The Munsee-Speaking Lenape Indians

The Watering Place at the northeast corner of Staten Island was first seen by Europeans when the explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano and his crew on the Dauphine sailed into the upper bay of New York Harbor in April 1524. Explorers after Verrazzano, including Henry Hudson in 1609, and merchant mariners in the early colonization period stopped at the Watering Place to replenish their ships with water from a spring emptying into the bay. Verrazzano described the Indians that he and others encountered in the hills of New York Bay in his letter to the King of France,

“Sono di colore bruno, non molto diversi dagli Etiopi. Hanno capelli neri e folti, non molto lunghi […] Sono ben proporzionati, di statura media, qualche volta superiore alla nostra, con il torace ampio, le braccia robuste, le gambe e le altri parti del corpo ben strutturate. Hanno gli occhi neri e grandi, lo sguardo attento e vivace. Non sono dotati di una grande forza fisica ma sono di intelligenza acuta e sono corridori agili e molto resistenti […] Sono molto generosi. Tutto quello che hanno sono disposti a darlo. Stringemmo con loro una forte amicizia.” (G. da Verrazzano, lettera a Francesco I re di Francia, Luglio 1524) [from https://www.verrazzano.com/la-scoperta-di-new-york/, 9/25/18 ].

Google’s AI translator translates this text as:

“They are brown, not very different from the Ethiopians. They have black hair and thick, not very long […] They are well proportioned, of average stature, sometimes higher than ours, with the ample thorax, the sturdy arms, the legs and the other parts of the body well structured. They have black and big eyes, attentive and lively gaze. They are not equipped with a great physical strength but are of acute intelligence and are agile runners and very resistant […] They are very generous. All they have are willing to give it. We tightened a strong friendship with them. (G. da Verrazzano, letter to Francis I Kings of France, July 1524). ” [Google Translate, 9/25/18].

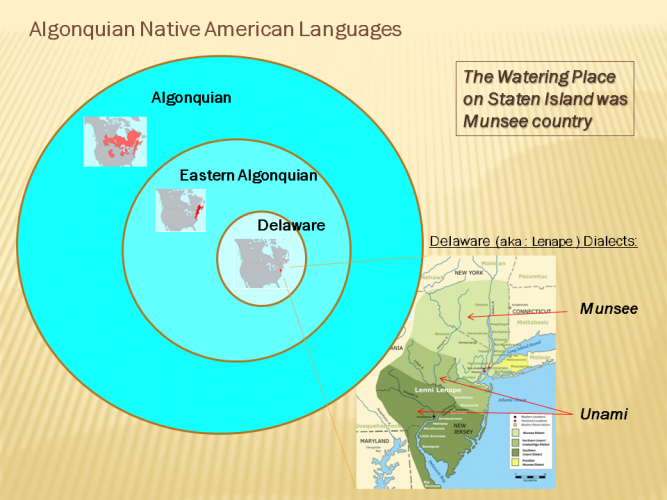

The Indians described in Verrazzano’s letter were the Lenape. The late Herbert C. Kraft of Seton Hall University, anthropologist and archaeologist, identified the Lenape Indians living north of the Raritan river as Munsee-speaking bands (Kraft, 2001). Today scholars appear to have adopted the name Munsee Indians to describe the Lenape from the lower Hudson and upper Delaware River valleys (Goddard, 2010; Grumet, 2009). The Watering Place was Munsee Indian country.

The Venn diagram shows how the Munsee dialect fits within the greater category of Algonquian Native American languages. The Lenape are described in the scholarly, trade, and popular literature by several different names. Modern scholars appear to have adopted Munsee Indians for the name of the Lenape north of the Raritan river which includes the Watering Place. (This image was created with edited maps from the Wikipedia Lenape and related pages).

The first estimate of the number of Munsee Indians living on Staten Island can be found in the the writings of Isaack de Rasieres who sailed to the New York Bay (at the time, New Netherland ) following his 1626 appointment by the Dutch West India Company as Secretary of New Netherland. In a letter to Samuel Blommaert, the director of the Dutch West India Company, Rasieres described in the parlance of his day what he saw when he sailed into the narrows of New York Bay on July 27th 1626 from his ship Het Wapen van Amsterdam (The Arms of Amsterdam).

