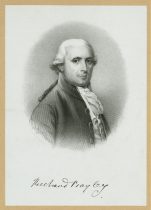

Dr. Richard Bayley – Physician, Educator, and Researcher

Richard Bayley was born in Fairfield Connecticut in 1745 to William Bayley and Susanne LeConte and was raised in New Rochelle, New York. Bayley first lived on Staten Island with his mother’s cousin, Pierre LeConte, while studying medicine with Dr. John Charlton, the son of Reverend Richard Charlton, rector of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church on Staten Island.[1] Medical schools were not yet prevalent in the colonial times and medical education involved an apprenticeship with a reputable physician. The best American physicians continued their medical studies by journeying to Europe to work with the leading medical men and researchers. In 1769, the same year he married his teacher’s sister, Catherine Charlton, Bayley left for England to study with the famous Scottish anatomist and surgeon, Dr. William Hunter.[2]

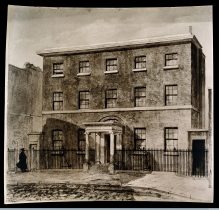

Bayley studied at Dr. William Hunter’s house and School of Anatomy on 16 Great Windmill Street, London

“Scarce any science or art requires the protection of a prince more than Anatomy, as well on account of its great use to mankind, as because it is perfected by the prejudices, both natural and religious, of the multitude in all nations … that few men, even of the profession, ever attempt the practical part: and, without practice, there can be no great share of real and useful knowledge.” Quote from McCormack, H. (2015) William Hunter’s Great Windmill Street Museum and Anatomy Theatre. In: Drawing A Pre-eminent Skill, 27 Mar 2015, Royal Academy of Arts, London. p 2.

Richard Bayley was among the earliest students of Hunter’s London School of Anatomy. The anatomy school at 16 Great Windmill Street would go on to gain great fame and influence in medicine.

William Hunter: his home and anatomy school, London. Source: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Only the façade of the Hunter house and Anatomy School remains on 16 Great Windmill Street, London. Google Earth Image 2/4/17

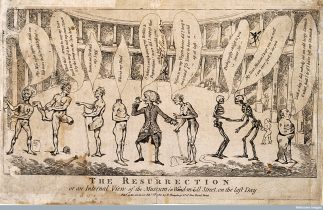

Science and medicine often advance faster than our ethical practices and codified laws. Ethical and moral concerns about the practice of dissection of human cadavers has a long history. In the poster below the Christian belief in resurrection and Hunter’s anatomical study of the human body suggests conflict. Richard Bayley would experience conflict first hand when a mob of angry New Yorkers, concerned about the rumored unethical practice of grave robbing by medical students, destroyed Bayley’s anatomical collection at the New York Hospital and then sought to capture and punish the doctors and medical students. The Doctor’s Mob riot took place in 1788 and was the first significant riot in the nascent United States that resulted in the death of rioters.

William Hunter in his museum in Windmill Street on the day of resurrection, surrounded by skeletons and bodies, some of whom are searching for their missing parts. Click on the image to read the dialogue. Engraving, 1782.Source: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Bayley sailed to London twice to study anatomy with William Hunter. During his first trip he wrote to his wife Catherine about his accomplishments:

“The Anatomist Dr Hunter gives me great encouragement and thinks that by applying myself closely to anatomy and the operative part of surgery this winter (1770) which I shall have entirely at my power in his dissecting rooms and after that to be punctual next summer in my attendance on the hospitals I may with ease qualify myself for a practitioner in surgery in any part of the world adding in the fullness of confidential intercourse I will mention to you that they tell me I have a very uncommon dexterity with the knife but this London is a sad place for flattery .”

Quote is from Thatcher, James (1828) American Medical Biography or Memoirs of Eminent Physicians who have Flourished in America, to which is Prefixed a Succinct History of Medical Science in the United States from the First Settlement of the Country. p 157.

