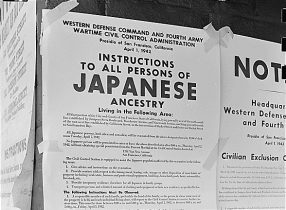

Exclusion Orders posted on walls telling Japanese Americans in San Francisco to evacuate. From Wikimedia Commons.

Several months after President Roosevelt’s order stating that Japanese-Americans who live on the West Coast must move inland, the War Relocation Authority (WRA) has halted voluntary resettlement efforts until further notice.

Although some have raised concerns about the civil liberties of those being forced to leave their homes, those concerns are not responsible for the moratorium on relocations. The problem, rather, is that many communities where evacuees are being resettled do not want to take them in.

State and local governments in Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas have lodged protests, citing various reasons. Colorado governor Ralph L. Carr, expressed concern about public safety, stating that the arrival of Japanese-Americans might “create an emotional explosion” that would endanger the evacuees.

Mayor L. L. Williamson, of Greeley, Colo., has opposed the planned resettlement of 75 Japanese-Americans in his city. Police in Dallas police recently announced that Japanese-Americans are not welcome there. Utah State University has stated that it will reject Japanese-American students who wish to continue their education after being resettled in Utah.

A number of Japanese-Americans who have been living in the western states for years have also expressed opposition to welcoming evacuees. Japanese-American residents of Ogden, Utah have said that new arrivals might “endanger their good reputation.”

Until these disputes are addressed, the WRA has stopped all voluntary resettlement. However, forcible resettlement by the military continues to occur. Japanese-Americans are being moved to several camps: three located in inland California, one in Idaho and one in Arizona. Each camp will hold approximately 10,000 to 20,000 evacuees.

Earlier this week, the War Department tried to reassure the hesitant western state officials, stating that the relocation process is designed for minimal disruption to the areas taking in evacuees. During a session in Salt Lake City, spokesmen for the military and the federal government explained that the relocation program is meant to limit any postwar problems or economic difficulties.

Despite these explanations, the fact remains that all Japanese-Americans who planned to voluntarily evacuate without military escort will not be able to do so. All evacuees at Military Area No. 1 (which includes the western half of Washington and Oregon, and large parts of Arizona and California) will now have to remain there until they are escorted to the relocation centers under army supervision.

Japanese-Americans who chose to evacuate on their own have done so to avoid degrading evacuation orders under military conditions. Many have also preferred the comfort of their private cars as opposed to being crammed into buses and trains. Mary Vantura, a Japanese-American living in San Francisco, recently filed suit against humiliating military evacuation conditions. She claimed she was “unlawfully and arbitrarily restrained of her liberty” by evacuation commanders, who restricted her movements and issued curfews requiring her to remain indoors from 8 p.m. to 7 a.m. Her petition to evacuate independently was denied.

Members of the Mochida family awaiting their evacuation bus in Hayward, Calif. From Flickr.

However, many Japanese-Americans who have voluntarily evacuated to these unwelcoming towns are willingly returning to their homes on the West Coast to be later removed under Army supervision. Evacuees were shocked by the unwelcoming environment. Farmers were among those who received the most unfriendly reception. Japanese-Americans who grew vegetables on their previous farms were criticized for failing to have the same success with sugar beets in the inter-mountain areas upon relocation. The government is conducting survey to determine how many Japanese-Americans who voluntarily relocated now wish to come back to their homes and seek the Army’s protection in the resettlement process.

Many inland state officials however, still worry about what their cities will look like post-relocation and post-war. Milton Eisenhower, director of the War Relocation Authority, was asked during the session in Salt Lake City if Japanese will be moved back or remain after the war is over. Eisenhower replied that since this was a matter of executive action, the question would be decided by executive action alone—that is, by the president. “Long-range social programs by executive orders cannot be predetermined,” said Eisenhower. The future of the Japanese evacuees and their host cities evidently remains unclear.

Sources:

By R. T. (1942, May 04). Resettlement of japanese involves unusual problems. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/docview/151568508?accountid=13793

Special to THE NEW,YORK TIMES. “Effects of Moving Aliens Will be Guarded, Heads of Nine Western States are Assured.” New York Times. Apr 08 1942: 11.

LAWRENCE E DAVIES, “COAST ALIENS SEEK REMOVAL BY ARMY.” New York Times. Apr 09 1942: 7.

LAWRENCE E DAVIES, “EVACUATION STAY DENIED TO JAPANESE.” New York Times. Apr 23 1942: 15.

“COAST FILIPINOS AID JAPANESE WIVES.” New York Times. Apr 20 1942: 4.