Like Father Like Daughter: The Relationship of Dr. Richard Bayley and Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton

Engraving portrait of Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton around the age of 22 with French caption, after a 1796 portrait (Notre Dame Archives).

On August 11th 1796, Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton wrote a letter to her friend Eliza Sadler describing her father, Dr. Richard Bayley:

My Father is Health officer of New York and runs down in his Boat very often to see us, and when he meets me and little love he says there never was such a pair, that he sees no such cheerful welcome expression in any other eyes in the world–You may believe it for there never was truer affection in any Heart than in Mine towards him. (12)

Here, Elizabeth not only makes her affection for her father evident, but she also identifies him immediately as the “Health officer of New York.” Before describing her father’s demeanor or his gladness at her greeting, she first identifies him with his profession as a physician; indeed, it seems that Elizabeth’s relationship with her father was extremely affected by her father’s work. When Elizabeth was a young girl, Dr. Bayley was frequently absent because of his studies in medicine; when she was thirteen, the Doctor’s Riot branded itself into her memory; when she was an adult, she would visit him where he lived at the Quarantine Grounds and observe him helping the sick immigrants there. Over the years, they formed a bond which was, in many ways, shaped by Dr. Bayley’s involvement in medicine, and which most likely inspired Elizabeth’s own work with the poor and sick. As Joseph I. Dirvin puts it in his biography of Elizabeth, “of all of his children, Richard Bayley seemed most attached to Elizabeth. Perhaps she best understood him and the love of medicine that drove him so mercilessly. There can be no doubt that Elizabeth and her father were kindred souls, the same love of life, the same heart for the poor, the same delight in culture and letters” (4).

Elizabeth’s affection for her father, and her view of him as a doctor, is seen best through a portraiture of him written in her handwriting that was found among her papers:

His voice is peculiarly adapted to cheer the desponding and encourage the trembling sufferer, who shrinks with fastidious delicacy from any of the remedies of the healing art. Nor is its influence less salutary to the being who, shaken by the tempests of the world, yet struggles to brave them, and support a claim to reason and fortitude. Nature has endowed him with that quick sensibility by which, without any previous study, he enters into every character, and the tender interest he takes in the mind’s pains as well as the body’s, soon unlocks its inmost recesses to his view, and fits it to receive the species of consolation best adapted to its wants. It may be said of him, as of the celebrated and unfortunate Zimmerman, that he never visited a patient without making a friend. (547)

While the original copy of this description cannot be recovered, it is not difficult to believe that Elizabeth would have written such a portrait of Dr. Richard Bayley, since she so often viewed her father through the lens of his profession; Dr. Bayley was so devoted to his work that, for Elizabeth, his personality and many of his traits became almost synonymous with his identity as a physician. She describes his voice as suited specifically for his work with the sick, since it “is peculiarly adapted to cheer the desponding and encourage the trembling sufferer,” and she claims his “quick sensibility” and his friendliness as also particularly suited for his work. Thus, for Elizabeth, it seems that Dr. Richard Bayley was always a doctor first.

Absence and Study

Elizabeth had good reason to see her father as synonymous with his work, since his obsession with medicine and devotion to his discoveries very dramatically affected her in her childhood. Especially in her younger years, Dr. Bayley seemed to be so devoted to his work that it made him act irresponsibly with regards to his family. He left to study in England only a few short months after Elizabeth was born to study anatomy with the famous anatomist and surgeon Dr. William Hunter, and was absent for four of his eight years of marriage to Elizabeth’s mother, Catherine Charlton; indeed, “shortly after his marriage” to Catherine, “it became obvious that medicine was the real love of Richard Bayley’s life” (Dirvin 5). After Catherine died, when Dr. Bayley got remarried to Charlotte Amelia Barclay in June of 1778, his will (drawn in 1788) left everything to Charlotte and her children, completely cutting off his daughters from his first marriage, Mary and Elizabeth (12). He was continually absent from the lives of his wife and children, and his absence affected Elizabeth dramatically. Elizabeth was often lonely as a child and adolescent, so much so that, when her father passed by her school on his way to make doctor’s calls, she would rush out of her class to kiss him, “a lonely little girl assuring herself of somebody’s love” (13). In late 1788, when Elizabeth was in her early teen years, Richard Bayley left for England again, and “this absence of her father was harder on Betty than any of the others had been, for she never heard from him in all the time he was away, well over a year” (21). His absence shook her self-esteem, and worried her, for she lived day to day “not knowing whether her father was alive or dead, but certain that she had lost him and that he had no care or concern for her” (22). Dr. Richard Bayley’s only obvious care and concern was for his work, and so he ironically caused those closest to him to suffer in a way that could not be cured by medicine.

