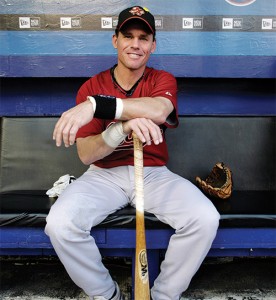

After 20 years with the Houston Astros and a storied career in baseball, former Seton Hall catcher Craig Biggio is inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

On a sunny summer afternoon in Cooperstown, N.Y., the place all baseball players dream of, delivering a speech from a stage on a lush green lawn, Craig Biggio looked out onto a crowd of fans displaying the orange of the Houston Astros, the team he spent his entire career with.

But he also saw a splash of something else. “Pirate blue,” he said later.

“It didn’t go unappreciated.”

Hanging inside the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown was a new bronze plaque that listed the credentials that had earned him his induction and that the fans in orange knew by heart: the 3,060 hits, the seven-time All-Star ranking at both catcher and second base, the “gritty spark plug who ignited Astros offense for 20 major league seasons,” as it described him.

“I was just an East Coast kid from a small hardworking town on Long Island.”

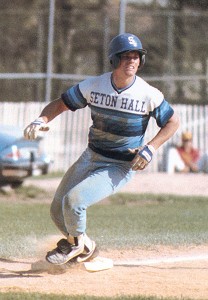

But the fans in blue had known him first. They remembered him as one of the four future big-leaguers (with Mo Vaughn, John Valentin and Kevin Morton) on the Seton Hall baseball team that went 45-10 and won the school’s first BIG EAST championship in 1987. Sitting in the sixth row in Cooperstown, wearing a blue Seton Hall baseball cap, was the coach of that team, Mike Sheppard Sr. ’58/M.A. ’67.

“Maybe by their junior year we know they’re going to be drafted, and after they’re drafted we have an idea of whether they’ll make the majors or not,” said Sheppard, who had 28 winning seasons in his 31 years as coach, won 998 games, and saw 80 of his players drafted and 30 make it to the majors.

Biggio was drafted in the first round by the Astros after his junior year and that stellar season in 1987, and spent just a year in the minors before being called up to Houston. “But I never dreamed for a moment that I was going to have a Hall of Famer,” Sheppard recalled. “How many college coaches can say, ‘I coached a kid that’s in the Hall of Fame?’ ”

Biggio was drafted in the first round by the Astros after his junior year and that stellar season in 1987, and spent just a year in the minors before being called up to Houston. “But I never dreamed for a moment that I was going to have a Hall of Famer,” Sheppard recalled. “How many college coaches can say, ‘I coached a kid that’s in the Hall of Fame?’ ”

Biggio grew up in Kings Park, N.Y., the son of an air traffic controller who, when throwing batting practice, tied him to the backstop with a rope around his waist to keep him from lunging at the ball.

It worked. Biggio had 668 doubles, more than any other right-handed batter in baseball history. He wasn’t big — just under 6 feet — but he was fast, a high-school running back who attracted the attention of Division I football recruiters. As a catcher at Seton Hall, he often beat the batter to first base when racing there to back up the play.

“I was just an East Coast kid from a small hardworking town on Long Island and I went to a blue-collar, hardworking college program,” said Biggio, whose number, 44, was retired by the school in 2012. “It reminded me and continued to reinforce the fact that if you’re going to be successful in life and you’re going to be successful on a baseball field, you’ve got to work, and you’ve got to continue to work.”

It was also at Seton Hall that Biggio met his wife, Patty Egan ’88, a nursing student who worked at the Thursday-night campus pub. “I had no money back then,” he said. “She used to give me free beer and I thought she was cute.” They have two sons, Conor and Cavan, who both played baseball at the University of Notre Dame, and a daughter, Quinn.

Biggio was in Tucson, Arizona, with the Astros’ AAA team while Patty and his other classmates were in South Orange for their senior year. “I thought about it,” he said about going back to finish his degree. “But you know, when you’re playing, when you get to the big leagues, it’s eight months with the playoffs and everything, and there’s no time for that really. You’re committed to your job.”

The 1987 season at Seton Hall was so memorable that it inspired a book, The Hit Men and the Kid Who Batted Ninth, which takes its title from the campus poster that featured Biggio, Vaughn and Marteese Robinson, whose .529 average led the nation, posing as gun-wielding gangsters.

“Craig defines what a Catholic school should be — his hard work, his personality, his caring for people, his humbleness,” said author David Siroty, who was a young assistant sports information director that year, and whose book was published in 2002. “Seton Hall should have retired 44 for every sport. No one should ever wear 44 again, in any sport.”

