By Molly Petrilla

The undefeated Pirates had already stomped Xavier University in the semifinals, shutting them out 4-0. Now the BIG EAST championship title rode on a final best-of-seven-games showdown against DePaul. Six games in, the schools were tied. Well into the seventh game, they were tied again. It would all come down to the final few seconds.

It’s the classic sports moment — a nail-biting final, the result of hours of training, and a last-second goal (in this case, DePaul’s) to win the game. But there was an added twist to this particular matchup: the players were sitting at computers inside a New York City gaming lounge, and their sport was a video game called “Rocket League.”

Between dedicated club members, the recent launch of BIG EAST esports tournaments, and the University’s new computer lab/esports facility in Jubilee Hall, Seton Hall has officially entered the world of competitive video gaming — and its teams are emerging as serious, conference-leading competitors.

While video games and competitions around them date back to the 1970s, esports — team-based competitive video gaming that mirrors traditional sports competitions — have risen to prominence in the past decade. And it’s been a rocketing ascent. The global esports market was expected to generate $1.1 billion in revenue last year, more than double from just three years ago, according to the analytics company Newzoo.

In 2018, more people watched the “League of Legends” World Championship than the 2019 Super Bowl. And in July 2019, a 16-year-old from Pennsylvania took home $3 million for winning the Fortnite World Cup Finals.

“This is no longer a trend,” notes Paul Fisher, Seton Hall’s associate chief information officer. “It’s now an industry — and we need to look at it as such from an educational perspective, from a management perspective, and certainly from a business perspective.”

“We have an opportunity here at Seton Hall to harness what’s happening,” he adds.

From Fledging Club to BIG EAST Champs

When he wasn’t in class or studying for exams, Victor Gomez ’17 spent most of his time at Seton Hall either managing the school’s first esports team or trying to help others understand why competitive video gaming belonged on campus.

“Basically anyone who would listen would get a miniature presentation on Seton Hall esports,” he says now.

Aside from turning himself into a walking Wikipedia entry on the history and statistics behind esports, Gomez personally understood their broad appeal. He’d gotten hooked on playing competitive “World of Warcraft” in high school and discovered the game “League of Legends” at Seton Hall.

“It was like when I was playing volleyball or running track or playing soccer — that feeling of, I want to improve because I know I could win if I just fix this one thing,” he says. He also loved the camaraderie among teammates and the way winning relied on strong communication.

“It was like when I was playing volleyball or running track or playing soccer — that feeling of, I want to improve because I know I could win if I just fix this one thing,” he says. He also loved the camaraderie among teammates and the way winning relied on strong communication.

The Seton Hall Gaming Sector club was less than a year old when Gomez joined in 2013 — the same year that the United States officially recognized esports players as professional athletes. Esports were beginning to explode on campuses around the country, and Seton Hall’s teams started training to compete and entering regional tournaments.

A high point for Gomez came in 2015, when Riot Games flew him and Joshua Caruso ’16 out to Santa Monica for a “League of Legends” Collegiate Summit. Gomez offered the company his opinions, talked about the gaming scene on campus, and “played a lot of video games,” he remembers. He says Seton Hall was one of just 75 schools selected to attend the summit, and the only one from New Jersey.

Still, the Seton Hall esports teams ebbed and flowed. Some years they were highly competitive. Others, more lax. And while the gaming club itself grew to 250 members in 2015, with up to 70 students playing “League of Legends” alone, “there was definitely a population we weren’t reaching,” Gomez says.

When Christian Ciardiello, now a senior, joined the club in 2016, he set out to strengthen the teams — not as a player, but by managing them. A former varsity athlete in soccer and track and longtime video game enthusiast, Ciardiello counts himself among the hundreds of millions of people who don’t compete in esports, but love to watch them.

“Professional players in the NFL, NBA, MLB — they’re not simply good at what they do, but in a way they’re also entertainers,” he says. “People love watching people who are really good at things they’re passionate about. It’s the same with esports.”

As esports manager, Ciardiello devoted himself to assembling strong player rosters, scheduling practice scrimmages with other schools, and placing the teams into leagues and tournaments.

Today the Seton Hall esports teams practice together eight hours a week. A student coach doles out training assignments. The players review videos of their past matchups to spot mistakes and areas for improvement.

The result has been a growing list of achievements — including, in 2018, when Seton Hall won the inaugural Electronic Sports League (ESL) BIG EAST Esports Invitational for the game “Rocket League.”