Between the Hamels-Hoofden [the narrows] the width is about a cannon’s shot of 2,000; the depth 10, 11, 12 fathoms. They are tolerably high points, and well wooded. The west point is an island [Staten Island], inhabited by from eighty to ninety savages, who support themselves by planting maize. The east point is a very large island [Brooklyn/Long Island], full 24 leagues long stretching east by south and east-southeast along the sea-coast, from the river to the east end of the Fisher’s Hook [Montauk].

Also documenting his journey through the New Netherland territory in 1679 was Jasper Danckaerts, founder of a colony in what is now the State of Maryland. On October 11th, 1679, a Wednesday, he visited Staten Island and wrote about the Watering Place in his journal (p. 69).

We embarked early this morning in his boat and rowed over to Staten Island, where we arrived about eight o’clock. He left us there, and we went on our way ….. On the north or northwest is New Garnisee [Jersey], from which it is separated by a large creek or arm of the river, called Kil van Kol. The eastern part is high and steep, and has few inhabitants. It is the usual place where ships, ready for sea, stop to take in water, while the captain and passengers are engaged in making their own arrangements and writing letters previous to their departure. The whole south side is a large plain, with much salt meadow or marsh, and several creeks.

On a Saturday earlier in his voyage, September 23, he describes his encounter with the Munsee Indians. He also describes a settlement along the South Beach area of Staten Island (p. 35)

As soon as you begin to approach the land, you see not only woods, hills, dales, green fields and plantations, but also the houses and dwellings of the inhabitants, which afford a cheerful and sweet prospect after having been so long upon the sea. When we came between the Hoofden, we saw some Indians on the beach with a canoe, and others coming down the hill. As we tacked about we came close to this shore, and called out to them to come on board the ship, for some of the passengers intended to go ashore with them ; but the captain would not permit it, as he wished, he said, to carry them, according to his contract, to the Manathans, though we understood well why it was. The Indians came on board, and we looked upon them with wonder. They are dull of comprehension, slow of speech, bashful but otherwise bold of person, and red of skin. They wear something in front, over the thighs, and a piece of duffels, like a blanket, around the body, and this is all the clothing they have. Their hair hangs down from their heads in strings, well smeared with fat, and sometimes with quantities of little beads twisted in it out of pride. They have thick lips and thick noses, but not fallen in like the negroes, heavy eyebrows or eyelids, brown or black eyes, thick tongues, and all of them black hair. But we will speak of these things more particularly hereafter. After they had obtained some biscuit and had amused themselves a little, climbing and looking here and there, they also received some brandy to taste, of which they drank excessively, and threw it up again. They then went ashore in their canoe, and we having a better breeze, sailed ahead handsomely.

There were earlier attempts by the Europeans to establish a settlement on Staten Island. The first settlement was established at the Watering Place by David Pietersen De Vries, and another attempt was made by Cornelius Melyn but conflicts with the Munsee Indians ended these first settlements as witnessed in the following excerpt of a letter from Johannes Bogaert, Dutch clerk of New Amsterdam, to Hans Bontemantel in Amsterdam (p. 386).

On the 21st [Oct, 1655] we sailed for the North river, from Staten Island, by the watering-place, and saw that all of the houses there, and about Molyn’s [Melyn] house, were burned up by the Indians.

So the first attempted European settlement on Staten Island was at the Watering Place. What is the evidence for this claim?

Another curious thing is that there is no indication of American Indian longhouses on Staten Island. Does this mean that there were no Munsee Indians on Staten Island in 1639? Not necessarily. There is plenty of evidence of American Indian presence on Staten Island for thousands of years, but that is a story for another time.

