Lord Jeffery Amherst

When I first learned of a connection between Lord Jeffery Amherst and the Watering Place I thought – “Huh – how interesting is that! “ Knowledge of historical events enhance a sense of place by helping to construct a defined narrative of the place. The sense of place may be heightened further for a person when new knowledge about a place reveals a connection to one’s personal life, even if the association is just a subtle one. I have a connection with the Amherst name.

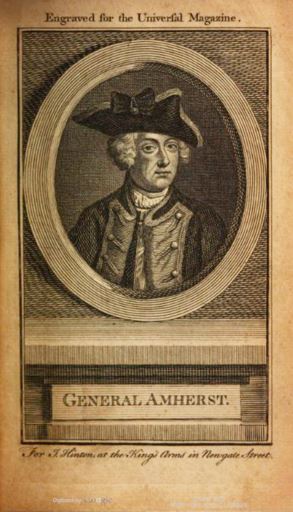

An article honoring Jeffery Amherst – “A short ELOGIUM of General AMHERST” – was published in The Universal Magazine of Knowledge & Pleasure February, 1761. This engraving of the general was between pages 100 and 101. He was knighted later that same year. HathiTrust Public domain, Google-scanned

Jeffery Amherst was an 18th century British military officer who was a master at logistics. That is, he was really good at the big picture of war – managing the procurement, maintenance, and transportation of military personnel and their supporting material (Sweeney, 2008). Amherst’s mastery of logistical arrangements early in the world war known as the Seven Years War (1756 – 1763) (what we refer to as the French and Indian War in America) earned him a promotion to commander of all British and colonial forces in North America. In 1761 under his supreme command the British defeated the French Canadians and their Native American allies. The French left North America but the Indians remained of course, occupying land west of the Alleghany mountains. The response of the Native American Indians to western expansion by the colonial invaders would later become a major issue for Amherst.

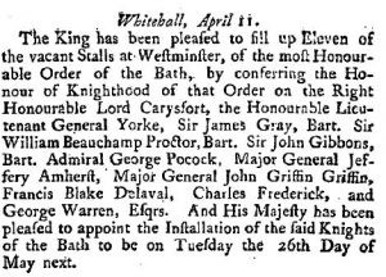

The Commander-in-Chief of the British and colonial Army – the hero of the North American campaign – was camped at the Watering Place (Bayles, 1887) when on October 25, 1761 in a modest ceremony he was made a knight of the Most Honorable Order of the Bath. This was the first time that a knighting ceremony took place in America. Because General Amherst was busy managing a war he could not attend the elaborate ceremony at Westminster Abbey in England where 10 other men received the same honor. Instead, the recently-appointed colonial governor of New York and military commander Major General Robert Monckton was asked to invest Amherst with the gold emblem and red sash of the Order of the Bath “in the most honourable and distinguished manner the circumstances will allow of.” (William Pitt to Robert Monckton, July 17, 1761).

Excerpt from The London Gazette numb. 10094 (April 7 to April 11, 1761). The King was George III who had just gained the throne upon the death of his grandfather George II.

A brief description of the ceremony at the Watering Place was reported in a British magazine

Major general Monckton then proceeded to put the ribbon over Sir Jeffery Amherst’s shoulder making an apology that circumstances would not admit of a more formal investiture. Jeffery Amherst upon receiving this order addressed himself to Major General Monckton in the following terms “Sir I am truly sensible of this distinguished mark of his majesty’s royal approbation of my conduct, and shall ever esteem it as such; and I must beg leave to express to you the peculiar satisfaction I have, and the pleasure it gives me, to receive this mark of favour from your hands.“ The British Magazine, Or, Monthly Repository for Gentlemen & Ladies, edited by Tobias George Smollett. London, 1761, p. 671