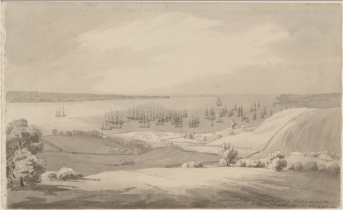

Upon his return to America in 1772 Bayley established a practice with his brother-in-law and former teacher only to voyage again to London in 1775 for another year of study at William Hunter’s anatomy school. Bayley returned to America on July 12, 1776 in Admiral Richard Lord Howe’s fleet as British surgeon, anchoring opposite the Watering Place in present day St. George/Tompkinsville and near the location where Bayley would help establish the Quarantine Grounds and Marine Hospital. He would serve as port officer of the Quarantine for several years until succumbing to an infectious disease in 1801. The lithograph below shows the arrival of the British fleet off of the Watering Place in July 1776. Perhaps Bayley remembered the number of ships that this area of the New York Harbor could accommodate when he recommended the Watering Place for the location of the Quarantine Grounds.

View of the Narrows between Long Island & Staaten Island with our fleet at anchor & Lord Howe coming in–taken from the height above the Waterg. Place Staaten Island. 12th July 1776. drawn by Archibald Robertson. From the New York Public Library Digital Collection.

Bayley established himself as a respected physician, educator, and researcher. Upon the death of his first wife Catherine in 1777, Bayley resigned his commission as British army surgeon and became active in medical education, giving private instruction in surgery as suggested by an advertisement he placed in the “Royal Gazzette” July 5th, 1780,

Mr. Bayley, presents his compliments to the gentlemen who did him the honor of attending the operation in surgery last Winter and will be happy to see them at his house on Friday the 7th at five o’clock p.m.

Bayley was an innovative surgeon, performing the first successful amputation at the shoulder joint, and possessed excellent observational skills that served him well as surgeon and researcher. His skillful pathological observations suggested to him that the croup (diphtheria) was different from angina trachealis (strep throat) and resulted in new modes of treatment that the medical community adopted. Bayley’s interest in research was well known. After the war, when Americans loyal to the crown of England were being chased out of the country, Bayley was accused of having experimented on American prisoners of war while he was stationed in Rhode Island as surgeon in the British army. William Smith, who was Chief Justice of the Province of New York as Guy Carleton oversaw the safe evacuation of loyalists from New York City, investigated the accusation and concluded that the charge was unfounded. A witness of Bayley’s conduct toward the prisoners of war was a patriot physician,

Thus, Sir, I have given the outlines of the Doctors conduct towards the wounded, but shall not do justice to him if I do not declare to you, that his conduct, was not only such as we had a right to expect from a generous enemy, but such as would meet with approbation, from a friend. – Doctor Silas Holmes [3]

Bayley therefore remained in America and continued his work as educator, physician and researcher. The era of the barber surgeons had ended by this time and medical students were seeking academic training. In 1785 Bayley began giving lectures on surgery and treated some of his patients in a building that would later become New York Hospital. His son-in-law Dr. Wright Post also taught anatomy in the building and made use of Bayley’s extensive anatomical collection. By 1788 the frequent and less than discreet dissections of human cadavers by students and their teachers triggered what became known as “The Doctor’s Mob” – the first significant riot of the new American nation.[4] A Virginia military officer writing to Virginia governor Edmund Randolph provided an account of the initial cause of the riot.

The Young students of Physic, have for sometime past, been loudly complained of, for their very frequent and wanton trespasses in the burial grounds of this city. . . . On Sunday last, as some people were strolling by the hospital, they discovered a something hanging up at one of the windows, which excited their curiosity, and making use of a stick to satisfy that curiosity, part of a mans arm or leg tumbled out upon them. The cry of barbarity was soon spread – the young sons of Galen fled in every direction – one took refuge up a chimney – the mob raised – and the hospital apartments were ransacked. [5] (p .1502)

Desiring to end the practice of dissection, and therefore the pressure to acquire bodies surreptitiously, the mob destroyed Bayley’s valuable anatomy collection. Bayley published a statement in the New York papers that he had never obtained any human bodies from graveyards for the purpose of dissection.[6] But the public was not convinced. The mob reformed the next day and threatened some of the doctors and medical students who authorities had locked in the city jail for their safety. When the mob approached the jail and failed to respond to Alexander Hamilton’s and John Jay’s pleas for calm, the mayor summoned the militia who proceeded to fire upon the crowd, killing four. The following year the New York State legislature passed an act making it illegal to remove dead bodies from cemeteries for the purpose of dissection and provided a source of cadavers for medical instruction and scientific advancement by authorizing justices to have the option to impose a penalty of death and dissection to criminals convicted of murder, arson or burglary.[8]