Doctor’s Riot

Elizabeth was thirteen on April 14th 1788 when the Doctor’s Riot tore through the streets of New York, demanding proof that her father and others who worked with him were not working with human cadavers in their experiments and studies. The mob that formed on the second day of the riot “had a definite purpose: to search the homes of the suspecting doctors, including, of course, the home of Dr. Bayley, where Betty and her family sat in dread” (20). In this moment, perhaps, Elizabeth understood in some new way the stakes of her father’s work, and the impact he was having. What passed through her mind as she sat, terrified of the people who were marching the streets in search of her father? What must she have thought of him, and of his work, because of it?

Letters

By the year 1790, Elizabeth was no longer welcome in the home of her father and stepmother because of a “family disagreement” (28), and so she was reduced to asking for charity from her friends between 1790 and 1794 for a roof overhead and food. It was during this time that she actually mended her relationship with her father, and formed a deeper relationship between them, through letters. Dirvin writes, in his summary of the nature of their letters:

There was now a great rapport between them. They were after all very much alike, but it seems to have taken the good doctor all these years to discover it. The rapport was genuine. It was based on mutual understanding and recognition. Betty truly understood, for instance, that Richard Bayley’s lack of success as a husband and a father was due in great part to his complete absorption in medicine and his compelling desire to serve mankind. (29).

Richard Bayley seemed to go through a personal transformation because of this newfound relationship with his daughter. His previous periods of absence were remunerated by his reliance on her for his confidence, remaining in constant contact and asking her for advice. Indeed, this correspondence between father and daughter became so vital to both that, if Dr. Bayley were out of the city on business, he expected a letter every day (30), and Elizabeth’s letters to her father reveal how intent she was on keeping in contact, and how apologetic she was for neglecting to write. The Doctor and his daughter were beginning to make amends.

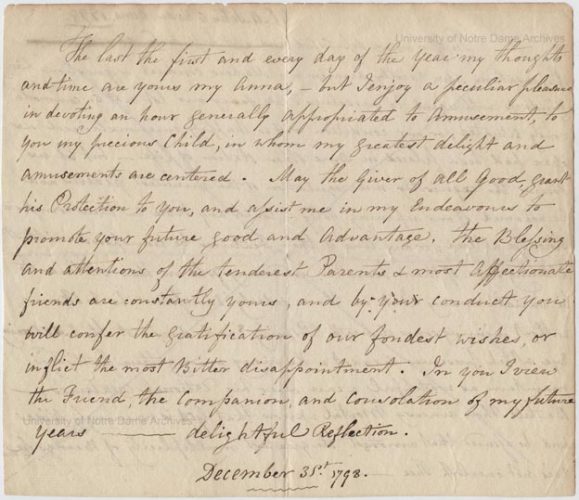

“In her own handwriting”: Letter from Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton to her daughter Anna Seton, 12/31/1798 (Notre Dame Archives).

Quarantine

In May of 1801, Elizabeth and her husband and their children moved to the Battery in New York City – 8 State Street, now the sight of The Church of the Holy Rosary. This proximity to Staten Island enabled her to have more direct contact with her father’s work in the Quarantine Station. Richard Bayley himself had lived down the street at 5 State Street before he had moved to Staten Island do his work at the Quarantine in 1799. At the Quarantine, he worked from three in the morning until long after the sun had set, while Elizabeth watched for his “infrequent visits to the house, ready to drop everything and bring him a moment’s comfort” (91). Elizabeth herself would even visit the Quarantine from time to time, and observed the desolation (and the faith) of the immigrants who came there. In her letters to her friend Julia, she recounted the “scenes of desolation and suffering” that occurred there, and the way she was affected by them: “to me who possesses a frame of fibers strong and nerves well strung, it is but a passing scene of nature’s sufferings, which when closed will lead to happier scenes” (as qt. in Dirvin 90). Elizabeth was moved by the faith of these suffer sick and poor, as they staggered from the ships and fell to their knees, kissing the ground and crying out prayers of thanksgiving for their safety (91). Perhaps, in these moments, Elizabeth understood with tremendous clarity the importance of her father’s work, and admired his utmost devotion to these people who needed him so badly.