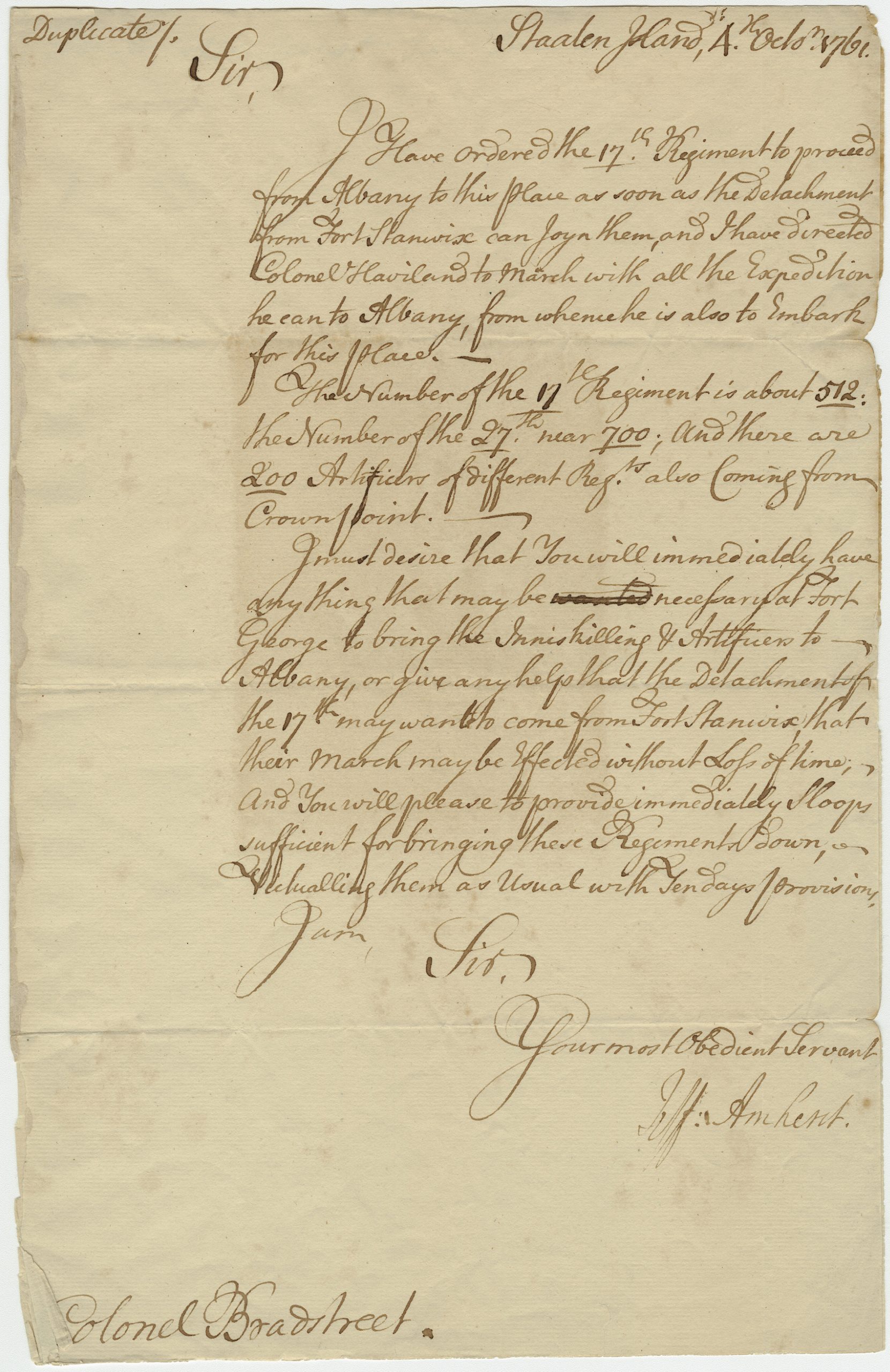

An example of Amherst’s logistical work can be seen in his letter to Colonel Bradstreet (October 4, 1761) who was encamped at Albany while Amherst was at the Watering Place. In this letter he directed regiments from several forts upstate New York to march down to the Watering Place on Staten Island. The map shows the location of the forts and the Watering Place.

Fort Stanwix National Monument is a United States National Historic Site in Rome, New York, managed by the National Park Service. The current fort is a reconstruction of the historic Fort Stanwix occupying approximately 16 acres of downtown Rome.

https://www.nps.gov/fost/index.htm

For historical markers throughout this location see:

http://revolutionaryday.com/usroute4/ftedward/default.htm

The Anvil Inn Restaurant (a blacksmith's shop in the 1840s) is located on the place that was once the outer wall of Fort Edward.

http://www.historiclakes.org/wm_henry/wm_henry_battle.html

“1755, Warren County, Village of Lake George. Located just South East of Fort William Henry on higher ground. Established after the Battle of Lake George in 1755. Improvements started in 1759 as base of General Amherst for his advance against French at Ft Ticonderoga, but only one bastion completed. (also buried remains of Ft Wm Henry destroyed 1757).” http://dmna.ny.gov/forts/fortsE_L/georgeFort.htm

27 Eagle Street, Albany, New York

"A British fort that stood from 1676–1789. Used by the British to defend the colonial frontier as it stood at Albany, then to garrison troops and store supplies in the effort against the French (French and Indian War). Eventually used by the American colonies during the American Revolution to jail British loyalists." http://nyhistoric.com/2012/04/fort-frederick/

In 1761 the British camp was at the Watering Place. Lord Jeffery Amherst was probably in one of the Forts on the hills at the Watering Place.

READ Amherst's Marching orders to the Watering Place.

While encamped at the Watering Place on Staten Island Lord Jeffery Amherst wrote to Colonel Bradstreet in Albany. In this letter he directed multiple regiments camped at several forts upstate New York to march down to the Watering Place on Staten Island.

From Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

From Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

My comments in brackets [ ] below.