By 1792 the Trustees of Kings College (later Columbia College) appointed Dr. Richard Bayley as Professor of Surgery, but Bayley would become involved in the investigation of epidemics through his association with the Medical Society of the State of New York established in 1794 after the dissolution of the older medical society. It is to the Medical Society that the State of New York turned to for help when dealing with the epidemics that ravaged the city. In 1795 New York City experienced an epidemic of yellow fever that, although moderate compared to other epidemics in America, caused considerable concern.

“At a meeting of the Medical Society of the State of New York, held at the usual place, Sept. 4, 1795, The President read a letter from the Governor of the State to him, as President of this Society, on the subject of the present alarm in consequence of the disease in the upper part of the City for the Intercourse having been stopped between this City and Philadelphia by the Governor of Pennsylvania’s proclamation. After some conversation, Dr. Bayley, Dr. Tillary, Dr. Smith, Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Bard were appointed a Committee to answer it.”[9]

Bayley would later write to the governor urging state quarantine laws for ships arriving at the port of New York. He successfully persuaded Governor Jay to construct a state lazaretto on Bedloe’s Island (now Liberty Island) which the city of New York used for quarantine as early as 1738[10]. He also recommended reform for the treatment of the sick arriving on ships so that they would be removed to adequate quarters on land in a quarantine hospital. [11] By February 22 of the same year Governor John Jay appointed Bayley New York State Health Officer.[12]

Bayley published the results of h is investigations of the 1795 yellow fever epidemic the following year. [13] He approached the study of the epidemic by identifying the day and place in Manhattan where people fell ill and examined the relationship between peoples’ interaction with the sick and the man-made (e.g., refuse) and natural (e.g., weather) conditions of the local environment. In America the appearance of infectious disease was exotic as it was associated with the seasonal arrival of ships, thus anecdotal evidence suggested that the ships were bringing infectious diseases. But in Europe, disease appeared to materialize more randomly. This dissimilarity was most likely due to differences in population densities, with the larger overcrowded urban centers of Europe being able to better sustain endemic disease. The difficulty in perceiving a reliable association between disease and the arrival of ships in Europe may have contributed to the predominant belief that miasma – bad air arising from local unsanitary conditions- caused disease. The miasmatic theory would dominate scientific thinking about disease well into the 19th century. Although anecdotal evidence in America placed blame on foreign sources, Bayley’s systematic observations suggested that the origin of yellow fever was of local and not of foreign origin, arguing emphatically that epidemic diseases were “murderers of our own creating”.[14] Bayley noticed that the victims of yellow fever were mostly concentrated at the streets near the Manhattan docks. The city tolerated the expansion of the docks in lower Manhattan with all manners of landfill, including rotting refuse and animal carcasses. The drainage was also very poor in these areas resulting in stagnant pools of water and flooded basements after heavy rains.

is investigations of the 1795 yellow fever epidemic the following year. [13] He approached the study of the epidemic by identifying the day and place in Manhattan where people fell ill and examined the relationship between peoples’ interaction with the sick and the man-made (e.g., refuse) and natural (e.g., weather) conditions of the local environment. In America the appearance of infectious disease was exotic as it was associated with the seasonal arrival of ships, thus anecdotal evidence suggested that the ships were bringing infectious diseases. But in Europe, disease appeared to materialize more randomly. This dissimilarity was most likely due to differences in population densities, with the larger overcrowded urban centers of Europe being able to better sustain endemic disease. The difficulty in perceiving a reliable association between disease and the arrival of ships in Europe may have contributed to the predominant belief that miasma – bad air arising from local unsanitary conditions- caused disease. The miasmatic theory would dominate scientific thinking about disease well into the 19th century. Although anecdotal evidence in America placed blame on foreign sources, Bayley’s systematic observations suggested that the origin of yellow fever was of local and not of foreign origin, arguing emphatically that epidemic diseases were “murderers of our own creating”.[14] Bayley noticed that the victims of yellow fever were mostly concentrated at the streets near the Manhattan docks. The city tolerated the expansion of the docks in lower Manhattan with all manners of landfill, including rotting refuse and animal carcasses. The drainage was also very poor in these areas resulting in stagnant pools of water and flooded basements after heavy rains.

