Working in the Duke University archives in 2005, Assistant Professor James J. Kimble almost didn’t open the plain folder marked “scrap metal drives.” But the familiar front page of a newspaper from his home state of Nebraska caught his eye, and after a few minutes, the story of the 1942 Nebraska Scrap Drive pulled him in.

Working in the Duke University archives in 2005, Assistant Professor James J. Kimble almost didn’t open the plain folder marked “scrap metal drives.” But the familiar front page of a newspaper from his home state of Nebraska caught his eye, and after a few minutes, the story of the 1942 Nebraska Scrap Drive pulled him in.

That dusty folder led to “Scrappers: How the Heartland Won World War II,” a documentary about the World War II home-front campaign that fueled steel production for the war while galvanizing the nation behind the conflict.

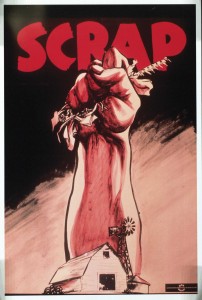

Conceived by Henry Doorly, publisher of the Omaha World-Herald, the Nebraska Scrap Drive collected more than 67,000 tons of scrap metal in a matter of weeks for the U.S. war effort. More successful than anyone predicted, the drive was later replicated nationally, jump-starting the nation’s scrap collection and keeping American soldiers properly armed.

In his research about the long-forgotten campaign, Kimble realized that as much as the scrap drive was about steel, tanks and airplanes, it was really a celebration of the power of community and creative competition. Pitting town against town, school against school, the Nebraska drive and the national effort that followed inspired Americans to get behind the war.

“This story has drama, a sense of conflict. What a lot of people think about the home front is that people did everything they were asked. But often they had to be coaxed,” said Kimble, whose scholarly research focuses on propaganda. He wrote a journal article on the drives, but believed they deserved more. “There were lots of possibilities for visuals.

I began to think it could be a documentary.”

So the first-year professor at Seton Hall gave his article to movie producer and Associate Professor Thomas R. Rondinella ’81, a full-time member of the Department of Communication and the Arts since 1996 and now its chairman. Kimble sheepishly admits he believed he was handing off the project — “I thought my part was done,” he said, grinning at the memory — but Rondinella would have none of that.

“I told him, ‘You are the propaganda historian, I don’t know anything about Nebraska.

I can’t do it without you,’ ” Rondinella said.

The pair devoted five years to the project — the first film for Kimble and the first documentary for veteran filmmaker Rondinella. They drove to Nebraska five times to interview residents who participated in the drives and to visit the World-Herald archives and those of local historical societies. Kimble conducted the interviews and wrote the script. Rondinella handled the sound, lighting and video and did much of the editing.

“Scrappers” links the World War II campaign to contemporary America by drawing parallels between the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the 9/11 attacks. The professors use the drive as a lens to examine today’s home-front efforts. The idea wasn’t to point fingers, Rondinella said, so much as to spark discussion about the participation and awareness of today’s citizens in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

“Our government is afraid to challenge us, (afraid) of not getting re-elected, of getting people angry,” said Rondinella, adding that he hopes the movie pushes more Americans to become engaged in civic life.

Americans needed to be coaxed into action in 1942, he notes. As the nation’s factories went into overdrive to support the war effort, federal officials in Washington pleaded with citizens to collect and donate their metal junk. Few paid attention until the editor of the Omaha newspaper came up with the idea of a contest. Omaha’s railroads quickly got behind the effort, and the World-Herald published daily stories encouraging participation.

The newspaper’s front page featured a daily tally, not unlike baseball box scores, of each county’s collection and per capita total. For three weeks, every Nebraska business, parent and child was swept up in the scrap metal craze.

“It was insane. It was inspiring,” said Rondinella, noting that Nebraska farmers would work a full day in their fields and then scavenge the ditches at night. After the 9/11 attacks, “Our government told us to go out shopping. We don’t do anything today.

I think politicians are afraid to ask.”

Everyone was involved. Omaha movie theaters offered children free admission for five pounds of scrap, attracting 12,000 kids and tons of salvage in one day. Baseball teams played games for scrap, couples held parties for scrap-bearing guests. A 6-year-old boy gave his tricycle to the campaign, while enthusiastic teenagers began dismantling a farmer’s working windmill before he drove them off.

Melba Glock was a little girl when she and her cousin used a giant magnet they had found to search the alleys around their homes.

“We were a bunch of kids and you know how kids are. Someone says, ‘Let’s do this’ and we do it. We don’t know why,” she said.

Although the scrap drives were crucial to the war effort, over time they have been forgotten. Kimble suggests the effort of finding and collecting junk lacks the glamour of Rosie the Riveter and other marquee symbols of WWII, and thus the scrap drives may have lost their place in the historical record. But the drives merit celebrating for both their practical result (the production of guns and planes) and the patriotic spirit they helped to spark.

In search of historians to provide expert commentary for the film, the pair quickly learned they were the experts. “I was not familiar with the scrapper effort, and I don’t think many Nebraskans were,” Nebraska Humanities Council Associate Director Mary Yager said. “It was important to share that.” The council provided crucial funding to complete the film, which has been broadcast on Nebraska public television and is now in the collections of hundreds of libraries around the country.

Many who knew of the campaign didn’t have a sense of the whole story, said Research Specialist Gary Rosenberg of the Douglas County Historical Society in Omaha, an important resource for the filmmakers.

“I didn’t realize Nebraska played such a pivotal role,” Rosenberg said.

Even those who participated in the drives didn’t grasp its significance. Glock, who now lives in Rising City, attended one of the premiere screenings the professors hosted in seven Nebraska locations last year.

“I was enlightened a great deal,” Glock said. “It laid the foundation for what brought about the drives.”

Christopher Amundson, editor and publisher of Nebraska Life magazine, believes the documentary’s message goes beyond the scrap drives to focus on human nature. “It appeals to the better nature that we have in our hearts,” Amundson said. “We as humans want to belong to something bigger than ourselves and we want to help.

“I look back, and I’m a little envious of what they had,” he continued. “To be able to pull together that way, there was so much loyalty, so much service.”

Kimble said the premiere screenings revealed the sense of accomplishment the citizens felt about the drive and their leadership role in the national effort. Many scrappers contrasted the community spirit of their time with the more partisan sensibility of today. “The challenge is to inspire today’s generation. To ask questions that we hope are provocative,” he said. “‘How are you involved? What are your contributions? Are there ways to build connections?’ ”

That’s the film’s lasting power, says Glock. “They had a vision of something from our past that made a tremendous contribution to what we call the war effort,” the child scrapper said. “There was patriotism, enthusiasm, loyalty. They brought that out.

“Makes one wonder,” she added. “Will we see that again?”

– Peggy McGlone ’87 is an arts reporter for the Star Ledger.