Death

Of course, it was this devotion that brought Dr. Richard Bayley to his grave. On August 9th 1801, an immigrant Irish ship sailed in, and Dr. Bayley performed his duty as State port officer, only to contract an infectious disease from the passengers. As Elizabeth describes to her friend Julia in a letter written a month later, on August 10th Dr. Bayley went to bed fine, on the morning of the 11th he came down with the symptoms. Elizabeth recounts the incident:

In the Afternoon My Father was seated at his Dining-room window composed, cheerful and particularly delighted with the scene of shipping and manoeuvering of the Pilots etc., which was heightened by a beautiful sunset and the view of a bright rainbow which was extended immediately Over the Bay- He called me to observe the different shades of the sun on the clover field before the door and repeatedly exclaimed “in my life I never saw anything so beautiful” – little Kit was playing in my arms and he pleased himself with feeding her with a spoon from his glass of drink and making her say papa-after tea I played all his favourite music and he sung two German Hymns and the Soldiers Adieu with such earnestness and energy of manner that even the servants observed how much more cheerful he was than any Evening before, this summer – at ten (an hour later than usual) he went to his room and the next morning when Breakfast was ready (tho’ it was then but just sunrise) his servant said he had been out since daylight and just returned home very sick. He took his cup of tea in silence which I was accustomed to and went to the wharf and to visit the surrounding buildings. Shortly after he was sitting on a log on the wharf, his head leaning on his hands exposed to the hottest sun I have felt this summer and looked so distressed as to throw me immediately in a flood of tears (which is very unusual for me) the umbrella was sent and when he came in he said his legs gave way under him went to bed and was immediately delirious. (185)

In this letter, Elizabeth primarily remembers her father’s interactions with her and her daughter Kit, as he looked out at the sunset and taught his granddaughter how to say “papa.” In a significant moment of reversal, Elizabeth’s posthumous descriptions of her father give primarily place to his identity as her father and the grandfather of her children, and not his identity as “Health officer of New York.” Then, on August 17, less than a week after contracting the disease, Dr. Richard Bayley died holding Elizabeth’s hand. As she describes it: “he struggled in extreme pain until about 1/2 past two Monday afternoon the 17th, when he became apparently perfectly easy, put his hand in mine turned on his side and sobbed out the last of life without the smallest struggle, groan, or appearance of pain” (186). Although his body was wracked with the illness he had spent his life combatting, Dr. Richard Bayley died peacefully, holding the hand of the daughter whom had become so precious to him.

In 1803 Elizabeth and her family moved out of 8 State Street and set sail for a trip to Italy in the fall. Before leaving the house, Elizabeth paid a “last visit to Staten Island and the Quarantine,” and went to stand in the place where she had last seen her father alive (Melville 79). On the 20th of September in 1803, Elizabeth writes to Eliza Sadler: “I had an unlooked for enjoyment last Thursday-Walked thro’ the Quarantine garden and trod that wharf’s every plank of which His feet had been on. Sailed over the Bay in His Boat alone” (220). For Elizabeth, it was in this place – the Quarantine – that he was most present to her; once again, Richard Bayley was synonymous with his medicinal work and his devotion to the sick immigrants.

Miranda Lynn Hajduk

Seton Hall University English MA Program

Works Cited

Dirvin, Joseph I. Mrs. Seton: Foundress of the American Sisters of Charity. Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, Inc., 1962.

Melville, Annabelle M. Elizabeth Bayley Seton 1774-1821. Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s, Inc., 2009.

Notre Dame Archives. March 23, 2011 http://www.archives.nd.edu/about/news/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/GSET-01-00-01.jpg. Accessed 7 December 2017.

Seton, Elizabeth Ann. Collected Writings: Volume 1, edited by Regina Bechtle, S.C and Judith Metz, S.C. New City Press, 2000. Vincentian Digital Books, http://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/9. Accessed 7 December 2017.