Intrigued with Bayley’s observations Dr. Valentine Seaman systematically mapped the location of yellow fever victims. [15] His map is one of the earliest cartographic maps of disease – earlier than John Snow’s 1854 Broad Street map of London’s cholera epidemic that is often credited as a breakthrough approach that helped identify contaminated water as the cause of London’s cholera epidemic.[16] But the power of an accurate and well-constructed cartographic map in revealing the cause of disease may be exaggerated.[17] Thus, the dominant explanatory construct at the time – the miasmatic theory – determined how Bayley and Seaman interpreted the empirical evidence that they collected. Relying on the prevailing theory’s explanatory power, Bayley also reasoned that disease was prevalent aboard ships arriving at the New York ports because the small, cramped filthy spaces on board the ships replicated the miasmatic conditions of the crowded dock areas of Manhattan. Of course today we know that the cause of yellow fever was more complex having both foreign and domestic contributions. The foreign source was the Flavivirus carried by the Aedes aegypti mosquito that fed on the blood of infected travelers and the local cause was the stagnant pools of water by the docks and in the basements of nearby buildings that allowed infected mosquitoes to flourish and claim new human victims. Nevertheless, Bayley‘s views had a significant impact on improving sanitary conditions in New York City (such as the introduction of buried sewers) and in establishing an approach to quarantine that persisted for about a century with some degree of efficiency.

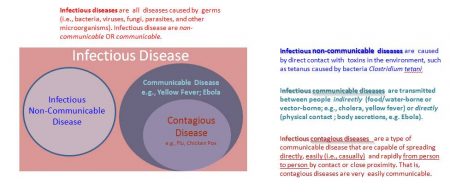

Bayley was also among the first physician researchers to recognize that not all infectious diseases are contagious. “Contagious diseases do not require the concurrence of certain causes to render them contagious; they are so under all circumstances”. His review of the evidence suggested that Yellow Fever did not always demonstrate the consistency of a contagious disease because contracting Yellow Fever seemed to require the presence of one or more unknown factors. He concluded that “ other diseases may, or may not be infectious, according to the conditional state in which they are placed.” Contrary to the opinions of most of his contemporary colleagues, including the famous Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia, Richard Bayley correctly concluded that Yellow fever was an infectious, but not a contagious disease.

Infectious, Communicable and Contagious Diseases: What’s the difference?

Using the terminology outlined here it is clear that Richard Bayley recognized Yellow Fever to be an infectious communicable disease, but not a contagious disease. He was not able to accurately explain why this was so, however, because the medical profession’s mistaken consensus in his time was that disease was caused by miasma (noxious “bad air”). The scientific discovery of germs and the confirmation of germ theory would come a century later. We now know that the Yellow Fever virus does not spread directly from person to person but requires an intermediary (a vector) in the form of a mosquito.

Using the terminology outlined here it is clear that Richard Bayley recognized Yellow Fever to be an infectious communicable disease, but not a contagious disease. He was not able to accurately explain why this was so, however, because the medical profession’s mistaken consensus in his time was that disease was caused by miasma (noxious “bad air”). The scientific discovery of germs and the confirmation of germ theory would come a century later. We now know that the Yellow Fever virus does not spread directly from person to person but requires an intermediary (a vector) in the form of a mosquito.