Sir,

I have ordered the 17th Regiment [commanded by Monckton] to proceed from Albany [aka Fort Frederick] to this place [the Watering Place, Staten island] as soon as the Detachment from Fort Stanwix can joyn them and I have directed Colonel Haviland [probably at Fort Edward] to march with all the Expedition he can to Albany, from whence he is also to embark for this place.

The number of the 17th regiment is about 512. The number of the 27th near 700; and there are 200 Artificers [an artificer is skilled mechanic in the British armed forces] of different Reg. ts also coming from Crown Point.

I much desire that you will immediately have anything that may be necessary at Fort George to bring the Inniskilling [ this is the original name for the 27th regiment, raised in 1689 to protect the Irish town of Enniskillen] & Artificers to Albany or give any help that the detachment of the 17th may want to come from Fort Stanwix that their march may be effected without loss of time ; And you will please to provide immediately Sloops sufficient for bringing there a regiment down on [?????] them as usual with ten days provisions.

I am Sir, Your most obedient Servant, Jeff Amherst

Colonel Bradstreet

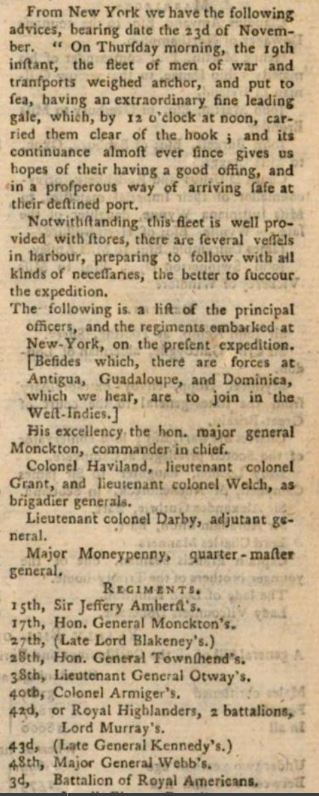

After the regiments had all arrived at Staten Island they set sail under the command of Major General Monckton toward the West Indies in the next phase of the Seven Years War. The expeditionary force would capture for the crown of England the island of Martinique from the French and Havana Cuba from the Spanish.

News report of Amherst's fleet setting sail from the harbor in New York Bay

The British Magazine, Or, Monthly Repository for Gentlemen & Ladies, November 1761, page 671

In honor of Jeffery Amherst’s earliest successes in America and his promotion to major general a district of the town of Hadley in Massachusetts was renamed Amherst in 1759 . And there is my connection with Amherst. My wife and I began our family in Amherst while earning our doctorates at the University of Massachusetts; we lived in family student housing for 5 years. My son later returned to Amherst to earn his Bachelor’s degree at Amherst College and his doctorate at UMass. So Amherst – the place, not the man – is very much a part of my family’s narrative. Learning about the man behind the town name is intellectually enriching and, as it turns out, makes for an interesting reflection on how people understand historical figures in the present.

In honor of Jeffery Amherst’s earliest successes in America and his promotion to major general a district of the town of Hadley in Massachusetts was renamed Amherst in 1759 . And there is my connection with Amherst. My wife and I began our family in Amherst while earning our doctorates at the University of Massachusetts; we lived in family student housing for 5 years. My son later returned to Amherst to earn his Bachelor’s degree at Amherst College and his doctorate at UMass. So Amherst – the place, not the man – is very much a part of my family’s narrative. Learning about the man behind the town name is intellectually enriching and, as it turns out, makes for an interesting reflection on how people understand historical figures in the present.

For me the name “Amherst” elicits very positive sentiment because of the association of a town named Amherst with many positive life experiences. But for some people the name Jeffery Amherst elicits an especially negative reaction. On November 14, 2015 while protesting against racial insensitivity and systemic racism a group of students at Amherst College came up with a list of 11 demands from the administration. Demand number 7 was:

“a statement… that condemns the inherent racist nature of the unofficial mascot, the Lord Jeff, and circulate it to the student body, faculty, alumni, and Board of Trustees. This will be followed up by the encouraged removal of all imagery including but not limited to apparel, memorabilia, facilities, etc for Amherst College and its affiliates via a phasing out process within the next year.”

Yes. For about a century the unofficial mascot of Amherst College was a caricature of Lord Jeffery Amherst. But now in the current climate of pressing social justice issues the symbolism of Lord Jeff has been officially ousted from the institution. The reason that some students see Jeffery Amherst as a symbol of “inherent racism” is interesting and underlines another tangential connection between Lord Jeffery Amherst and the Watering Place. The Quarantine Grounds that once existed at the Watering Place on the northeast shore of Staten Island was established to try to gain defensive control over infectious diseases arriving on ships. Jeffery Amherst flirted with the control of infectious disease too, but for another purpose – as a means to an end to the “Indian problem”. To many people, including the protesting students at Amherst College, Jeffery Amherst is notorious having been associated with Native American genocide and biological warfare.