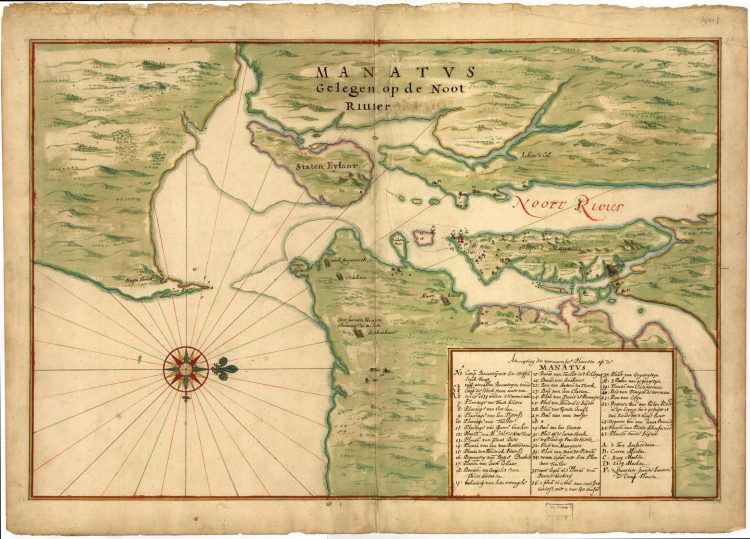

The Harrisse copy of the Manatus map from the archives of the Library of Congress. The small symbol indicating the presence of a farm near the hills on the north end of Staten Island is the Watering Place, but the symbol is missing the map key number. A scrollable, high definition version of the map is available from the Library of Congress.

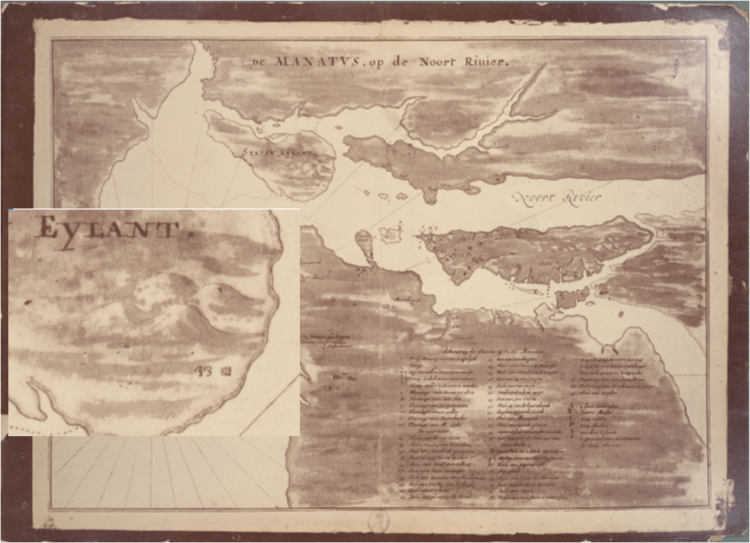

The Castello copy of the Manatus map. The symbol for the farm at the Watering Place is indicated as #33 (see enlarged area). On the map key for the Castello and the Harrisse copies #33 reads “Plan van Davidt Pietter.” From NY Public Library Digital Collection.

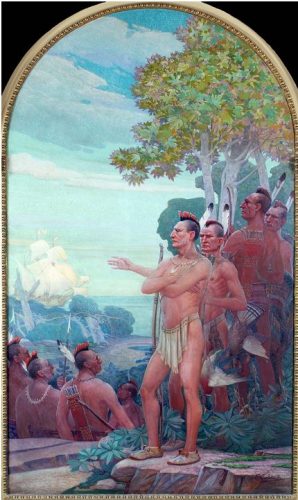

In the lobby of the Staten Island Borough Hall in St. George there are several 6 ½ by 13-foot oil-on-canvas murals painted by Frederick Charles Stahr through the Federal Works Project Administration (WPA) and installed by 1940. The mural shown here represents the Munsee Indians at the Watering Place and is titled “Henry Hudson Anchors off ‘Staaten Eeylandt’, 1609”.

The Munsee Name

According to Ives Goddard (2010, p. 278), curator and senior linguist in the Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution, the Munsee name most likely derives from the northern Lenape Indian word for ‘island’ and can be translated as ‘person of the island’. The Munsee word for ‘person at or on the island’ is Minisink (also see Kraft, 2001, p. 7; Grumet, 2009, p. 6). The island that is being referred to here is located in the Delaware River, north of the Delaware Water Gap and is still known today as Minisink Island. Numerous artifacts have been found in the area as well as burial remains. In 1914 the Museum of the American Indian in New York undertook a study of Munsee Indian skeletons discovered in a cemetery directly opposite of Minisink Island on the New Jersey side (Hrdlicka, 1916 ). It is believed that the Munsee name originally referred to the band of Lenape Indians living on Minisink Island and the surrounding region. However, all Munsee-speaking Lenape bands were identified by the Munsee name when they formed a coalition or nation as they were forced into exile before the start of the Revolutionary war. The Munsee Indians were forced out of the Delaware and Hudson River Valley into areas surrounding the Susquehanna and Allegany rivers (Pennsylvania) and Ohio river (Grumet, 2009). Descendents today are scattered in various places including Oklahoma and Ontario Canada. http://www.munsee.ca/history

