Focus on Miracle Workers: The Barber of Larkana

Madison Feser

Staff Writer

Pakistan has an epidemic that leaves tens of thousands of children vulnerable and alone. Bandits known as “dacoits” kidnap children for ransom money, and in rural provinces like Larkana, local law enforcement is practically powerless.

Fida Hussain Chandio, deputy superintendent of the city police, laments that interrogation techniques do not always lead kidnappers to reveal the identity of their victims; and traumatized children, recovering from the ordeal of kidnapping and often physical and sexual abuse, are not always keen on speaking with uniformed officers. “There are things we police cannot do”, Chandio told the The Guardian. “[There are things] that children will only admit to an old man, like Uncle here.”

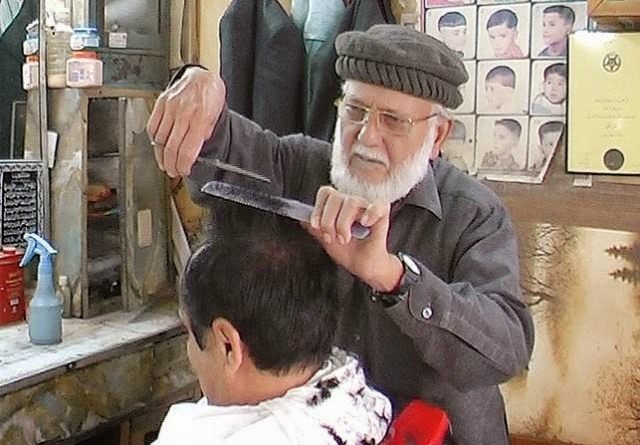

That old man, that Uncle, is none other than 75-year-old Anwar Khokhar, better known as the Barber of Larkana. A barber by trade, Khokhar’s skills earned him a valuable position as personal barber to Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his family. His barber skills, however, are nothing compared to his reputation as a rescuer of lost children; making Khokhar a beacon of hope for his community.

As a volunteer at the Qaim Shah Bukhari shrine in 1988, a shrine located next to his barbershop, Khokhar first encountered lost and runaway children. To find their families he began by walking through the street with signs, yelling out the children’s names on a loudspeaker.

His mission has expanded since then, and in 2001 the Pakistan People’s Party donated land at Airport Road so Khokhar could build the Khidmat-i-Masoom Welfare Trust. The shelter mostly serves children and young adults, but the homeless and elderly are increasingly seeking refuge at the home, reports Dawn. As of 2017, Khokhar has reunited 11,000 lost or kidnapped children with their families since beginning his work, according to Pakistan Today.

“I am like a fish out of water”, he told BBC. “If you pull me out of my work with these children, I will die.”

Some of his cases are easy, with families reunited within hours. Unfortunately, other cases take years. One girl lived with Khokhar and his wife, who have eight children of their own, for seven years before they found her family, Khokhar told BBC. Cases become especially tricky when they involve girls who flee arranged marriages. To protect these girls from honor killings, police place an armed guard at the shelter and Khokhar and his wife even ask courts for legal custody over them, reports the Guardian.

These missions are often dangerous. Children either find Khokhar, or police officers place children into his care; however, there are also times when frantic parents enlist his help in finding their missing kids. In these instances, Khokhar does not back down. Once, he and a friend snuck into a dacoit camp to recover two children, only to uncover a forced labor camp filled with at least 100 children and young adults, reports BBC.

To keep track of the children, even after their families claim them, Khokhar keeps files of each case, including pictures of the kids, letters of gratitude from their families, abduction reports, and newspaper articles, reports the Guardian. Upon claiming a child, adults must even provide a thumbprint and a copy of their national identity card.

Khokhar receives about 11,000 rupees a month from philanthropic organizations, but the center costs about 50,000 rupees a month to operate, reports Dawn. Despite this, Khokhar has no plans of ending his work and even hopes to open another center in a different part of Larkana.

Although he has had to put his career as a barber to the side, even converting his barbershop into an outreach office, Khokhar continues serving the Bhutto family. Their generous payments provide him and his wife with the financial means to care for not only their children, but also the children they rescue.

Fast approaching 80 years old, many wonder if the Barber of Larkana will step down and lead a quite retirement. For this miracle worker, the idea is unthinkable. “After retirement, people usually grow a beard and sit in a corner of the mosque to please God,” he told The Guardian. “But I believe that to serve humanity is the biggest way to please God. I cannot retire.”

Even when Khokhar is unable to continue his work, his legacy, it seems, will live on in his son Younis Ali Khokhar, whom Khokhar has prepared to carry on the mission.