Bayley traveled frequently to Albany (the seat of New York Government) to argue to the legislature for permission to build a quarantine station on Staten Island.[18] On February 25, 1799 New York State used its power of eminent domain to obtain from St. Andrews Church thirty acres of property at the Watering Place. Upon another request for advice from the governor of New York, a subcommittee of the Medical Society headed by John Charlton identified the Staten Island property as the best location for the new quarantine facilities [19]

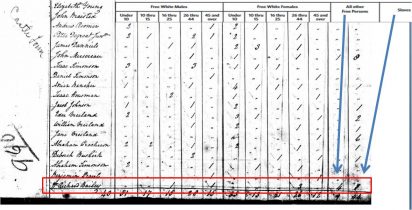

1800 Census record of Dr. Richard Bayley at the Quarantine Grounds

1800 Census listing the number of people living at Bayley’s residence at the Quarantine Grounds. Ancestry.com. 1800 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

If you would like to see all of the names and data from the 1800 Castle Town census click here to open in a new browser tab the complete list from a genealogy web site. See if you can find the name of a famous American historical figure. Curious, but in a hurry? Look at the section with the entries between 304 and 341. By the way, Dr. Richard Bayley (Bailey) is entry # 282.

Bayley would serve dutifully as Health Officer administering to the immigrants and seaman arriving at the Staten Island Quarantine Grounds. His daughter Elizabeth Ann Seton, who would later convert to Catholicism and become the first American born saint, was heartened by the poor Irish immigrants that she observed at the Quarantine Grounds while staying at her father’s residence during the summer months. [20] In 1801 while performing his duty as State port officer Bayley contracted an infectious disease and died on Monday, August 17. He is buried on Staten Island in St. Andrew’s cemetery immediately next to the east wall of the church.

Michael Vigorito

[This text is a part of a presentation that I gave at the “Staten Island in American History and 21st-Century Education” Education Symposium/Academic Conference, College of Staten Island-CUNY, Staten Island, New York, March 19-20, 2011].

References

[1] Joseph I. Dirvin, Mrs. Seton. (New York: Farrar, Straus & Sudahy, 1962).

[2] James Thacher, American Medical Biography. (Boston: Richardson & Lord and Cottons & Barnard, 1828), 1: 157.

[3] William S. Smith to George Clinton, 20 October, 1783. Public papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, 1777-1795 (Albany: The State of New York, 1904), 8: 266-267.

[4]Jules C. Landenhein (1950). “The Doctor’s Mob of 1788,” The Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 5 (1950): 23.

[5] Whitfield J. Bell, “Doctors Riot, New York, 1788,” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 47 no. 12. (1971) : 1501-1502.

[7] Landenheim, 37.

[8] Laws of the State of New York Passed at the Sessions of the Legislature. (Albany: Weed. Parsons & Company, 1887), 3: 5.

[9] James J. Walsh, History of Medicine in New York (New York: J. J. Little and Ives Co, 1919), 1 : 60.

[10] Walter A. Klein and George G. Reader, “Epidemic Diseases at the New York Hospital,” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 67, no. 5 (1991) : 439.

[11] John Jay to Richard Bayley, 22 February, 1796. The Papers of John Jay , New York State Library, Manuscripts & Special Collections, available from http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/jay/

[12] Richard Bayley to John Jay, n.d. December, 1796. The Papers of John Jay , New York State Library, Manuscripts & Special Collections, available from http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/jay/

[13] Richard Bayley, An Account of the Epidemic Fever Which Prevailed in the City of New York During the Part of the Summer and Fall of 1795. (New York: T. and J. Swords, 1796).

[14] Richard Bayley to John Jay, n.d. December, 1796.

[15] Seaman, Valentine, “An Inquiry into the Cause of the Prevalence of the Yellow Fever in New York,” in The Medical Repository, third Edition 1804, eds. Mitchell S.L. , Miller, E and Smith,E.H. ( New York: T & J Swords, 1804), 303-323.

[16] Edward R. Tufte. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, 2nd Edition. (Cheshire, Connecticutt: Graphics Press, 1992), 24.

[17] Howard Brody, Michael R. Rip, Peter Vinten-Johansen, Nigel Paneth, and Stephen Rachman, (2000). ”Map-making and Myth Making in Broad Street: the London Cholera Epidemic, 1854”. The Lancet, 356 (2000) : 64-68.

[18] Richard Bayley, Letters from the health-office, submitted to the Common Council, of the City of New-York (New York: John Furman, 1799)

[19] John Charlton to John Jay, 19 December, 1799. The Papers of John Jay , New York State Library, Manuscripts & Special Collections, available from http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/jay/

[20] Dirven, 1961, 56.