Mascots are meant to bring people together by unifying a cause and facilitating a common experience. When a symbol generates division rather than unity it is no longer effective as a mascot. So Amherst College officially promised to no longer use the Lord Jeff imagery at the Institution. This makes good sense. This promise also necessitated the need to change the name of the Lord Jeff Inn in the town of Amherst because it is owned by the college. But should the college change its name too? What about the name for the Massachusetts town of Amherst?

The ability to generate automatic, long-lasting associations from experience is a fundamental property of the human and animal brain. When automatic associations form they are expressed in behavior and attitudes as stable preferences (do you prefer classical or rock music?) and biases. We all have biases that emerge from our life histories and we may or may not be aware of the automatic associations that influence them. Cognitive social psychologists label automatic associations as “implicit” when people are unaware that their attitude/behavior is influenced by them. Racial bias, for example, can be influenced by implicit associations. (To assess your own implicit associations on various topics take the Implicit Associations Tests offered by Harvard University. However, consider the web site warning seriously before proceeding with the tests.) Automatic associations are not based on deliberate rational thought, but on events that are experienced directly (i.e., private experiences) or indirectly when information is conveyed by others through language. When automatic associations emerge indirectly the information need not be accurate or factual. Advertisers and politicians know this very well; to persuade the public they often rely on emotional appeals based on incomplete, misleading, or outright erroneous information. When we become aware of owning an implicit bias and accept the bias as inappropriate or inconsistent with new gained knowledge it can be a challenge to overcome the bias especially when it concerns stereotypes and attitudes about certain groups. But it is possible to overcome recognized implicit biases acting as barriers to equality.

My subtle fondness for the name Amherst is influenced by the automatic positive associations gained from my prior experiences. But given my new gained knowledge of Lord Jeffery Amherst as a genocidal bio-terrorist should I resist and overcome the automatic association so that it is less likely to influence my thoughts, attitude, and behavior? I am sympathetic to Native Americans and I am mindful of their unfortunate mistreatment across history. I do not care to contribute to any further marginalization of this group by allowing a positive bias toward a notorious historical figure influence my thoughts and actions. Or perhaps it is the negative bias toward Amherst that should be challenged. Is the association of Jeffery Amherst with Native American genocide and bio-terroism based on incomplete or misleading information? Are Amherst’s actions from two and a half centuries ago taken out of context? Is the argument against Amherst anachronistic and based on a superficial treatment of an essentially complex historical situation? Automatic associations occur and persist in the absence of critical thought. When information is incomplete or erroneous the intellectually honest person relies on rational thought and effort to make corrections. Banning the Amherst name simply because Lord Jeffery Amherst has been alleged to have engaged in human atrocities is intellectually lazy. Ignoring reliable information that is contrary to any position on Jeffery Amherst is intellectually dishonest. A rational look at the origin of the positive and negative biases toward the Amherst name may be helpful.

Places named Amherst

1759 - A district of the town of Hadley in Massachusetts was renamed Amherst in honor of General Jeffery Amherst.

http://gedcomindex.com/Reference/Haywards/frame028.html

Amherst MA appears to be the first town with the Amherst name and is the recipient of honor bestowed by several American towns by the same name.

Chartered in 1760. Named in honor of Lord Jeffery Amherst.

http://gedcomindex.com/Reference/Haywards/frame028.html

1853 Named after Amherst Nova Scotia by Adam Uline, chairman of the town board. Also acknowledged the name as an honor to General Amherst.

http://www.pchswi.org/archives/communities/amherst/intro.html

(Note that this web site describes General Amherst of "revolutinary war fame", but he was not in America during the revolution. It should read "of French and Indian War fame")

- Named after the town of Amherst Massachusetts.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015051116740;view=1up;seq=12

About 1887. Named by the Great Northern railway most likely after the town of Amherst MA.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015027015455;view=1up;seq=79

1807. Named after Amherst county where the town is located. The county was created in 1761 and named in honor of Lord Jeffery Amherst.

http://amherstva.gov/about-amherst/town-facts/

Amherst served as crown governor of Virginia from 1759 to 1768 but he governed from England. When the rules changed requiring crown governors to be physically present in the coloniies they were governing Amherst resigned.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_colonial_governors_of_Virginia

- Named after Amherst College by a railroad official.

1818. On April 10 an act of the NY State senate created the City of Amherst NY. Why Amherst? The town may have been named in recognition of Jeffery Amherst’s achievements during the French and Indian war, but more likely it was named after the Massachusetts town [Young, S. M. (1965) A history of the town of Amherst, New York, 1818-1965, p. 21].

