The long road to Seton Hall started for each of them in a distant village, with a devout family and a religious superior who saw a seed that would be better nourished in a field far from home.

For Father Khoa Le it was on the small piece of land where his parents grew rice in Hue, Vietnam, a nation where Catholics make up just 7 percent of the population but three of his uncles and one of his brothers are priests. When he was ordained three years ago he came to be known as Father Matthew, after his baptismal name. “Then my bishop sent me here to study,” he says. He started work in September toward a master’s degree in pastoral ministry at Immaculate Conception Seminary.

For Sister Marie Therese Nguyen, it was also in Vietnam, amid the coffee and pepper trees her family tended farther south in Dak Lak. Four of her aunts are sisters, two of her uncles are priests, and one of her brothers is a seminarian. “My superior asked me to come,” says Sister Marie Therese, whose given name is Linh Thi Khanh Nguyen and who is studying for a bachelor’s degree in Catholic theology. “I refused the first time, because I thought that I did not have the ability to learn English, and because America was unknown and everything was new. My superior asked me to pray. I obeyed her and followed God’s plan.”

For Sister Magdalena Chubwa, religious life started in western Tanzania, in a small mud-walled church in Nguruka where the Missionaries of Africa came to celebrate Mass once a month. “We heard there is this kind of life, this religious life, but we were just imagining what it means to be a sister because we never saw one before,” says Sister Magdalena, who is working toward a Ph.D. in health sciences at the School of Health and Medical Sciences. “You just get attracted to praying and helping people. You just get attracted with this idea that I’m going to be somebody different from other girls.”

They came to Seton Hall through a small but hopeful effort by the University to open its doors to professed religious students (those who have taken oaths or have been ordained) who can learn more here than their home countries can teach them — and who can then return to spread what they’ve learned. “I think it’s important because the Catholic Church is worldwide, and one of the blessings of the United States is that we have resources to be able to assist people as brothers and sisters in the faith,” says Monsignor Joseph Reilly, the seminary’s rector. “I think it’s part of who we are as Catholics to serve the universal mission of the Church.”

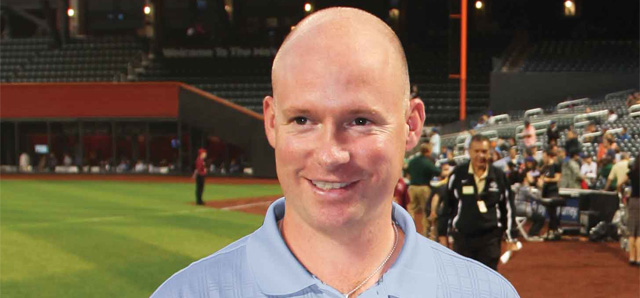

Sister Magdalena arrived first, in 2016, on a scholarship to the doctoral program. Sister Marie Therese and Father Matthew arrived at the start of the fall 2018 semester, their scholarships funded by a new program tentatively called “Bound By Love,” a name derived from the hymn “In Christ There is No East or West.” “We were faced with what we were going to call this new initiative,” says Michael Burt, senior director of seminary development, who was at Mass with Monsignor Reilly when one line from the hymn struck them both: “One great family bound by love throughout the whole wide earth.” “When we heard that line, it jumped out at us.”

In Father Matthew’s home village, Christmas is for most people just another day of work and school, as it is in all of Vietnam. “We could go to church, but some activities were limited,” he says about growing up Catholic there. The seminary in Hue that his uncles had attended was closed at the end of the Vietnam War, when a communist government took control of the whole country.

He knew early on that he wanted to become a priest, and he spent his summers at the parish where one of his uncles was pastor. After earning a university degree in mathematics, he went to the seminary in Hue, which had reopened in 1994. Less than a year after his ordination he was on his way to America.

His bishop said, “I’d like to see this man study theology,” Monsignor Reilly says.

Father Matthew’s first stop was in Houston, with a Vietnamese-American priest who worked with the Archdiocese of Hue, and who had been a classmate of Monsignor Reilly’s at Seton Hall’s undergraduate seminary. He learned English there, and how to drive, before coming to New Jersey. “It’s harder here than in Houston,” he says about driving. “In Houston the roads are wider and straighter.”

He has been navigating the roads between South Orange and Hillside, where he is living at Christ the King Parish, and celebrating Mass for smaller groups than he did in Vietnam.

Three days a week he is in classes at the seminary. “I learned not only knowledge but the way they are enthusiastic to teach,” he says about his professors. “My classmates help me if I don’t catch everything.”

He may end up a teacher himself at his home seminary in Hue when he returns. “I think I will have some new knowledge and some new vision to help them,” he says. “There is a way to give them what I experienced here, especially the generosity. That is the first and deepest feeling I got when I came here — the generosity and charity people have to reach out to others.”