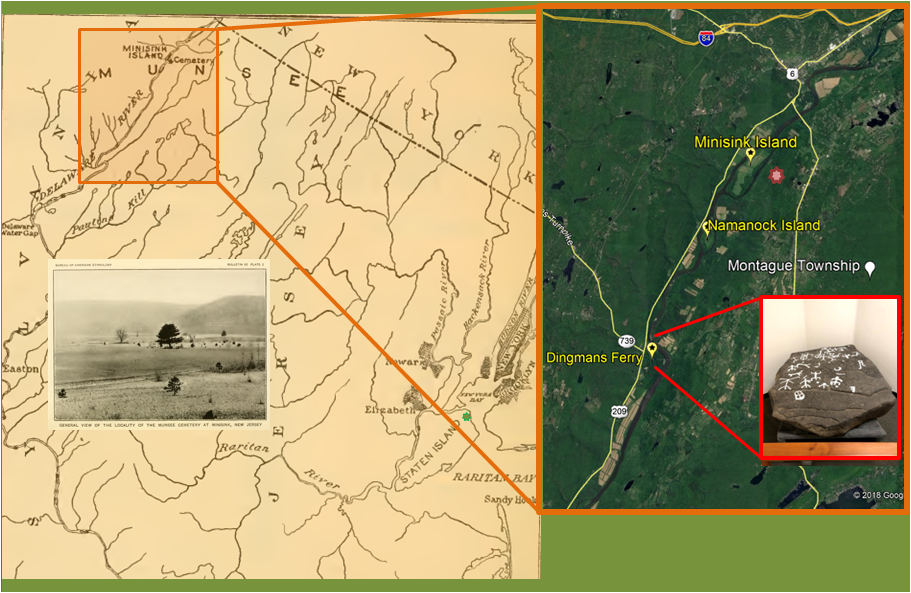

The map on the left side of this image showing the location of Minisink Island and the picture insert showing the grounds of the Munsee Indian cemetery at the time of its discovery is from Hrdlicka (1916). I added a green star on Staten Island to mark the location of the Watering Place. The Minisink Island area on the map is expanded on the right side with help from Google Maps; the cemetery area is marked with a red star. In 1965, while visiting his family’s cabin on the New Jersey side of the Delaware river near Dingman’s Ferry, Rudyard Clune Jennings discovered a petroglyph with what appeared to be prehistoric American Indian carvings. Dr. Herbert Kraft studied the artifact and confirmed its authenticity as a Munsee Indian artifact carved 500 to 5000 years ago. This large artifact ( 5 feet x 4 feet x 9 ½ inches thick) was donated to Seton Hall University and is on display on the second floor of the Seton Hall University library in South Orange, New Jersey.