It is also possible that the Amherst naming was the State of New York's acknowledgment of Jeffery Amherst as a one-time owner of land in the Adirondacks. The terrain of Adirondack area made the place largely uninhabitable in the colonial times but land speculators purchased the land from the Mohawk Indians any way. In 1771 two shipbuilders from New York City requested permission to buy land in the Adirondacks (the area was in a NY county known at the time as Tyron County). The English Crown required all land purchases to be made through the Crown as a middle man for an exorbitant fee. This purchase was initiated in 1771 and is known as the “Totten & Crossfield Purchase” (these two men were front men for the actual investors hiding their identity from political rivals). The plan was to divide the land into 50 townships of 20,000 acres each to be sold to private investors. Apparently, as can be seen in this 1772 survey, Township #3 was set aside for Sir Jeffery Amherst. January 4, 1774 King George III granted to Amherst a total of 22,540 acres of land from the Totten & Crossfield Purchase.

The original land speculators and Jeffery Amherst never actually visited their land. After the American Revolution the land became New York State property. In 1785 a petition to purchase the lands as outlined in the original survey was granted. Some of the original speculators who did not flee America after the revolution were able to reclaim their investment. Curiously in a list of post-revolution land owners Sir Jeffery Amherst was still listed for Township #3.

No information available.

about 1818. The village of Amherst was named after the township where it is located which was named after Amherst, New Hampshire.

https://archive.org/stream/astandardhistor00wriggoog#page/n6/mode/2up

No information available.

1894. Named after Amherst College.

unknown date. "Named by C. A. Goodnow after old Massachusetts town."

https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=ccY1AAAAIBAJ&sjid=2RAGAAAAIBAJ&pg=487%2C2128045

1853. Named after the town of Amherst Ohio by pioneer colonist E. P. Eddy "in honor of the place in which his wife was born."

https://books.google.com/books?id=ShcLAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA190#v=onepage&q&f=false

1831 - Named after the town of Amherst, New Hampshire.

A survey of Hancock by Samuel Wasson p. 25

1764 - Named after Lord Jeffery Amherst by Joseph Morse a soldier during the French and Indian War and early settler of the town.

https://archive.org/stream/majorabnermorsee00park#page/n33/mode/2up

A tombstone in Christ Church cemetery (Amherst Nova Scotia) for Joseph Morse reads " …supply officer at Oswego 1750. Taken prisoner and sent to France, recaptured by a British Cruiser. Presented at court when King George II presented him with a sword and other marks of honour.”

In the same statement announcing the college policy to no longer use the Lord Jeff imagery the Amherst College Board of Trustees made it clear that “Amherst College will always be the name of the school”. The school after all was named after the town of Amherst, not to honor the man Lord Jeffery Amherst. There are at least 15 places named Amherst in North America. The colonial town of Amherst Massachusetts adopted its name to recognize Lord Jeffery Amherst in 1759 well before American independence. Amherst New Hampshire did the same in 1760. A town founded in Nova Scotia Canada about 1764 also honored the man who by then had captured Fort Duquesne, Fort Ticonderoga, Crown Point and Montreal from the French and had completed his military service for the British Crown in North America. Clearly these 3 towns succeeded in honoring Amherst’s name in perpetuity even though the American towns are no longer British and current residents have largely forgotten the name origin. The remaining American towns were named Amherst after America had gained its independence. Why would Americans name their town after a British general who had left the continent before the American Revolution got underway? Well in most cases, or possibly all cases, they didn’t. Amherst was adopted as the name of these various American towns because of positive personal experiences with other places named Amherst rather than in recognition of the man himself. The markers on the map above provide additional information on the name origins of these places named Amherst.

A positive view of Jeffery Amherst in the late 18th century was based largely on his role in defeating France for the English Crown in the Seven Years War. For British Canada Jeffery Amherst, like George Washington for America, is a founding father. In the United States towns named Amherst appear to have spread during the period of territorial expansion by sentimental pioneers perhaps motivated by an ideal belief in “manifest destiny”. While it is understandable that nostalgic Amherst College alumni have a fondness for the Lord Jeff mascot it is not surprising that information about the despicable actions of Jeffery Amherst toward Native Americans have led some alumni and current students to be repulsed by his caricature as a symbol of campus pride and unity. But is the information about nefarious Amherst accurate?

Information that led to a negative view of Lord Jeffery Amherst emerged over a century ago when historian Francis Parkman first introduced to the public correspondence between Lord Jeffery Amherst and Colonel Henry Bouquet concerning the defense of Fort Pitt against the Native American Indians. With the French defeated, Native Americans now living west of the Appalachian Mountains were required to shift their allegiance to a British Crown with substantially harsher policies than the French. Jeffery Amherst’s contempt for the Native Americans is well known and some of these harsher policies were put in place by him, but his attitude toward Native Americans was not unique at the time. Outraged by the new and harsher policies and the encroachment of colonial settlers into their western Native American lands a loose confederation of Indians began a resistance in 1763 known now as the Pontiac’s Rebellion or Pontiac’s War. The conflict consisted primarily of Indians attacking British forts near the western frontier. Amherst’s unsuccessful handling of the conflict reduced his prestige and he was recalled to England in 1763. It was this same year that Amherst, perhaps in desperation, suggested a plan to give smallpox-infected blankets to the Indians at Fort Pitt as evidenced by his correspondence to Colonel Henry Bouquet who was encamped near Carlisle Pennsylvania and preparing to march to Fort Pitt.

