”

Razor sharp censoring prevents wounds abroad

Feller said that the methods of the censorship office served well since the leads from spies caught in war started in a censorship office. “We are very concerned about secrecy. We had to sign a paper indicating that we will never tell any of the rules, regulations or techniques found,” Feller said.

Explaining the rules and techniques of her job, Feller explains what she must do on a daily basis when examining letters.

Feller searches through mounds of letters every day. She prevents unauthorized letters from being sent abroad and she and her colleagues read every letter that comes in.

“Anything about where any troops are, anybody leaving from any port, expected in from any port, anything about a convoy,” Feller explained about what she had to look out for. “That is really hard and we have lights, long electric bulbs, and we put them inside the envelope.”

The censors also make extensive use of microfiche, small sheets of film that contain micro-photographs of a document’s pages.

Supporting the war efforts in more way than one

The responsibilities of her job weight heavily on Feller. If she fails to censor some bit of sensitive information, that could result in American servicemen dying. “God forbid, it was somebody’s brother or somebody’s husband or somebody’s nephew. It was on your conscience that you went home and you missed the letter.”

Feller’s husband, Robert Feller, is currently deployed overseas. They married six months before his departure, and he tries to write her every day so that she knows he is alive and well.

Feller recalled that there was already a gas rationing when they went on their honeymoon, so they took the train instead to Lake George, N.Y.

Feller is the embodiment of supporting the war both at work and at home.

Editor’s Note: Some quotations from Feller have been changed from past tense to present tense.

Source:

Rutgers Oral History, “Frieda Finklestein Feller.” Interviewed by Kurt Piehler & Elizabeth Wyatt. Available at http://oralhistory.rutgers.edu/social-and-cultural-history/30-interviewees/interview-html-text/604-feller-frieda-finklestein.