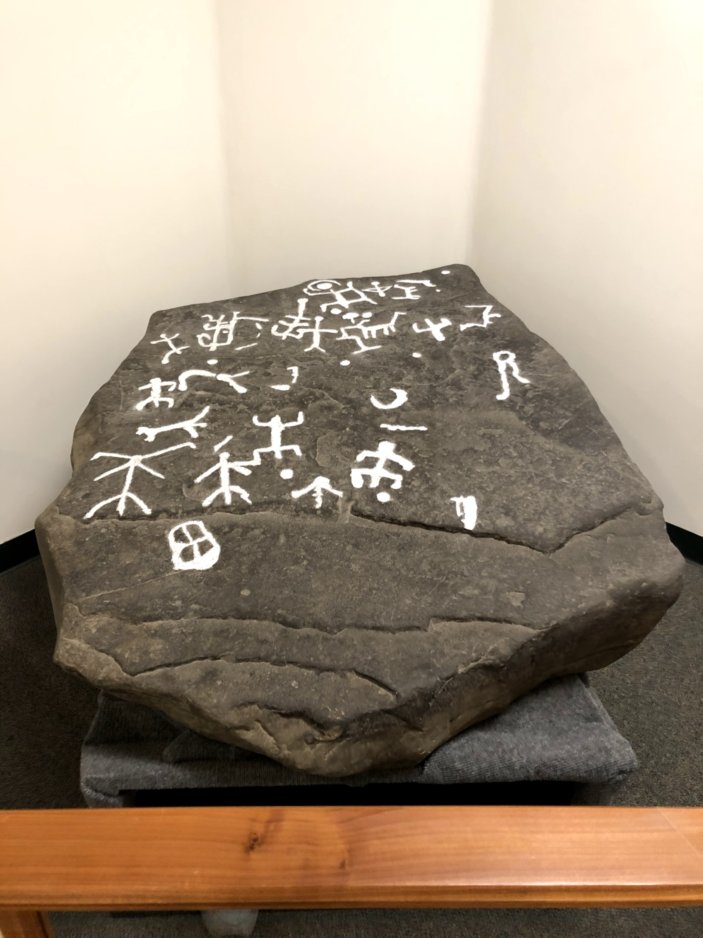

The Jennings Petroglyph Up Close

The engravings on this massive American Indian artifact have been outlined in white for easier study. Herbert Kraft did not attempt to interpret the meaning of the petroglyph figures. Nevertheless, several human and animal stick figures are easily identifiable. More recently it was suggested that some of the carvings may represent the stars. Do you see a representation of the Orion constellation and Orion’s Belt? The Jennings Petroglyph is on display at the Seton Hall University Library in South Orange New Jersey.

The engravings on this massive American Indian artifact have been outlined in white for easier study. Herbert Kraft did not attempt to interpret the meaning of the petroglyph figures. Nevertheless, several human and animal stick figures are easily identifiable. More recently it was suggested that some of the carvings may represent the stars. Do you see a representation of the Orion constellation and Orion’s Belt? The Jennings Petroglyph is on display at the Seton Hall University Library in South Orange New Jersey.———————————

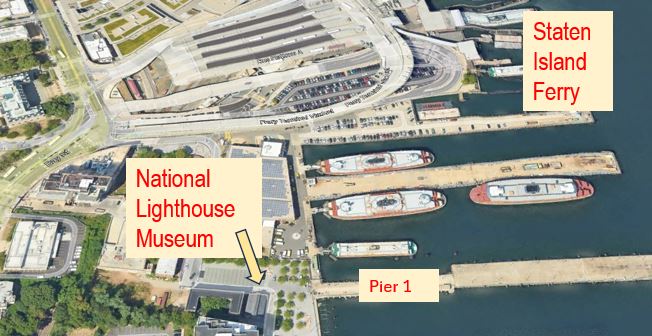

The National Lighthouse Museum located on the federal government section of the former quarantine grounds sponsors an annual Lighthouse Point festival. In 2018 the Red Storm Drum and Dance Troupe, a Native American educational and performance group from Staten Island, participated in the festival. The performance seen in the video below took place near Pier 1. Although rebuilt several times depending on the needs of the institution, the pier served the original US Revenue Cutter Service, the US Lighthouse Service, the U.S. Coastguard, and the NYC Department of Transportation. Now in the hands of the City Economic Development Corporation the pier provides public access to majestic views of New York harbor. But of course, this location first served the original inhabitants of Staten Island. Although there is no evidence of a permanent Lenape encampment in this area, there is evidence that the Native Americans also made use of this place.

References

Danckaerts, J. & Sluyter, P. Journal of Jasper Danckaerts, 1679-1680. 1911 translation by James, Bartlett Burleigh & Jameson, J. Franklin

de Rasiere, Isaac (1628). New Netherland in 1627. Letter from Isaack de Rasieres to Samuel Blommaert, found in the Royal library at the Hague, and transmitted by Dr. M. F. A. to the N. Y. Historical Society. Translated from the original Dutch by J. Romeyn Brodhead

Goddard, I. (2010). The origin and meaning of the name “Manhattan”. New York History, 4, 277-293.

Grumet, R. S. (2009). The Munsee Indians: A History. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Hrdlička, A. (1916). Physical anthropology of the Lenape or Delawares, and of the Eastern Indians in general. Washington: Government Printing Press.

Kraft, H. C. (1965) The first Petroglyph Found in New Jersey, Pennsylvania Archaeologists, 35(2) 93-100.

Kraft, H. C. (2001). The Lenape-Delaware Indian Heritage 10:000 BC to AD 2000. NJ: Lenape Books.

Letter of Johannes Bogaert, Dutch clerk of New Amsterdam, to Hans Bontemantel in Amsterdam, 1655. From Rutgers University Library Special Collection