Amherst to Bouquet – “Could it not be contrived to send the Small Pox among those disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them.” (This comment is in a postscript of a letter with the first dated page missing.)

Bouquet to “His Excellency, Sir Jeffrey (sic) Amherst.” – “I will try to inoculate the ——- with some blankets that may fall into their hands, and take care not to get the disease myself.” (July 13 1763, his reply is also in a postscript.)

Amherst response to Bouquet – “You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race.”(Undated letter)

Quoted text and dates of correspondence are from Parkman (1870) p. 303-304 and footnote #303

The brief exchange in the footnotes of these letters has been repeated often and has grown into dogma that under Jeffery Amherst the British advanced American Indian genocide by successfully engaging in biological warfare with smallpox. What is the evidence that this plan was actually carried out and that it was indeed effective?

Amherst was not the only one with the deplorable idea of using smallpox as a war offensive against an enemy. According to an entry in a diary kept during the siege of Fort Pitt dated June 24, 1763 an attempt to infect the Indians with smallpox had already taken place. Two Delaware Indians, “Turtle Heart” and “Mamaltee”, approached the fort with a warning that Indian tribes were preparing to attack the fort but they were successful in stalling the attack to allow the British to abandon the fort and escape before it was too late. How did the British respond to this gesture of goodwill? To paraphrase their response: no worries we can defend ourselves. The gesture was also “rewarded” with presents of food and other items – “Out of our regard to them we gave them two Blankets and an Handkerchief out of the Small Pox Hospital. I hope it will have the desired effect.” (William Trent’s Journal at Fort Pitt, 1763, p. 400). This event at Fort Pitt was initially assumed to represent the execution of Amherst’s plan; however, this event at Fort Pitt occurred before the Amherst-Bouquet correspondence. This incorrect assumption no doubt contributed to the false and persistent view that Amherst engaged in biological warfare (Ranlet, 2000).

Interestingly the idea to use smallpox as a weapon was expressed again decades later during the American Revolutionary War (Fenn, 2002). I read from several sources that in 1777 a British officer, Robert Donkin, published in New York a little book entitled Military Collections and Remarks. In a footnote he offered a suggestion on how to deal with the American revolutionaries:

Dip arrows in matter of smallpox, and twang them at the American rebels, in order to inoculate them; This would sooner disband these stubborn, ignorant, enthusiastic savages, than any other compulsive measures. Such is their dread and fear of that disorder!

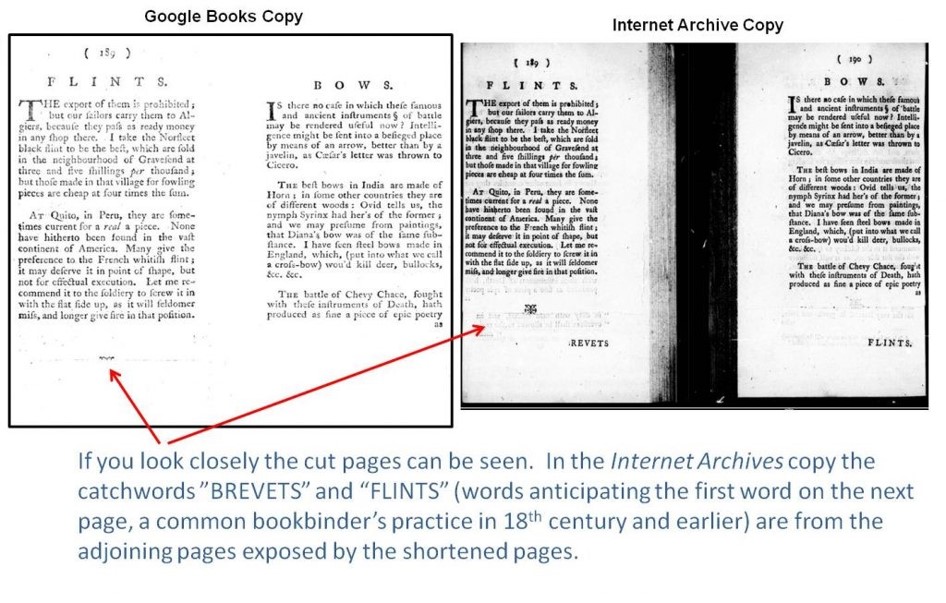

When I searched for digital copies of the Donkin book to confirm the quote I found two copies, one at the Internet Archive and another at Google Books. But I could not find the quote in either copy. Did I have the wrong book? Or is the quote a fabrication? Or perhaps I am witness to a source attribution error. With some further searching I found a book review from 1896 noting that the smallpox footnote was on page 190 but it was cut out of almost every copy of Donkin’s book (Ford, 1896). When I looked carefully at pages 189 and 190 of the two digital copies of the Donkin book it is clear that the bottom of the pages were excised. Fortunately at least one copy of the intact book was found and the missing footnote has been restored to at least one archive copy (see William L. Clements Library).