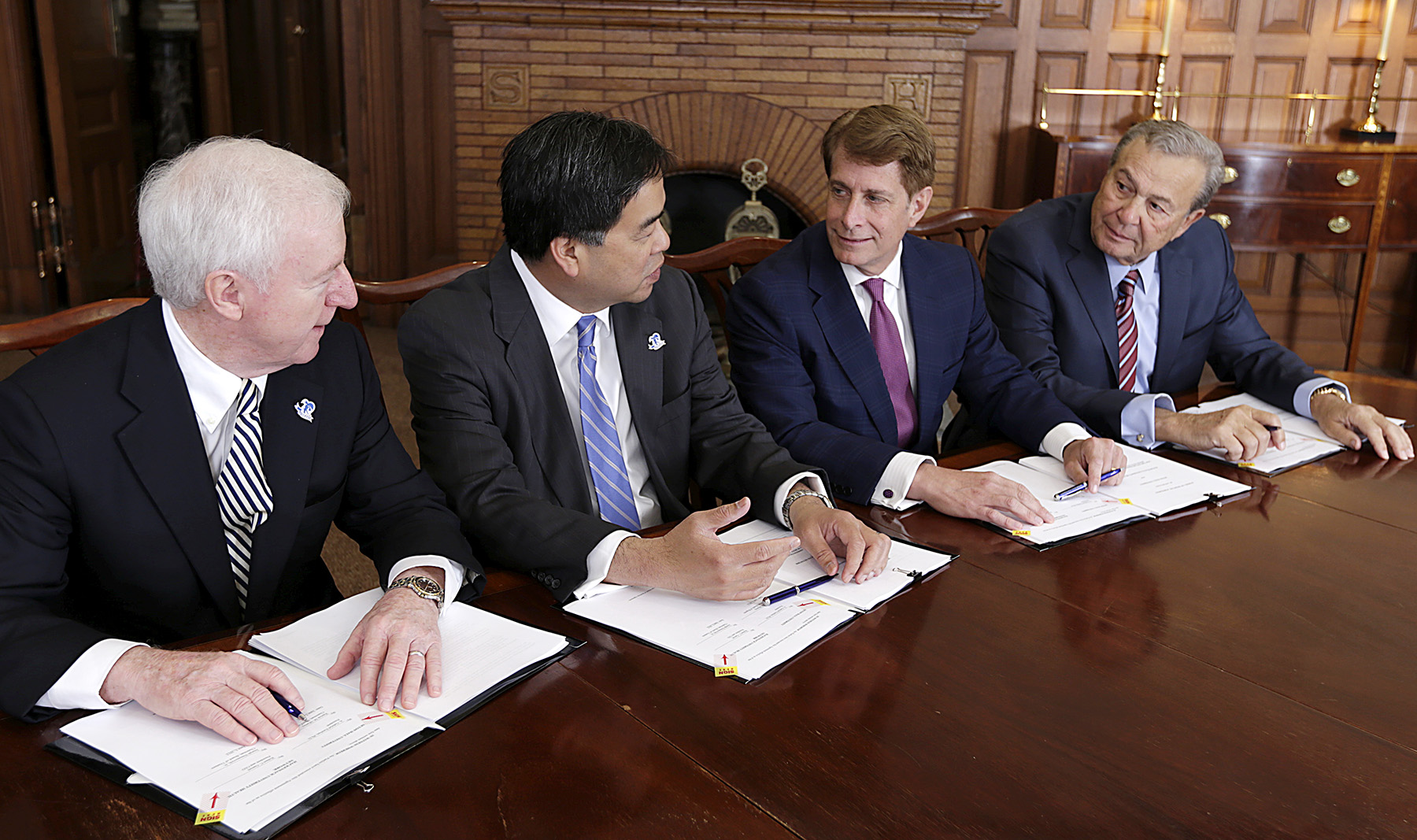

Fisher says that the pilot BIG EAST season in 2018 showed that the conference was starting to take competitive video gaming seriously. And in March 2019, the commitment further crystallized when leaders invited Fisher and other CIOs from BIG EAST schools to conference headquarters to talk about collegiate esports.

“I came back from that meeting and started digging in, asking, ‘What is this all about?,’” Fisher remembers. He met with Ciardiello and talked to Gomez, who had returned to campus in 2018 as both adviser of the Seton Hall gaming club and an assistant director of scheduling/operations for the student life department.

Fisher surveyed the Seton Hall campus about esports and was shocked by the results: 67 percent of undergraduates said they wouldn’t go to a traditional sporting event, but they would go to an esports event.

“How do we leave that kind of engagement on the table?” he says. “Why wouldn’t we start investing in getting that 67 percent of students engaged in a University-supported program — getting out of their rooms, getting them in leadership roles and social roles, and playing the games as part of a team?”