Sister Marie Therese was just 12 when she left her family to live with a group of religious sisters who could educate her in ways that the public schools of a communist nation could not. “I think my parents had a purpose and wanted me to be a sister,” she says. “My uncles, my aunts — they followed the call. That’s why my parents encouraged me to do so.”

When she was 18 she traveled 12 hours by bus to join the community her aunts belonged to: the Sisters of Providence of Portieux. She ministered to the poor and the sick, and was chosen by her superior to continue her education at Assumption College for Sisters in Mendham, New Jersey, a small school for women with religious vocations. “I liked working with people in the parish, and I did not want to leave those things and go to America where I did not know anything,” she says. “I failed the first visa interview and I was so happy, but I got the visa the second time.”

She excelled at Assumption, earning an associate’s degree, and caught the attention of Sister Maria Pascuzzi, associate dean for undergraduate studies at the Seminary School of Theology. “I said, ‘give me your best student, let her apply and see how much of an academic scholarship she gets,’” says Sister Maria, who found enough funding for Sister Marie Therese, including some from her own order, the Sisters of St. Joseph. She also found housing for her at the Sisters of Charity motherhouse in Convent Station, where Sister Magdalena also lives.

“I look at her as kind of a forerunner of the possibility of religious women from other parts of the world coming and having an international experience of education that enriches their evangelization prospects,” says Sister Maria, who would like to establish a small community of international sisters studying theology at the University. “She’ll go back to Vietnam having had an opportunity for a pretty rigorous and intellectually challenging degree in theology. She’s going to bring this degree both into her religious community as a source of enrichment and formation and then go into the mountains and do pastoral work and be able to speak as a mature, intelligent, well-trained woman who can go out and evangelize.”

Sister Marie Therese takes the train to South Orange for classes, where she is excelling. Latin is her best subject (“I could not pronounce it correctly but I do well in exams”). All that she’s learned will return with her to Vietnam when she finishes her degree.

“I will go back and share my knowledge,” she says. And she will share more than just what she learns in theology classes. “In my culture we do not really open up the way you do here. We don’t have a discussion or a dialogue. Now when I go back I can bring the openness.”

Sister Magdalena Chubwa grew up in a remote Tanzanian village where her devout parents grew maize, and where school ended for most children after the equivalent of seventh grade.

“We depend on rain for everything,” says Sister Magdalena, the second-youngest of nine children in her family. “Sometimes it rains too much and we end up losing everything. Sometimes there’s no rain at all.”

Her own education continued, though, when she left home at 14 on a seven-hour train journey to join the Congregation of the Daughters of Mary. She was working toward becoming a teacher in 2008 when her order chose her for additional education, and she came to the College of Saint Elizabeth in Morristown, New Jersey, on a scholarship as a biology major. She then earned a master’s degree in healthcare management and administration there.

“The first six years in America I could not afford to go home, and it was very hard for me to communicate with home,” she says. There was no phone to call, and letters with a U.S. stamp were often intercepted along the way by people who assumed they must contain money.

When she finally did get back home the summer before she finished her master’s degree in 2014, she saw more clearly where her education was leading her: to help Tanzanians get better health care. “I’ve seen a lot of death,” she says. “It’s difficult for people to get medical care. Sometimes when they get there it’s too late and maybe there’s no treatment.”

Before starting her doctoral work, she spent a year in an internship at a medical clinic in Wisconsin, where she learned to drive — a skill that proved essential when her program moved from South Orange to the new Interprofessional Health Sciences campus — and made some friends who traveled with her to Tanzania on her next visit home. “Some of the places I went they didn’t even have a glucometer or a blood pressure machine, some of the most basic equipment,” she says about her visits to medical clinics there.

One way she reacted to what she found was in choosing the topic for her dissertation: how to use telemedicine to improve health care in underserved rural regions. “There’s no internet but they have basic cellphones now, and I want to see if we can use those to help to access medical care in a timely manner,” she says.

She will return again soon, she hopes, to start her research. “She’s a humble and engaging individual, and she really speaks to the notion of mercy,” says Genevieve Zipp, the director of the Center for Interprofessional Education in Health Sciences at the School of Health and Medical Sciences. “She wants to take what she’s learning here and bring it back to her community. She’ll be able to reach out from her order to the health community and make an impact in the world.”

Another way Sister Magdalena reacted to her home country’s needs was more immediate. “I’m learning a lot from school but also from regular life, how Americans do charitable work,” she says. “From what I’ve seen here the people do a lot to help other people. With everything I’ve seen from people in this country, I decided that maybe I can do something.”

So she started Justice and Development for All (JUDEA), a community-based organization in her home parish of Saint Mukasa in Nguruka that brought some equipment for the medical clinic. It also provides 52 elderly people in the village with weekly food deliveries, gave five sewing machines to women who started small businesses making school uniforms, and helped other women start a small soap-making enterprise; and, with $500 for each, is sponsoring 22 children who would not otherwise be able to afford their school fees.

“All this I learned from here,” she says. “All this encouragement I got from the American people.”

Kevin Coyne is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.