It is unknown who made the decision to excise the footnote from the book, but this action suggests that even back in the 18th century the idea of using an infectious disease as a weapon of war was a deplorable one. Although it is not clear if the idea was being suppressed on a moral basis or because of a concern that it might invoke a fear that a weapon of disease might spread uncontrollably to the general “non-savage” population. Of course these possibilities are not mutually exclusive; the post-production edit may have been motivated by both concerns.

Curiously the discussion of the Amherst smallpox blankets conspiracy often simplifies or ignores the science of infectious disease. Could the plan actually have worked? In a review of the historical and scientific evidence historian Phillip Ranlet (2000) wrote that “the smallpox incident has been blown out of all proportion, given that it was likely a total failure.” and concluded that the “time is long overdue for what happened at Fort Pitt in 1763 to be discussed rationally and on the basis of evidence rather than unsupported and repetitious assumptions.” pp. 438 – 439. In the debate about the Lord Jeff mascot two Amherst College alumni felt the need to publish a treatise not to argue against the decision to drop the Lord Jeff mascot but to point out again that the history of Lord Jeffery Amherst is much more complex than represented by his modern critics and that the germ warfare claims against him are not supported by a review of the available evidence.

John F. Kennedy Quote on Critical Thinking

Address by President John F. Kennedy, Yale University Commencement, June 11, 1962. Full speech available at https://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Research-Aids/Ready-Reference/Kennedy-Library-Fast-Facts/Yale-University-Commencement-Address.aspx

There is some evidence that people have considered the distribution of diseased agents to fight their enemies since the start of civilization and most nations with the capability to develop any weapon of mass destruction have not abstained from doing so (Frischknecht, 2002). Nevertheless in the context of the accusations of germ warfare and genocide leveled at Jeffery Amherst we should remember that these words are anachronistic. Is it fair to use these modern terms to explain 18th century European and colonial attitudes and actions toward Native Americans?

Germ warfare. Broadly defined a weapon is any means or instrument used to gain an advantage in a conflict. This definition gives little consideration of the degree of efficiency of a weapon. The specific term Germ Warfare suggests a weapon of war with some degree of efficiency. The idea shared by 18th century military leaders to use smallpox as an effective weapon of war reflected wishful thinking. It is very unlikely that smallpox blankets were effective as weapons and certainly not as weapons of mass destruction. Effective weapons are designed through a rational process. The understanding of infectious disease was woefully inadequate until the late 19th century when scientists gradually came to a consensus that germ theory was correct and when scientists learned how to further develop microbiological methods introduced by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. For several centuries prior to germ theory contagious disease was explained by the incorrect miasmatic theory of disease. A poisonous vapor called miasma was inferred from anecdotal observations as the cause of diseases such as cholera, malaria, Black Death, yellow fever and smallpox. Diseases that resulted in some form of fever were initially believed to be contagious but by the late 1700s a distinction was beginning to be made between infectious and contagious diseases (all contagious diseases are infectious, but not all infectious diseases are contagious), with Dr. Richard Bayley among the first to make this distinction (Bayley, 1798).

Here is an excerpt on miasma from an early 19th century encyclopedia:

Miasms as they relate to the diseases both of human and brute animals are productive of some of the febrile kinds and of them only as in the case of contagion. They are generally floating in the atmosphere but not observed to act except when a healthy animal approaches the sources whence they arise. The idea of contagion properly implies a matter arising from a body under disease and that of miasma a matter arising from other substances as from putrifying vegetables. . . the substances imbued with the effluvia from the bodies of the diseased may be called fomites and that it is probable that contagions as they arise from fomites are more powerful than as they arise immediately from the human body.

Good,J.M., Gregory,O. & Bosworth N. Pantologia (1819). A new (cabinet) cyclopædia, Vol VII

Fomites refer to any material believed to be contaminated with the miasma. Blankets and handkerchiefs covered with the scabs and “effluvia” of smallpox victims were feared to be powerful contagions. If Yellow Fever was prevalent during Pontiac’s rebellion rather than smallpox the blankets from the Yellow Fever hospital would no doubt be distributed by the British as the weapon of war. Belief in miasmatic theory informed this certainty. But we now know that miasmatic theory is wrong. The empirical science of germ theory tells us that our understanding of infectious disease can be complicated. Yellow fever is infectious but not contagious requiring a vector – an infected mosquito – to spread from person to person. Smallpox, however, is highly contagious and its cause, the Variola major virus, can linger on clothing and bed linens. Scabs of smallpox victims are indeed loaded with large particles containing the virus. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of contaminated linens in spreading smallpox is poor compared to direct person-to-person contact. Although smallpox was eradicated in the 1970s the fear that government stockpiles of the Variola major virus may fall in the wrong hands has resulted in a surge of smallpox studies using data from historical records, the last outbreaks in developing countries, and some laboratory experiments. According to one review of this literature (Milton, 2013) the spread of the smallpox virus in the body depends significantly on how the virus is introduced into the body. Virus particles transmitted through the skin (e.g., injection, open wound) or by inhalation more commonly results in mild virus replication in the body and mild or moderate symptoms. This may explain why the 18th century inoculation method of placing the scabs and pus of smallpox victims into a fresh incision was effective in protecting a person from contracting and dying from the disease. Poor transmission of the virus through the skin and by inhalation also suggests that smallpox blankets would not be an effective weapon for smallpox transmission. The most effective mode of transmission of the smallpox virus appears to be the normal breathing of smallpox victims. While breathing finer particles of virus-laden droplets from the lungs of smallpox victims spray into the air and by virtue of their small size may linger there for many hours.