IT had plans to renovate a computer lab in Jubilee Hall, and Fisher pitched the idea of designing it specifically for esports. With input from Gomez and Ciardiello, the space has become the first official esports facility on campus, with high-power PCs, gaming chairs, and consoles including Microsoft Xbox One and Nintendo Switch. Though open to all students, the gaming lab is now the teams’ home base for practices and matches.

Gomez’s reaction to the new spot? “In a word? Amazing,” he says. “I see it as a victory not only for myself and my current students, but for anyone who’s been a part of [Seton Hall esports] since day one — and even those who are only recently discovering our existence.”

More Than Games

Seton Hall isn’t the only university embracing esports right now. The National Association of Collegiate Esports counts more than 170 schools as members — a number that’s already double what it was just two years ago. (And that doesn’t include the dozens of club teams, like Seton Hall’s, which are not yet varsity teams as NACE requires, but still practice, compete and win.)

The Ohio State University and several other schools have rolled out undergraduate majors in esports.

The University of California, Irvine unveiled a 3,500-square-foot UCI Esports Arena. And in 2018, Harrisburg University in Pennsylvania became the first college esports program to award full scholarships to its entire 16-player roster.

Collegiate esports players can also land scholarship money through tournaments. Ciardiello says the Seton Hall “Rocket League” team is already on track to earn “a little bit of money” this spring through competitive play. He’s hopeful that those numbers will grow in the future.

“Most students get scholarships through academics or through athletics,” he notes. “A lot of players on our teams — the thing they’re really good at is video games. They know the games as well as someone knows a specific subject or an athlete knows how to play their sport. There are more than enough opportunities in the collegiate esports world for these students to earn scholarship money to help pay for college.”

There are nonfinancial benefits, too. Gomez sees the Seton Hall esports teams as a potential source of both student recruitment and retention. He says they’re a place where game lovers can find a sense of community. “There’s also a lot of space for diversity,” he adds. “In a video game, it’s only about what’s on the screen and how good you are. If you don’t want to, you don’t even have to speak. No one’s looking at you directly. A lot of times, people can find it to be very liberating.”

And as the new degree programs illustrate, collegiate esports is a passion that can flow straight into a career. According to Indeed.com, job postings for esports roles increased by 11 percent in 2019. “Just think of all the careers around this billion-dollar industry that’s coming to fruition,” Fisher says, listing jobs like event planning, marketing, social media direction, sports management, and even athletic training for gaming injuries — not to mention professional gamer careers.

The Seton Hall teams offer “a huge opportunity to engage our students and get them into careers they have a passion for,” he adds.

Bryan D’Imperio ’16 started playing “Super Smash Bros.” his freshman year at Seton Hall, when Hurricane Sandy swept through the state and confined students to their dorms. He eventually joined the Seton Hall Gaming Sector and developed a zeal for competition.

“I felt this drive to keep getting better and better,” he says. “Anytime a new person would come in and beat me, it would light a fire under me. I loved being able to push myself farther and farther.”

Today D’Imperio works as the director of social media and brand content for Will2Win Gaming, a team founded by fellow Seton Hall graduate Brien Latumbo ’15. A career in esports is “never something I imagined when I started playing,” D’Imperio says, “but now there are so many opportunities to get into a team or even make your own.”

Esports experience can translate in subtler ways, too. Though he has never played with the team, Ciardiello says he refined his leadership skills as esports manager and president of the gaming club. After he graduates with a bachelor’s degree in accounting and a certificate in information technology management this spring, he’ll begin an internship with PricewaterhouseCoopers.

“Every single time I had an interview with any firm, I’d talk briefly about my academics and classes,” he says, “but most of the time, it was focused on esports.”

Leveling Up

Esports show no signs of fading anytime soon. A report from Business Insider Intelligence predicts that by 2023, 600 million people will be watching esports. In Philadelphia, Comcast is building a $50 million esports arena, set to open in early 2021.

As competitive video gaming continues to sweep through the sports world, Fisher also sees its potential to expand further at Seton Hall. In early 2020, he plans to bring together students, faculty and administrative leaders to explore how esports might grow at the

University.

As the winter tournament season wrapped up, Gomez, Ciardiello and the Pirate esports athletes were already looking toward their next matchups — including games through the ESL Collegiate BIG EAST “League of Legends” Invitational and the Collegiate Rocket League.

“At the end of the day, this is very new not only to the University, but to every university both domestically and abroad,” Gomez says. “And we’re excited to see how far our Seton Hall teams can go.”