Only one other Seton Hall athlete has ever been elected to a professional sports hall of fame — Bob Davies, to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1970 — so Biggio’s induction in July was an occasion for great celebration. Coach Sheppard and his extended family stayed in a house Biggio rented for them in Cooperstown and were guests at a private reception the evening after the ceremony. The chairman of the University’s Board of Regents, Patrick Murray ’64/M.B.A. ’72, also made the trip with his own family, all the way from their home in Dallas.

“If you’re going to be successful in life and you’re going to be successful on a baseball field, you’ve got to work, and you’ve got to continue to work.”

“My daughter knew he was from Seton Hall and she knew that I had gone there, so she always followed his career and was a big fan,” Murray said. His family lived in Houston for the first half of Biggio’s career, and he often took his daughter, Suzanne, to games at the Astrodome. “We had talked over the years that if the opportunity came that he was elected to the Hall of Fame, we’d go up there.”

Early on the Sunday morning of the induction, a bus left the Seton Hall campus for the four-hour trip to Cooperstown carrying 50 alumni, many of them wearing blue T-shirts declaring, “From the Hall to the Hall.” Other Seton Hall fans and alumni made the trip on their own. “What’s better than watching one of our own get inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame?” said Patrick Lyons, vice president and director of athletics. “The reason why he had so many people in attendance at Cooperstown was because of the person that he is.”

Early on the Sunday morning of the induction, a bus left the Seton Hall campus for the four-hour trip to Cooperstown carrying 50 alumni, many of them wearing blue T-shirts declaring, “From the Hall to the Hall.” Other Seton Hall fans and alumni made the trip on their own. “What’s better than watching one of our own get inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame?” said Patrick Lyons, vice president and director of athletics. “The reason why he had so many people in attendance at Cooperstown was because of the person that he is.”

This year’s Hall of Fame class — which also included the pitchers Pedro Martinez, Randy Johnson and John Smoltz — drew an exceptionally large crowd of 45,000. “It was Pedro’s and Craig’s audience, without a doubt,” Lyons said.

Biggio was a leadoff batter for much of his career, a reliable hitter who could steal bases once he got on, and in a lineup heavy with pitchers, he was the leadoff man at the ceremony, too. Inductees are allotted 15 minutes for their speeches, and he spent a full two minutes of his remembering Seton Hall.

“My college coach was Mike Sheppard. He was a tough man; he was a Marine. He was a disciplinarian, but he kept you in line. Most of all, he loved his players and he had their backs no matter what,” Biggio said, looking at the spot in the VIP section where Sheppard was sitting. “Coach Shep’s motto was, ‘Never lose your hustle,’ which is something I took to my pro career. I’m very grateful to have played for you, Shep. Thank you.”

The crowd applauded, and a shot of Sheppard appeared on the big screens. Biggio thanked Ed Blankmeyer ’76/M.A.E. ’83, too, Sheppard’s son-in-law, who as a young assistant coach had recruited him out of high school, and then became the longtime baseball coach at St. John’s University.

“He was a tremendous teacher of the game. A man who has dedicated his life to college athletics,” he said. And he thanked the hitting coach, Fred Hopke. “He brought a pro-style approach to the program. He’s the first person that taught me how to work myself through an at-bat.”

And then Biggio detoured briefly away from baseball in a way that may have surprised much of the crowd, but not those wearing blue, thanking the priest who had taught him some important lessons off the field: Monsignor Edwin Sullivan ’42, the baseball team chaplain, who died at the age of 88 in 2009. “He was my roommate on the road at times, but most importantly, he was a friend,” said Biggio, whose parents divorced while he was in college, and who found in the chaplain a wise and sympathetic counsel. “He helped me with my conversion to Catholicism when I was going through a tough time in my life. I miss you very much.”

Biggio told a story from his boyhood, too, about a family on his paper route, the Aldens, who lost their 8-year-old son to leukemia, his inspiration years later to serve as national spokesman for the Sunshine Kids, a charitable organization that helps children with cancer and their families. In the sixth row, Mike Sheppard was seated next to Christopher Alden’s father. “He told me Craig must have been about 13 or something when he told them, ‘If I ever get to be anything, I’m going to do something for kids with cancer,’ ” Sheppard said. His voice wavered, thick with emotion, moved by what his old player showed even then as boy, and by what he had shown since. “And he did.”

Kevin Coyne is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

A Basilian priest who worked in Houston told me how generous Craig Biggio was, especially to Catholic charities. I’m so glad his son is playing on the Blue Jays. I live in Edmonton Alberta Canada, but the Jays have 36 million fans Thank you for the amazing article about Seton Hall. My son & I are huge Irish fans, so I love the fact that his boys attended Notre Dame…James