There is no evidence that Amherst’s suggestion to Bouquet was ever executed. Even if it was, it is very unlikely that it would have worked. The spread of smallpox that occurred among the Native Americans near Fort Pitt and elsewhere was more likely due to close interactions with contagious British soldiers and American Indians than with any fomites. Despite their lack of efficiency smallpox “weapons” in the 18th century could have been effective as weapons to terrorize people or to intimidate soldiers; the latter appears to have been the intent in Donkin’s excised footnote. Indeed even today the argument has been made to classify biological weapons, which continue to be largely inefficient, as weapons of terror/intimidation rather than as weapons of mass destruction (Harigel, 2001; Panofsky, 1998).

Genocide. Yet Jeffery Amherst did have the idea to use smallpox for what he believed to be an effective weapon of war against the tribes of Native American Indians. The British and American treatment of Native Americans fit Raphael Lemkin’s definition of genocide. It was Lemkin who coined the word in 1944 as “an old practice in its modern development.” The word was adopted at the 1948 United Nations General Assembly as reflecting many crimes against humanity that was perpetrated in many historical periods and it was at this assembly that genocide was defined for the first time as an international crime. The modern discussion of genocide is not uncomplicated, however, and has generated an abundance of scholarly debate and publications. There are scholarly journals on the topic as well as many academic centers for the study of genocide such as the program at Rutgers Newark where Raphael Lemkin once taught law.

Was Jeffery Amherst planning the genocide of American Indians? He did, after all, use the related word “extirpate” in his correspondence to Bouquet and there is some evidence that many Native American Indians were fearful of their complete physical destruction by the British and later the American governments (Ostler, 2015). An informed opinion is appropriate here. In forming our opinion we need to also consider whether we would expect the man Amherst as a leader of his day to have risen above the prevailing attitudes of his time.

References

Bayles,R.M. (1887). History of Richmond County, (Staten Island) New York, From its discovery to the present time. New York: I. E. Preston & Co.

Bayley, R . (1796). An account of the epidemic fever which prevailed in the city of New York, during part of the summer and fall of 1795. New York: T. and J. Swords.

Donkin, Robert. Military Collections and Remarks. [Three Lines from Tortenson] Published by Major Donkin. Printed by H. Gaine, at the Bible and Crown, in Hanover-Square, 1777.

Ford, P. L. (1896). Reviewed Work: Sketches of Printers and Printing in Colonial New York by Charles R. Hildeburn. The American Historical Review, 1(3), 547-549.

Frischknecht, F. (2003). The history of biological warfare, EMBO Reports, 4(Suppl 1): S47–S52. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor849

Good, J.M., Gregory, O. & Bosworth, N. (1819). Pantologia. A new cabinet cyclopædia, Vol VII, LHW – MID. London: J. Walker.

Harigel, G.G. (2001, November 22). Chemical and biological weapons: Use in warfare, impact on society and environment. Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.wagingpeace.org/chemical-and-biological-weapons-use-in-warfare-impact-on-society-and-environment/.

Lemkin, R. (1944). Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation – Analysis of Government – Proposals for Redress. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Milton, D. K. (2013). What was the primary mode of smallpox transmission? Implications for biodefense. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2, 1-7. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2012.00150

Ostler, J. (2015). “To Extirpate the Indians”: An Indigenous Consciousness of Genocide in the Ohio Valley and Lower Great Lakes, 1750s–1810. The William and Mary Quarterly, 72(4), 587-622.

Panofsky, W.K.H (1998, April 1) Dismantling the concept of ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’ [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.armscontrol.org/act/1998_04/wkhp98

Parkman, Francis (1870). The conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian war after the conquest of Canada, Vol. 1,6th Edition, Boston : Little, Brown and company.

Ranlet, P. (2000). The British, the Indians, and smallpox: What actually happened at Fort Pitt in 1763? Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, 67(3), 427-441.

Sweeney, K. (2008, Fall). The very model of a modern major general. Amherst Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.amherst.edu/amherst-story/magazine/issues/2008fall/lordjeff.