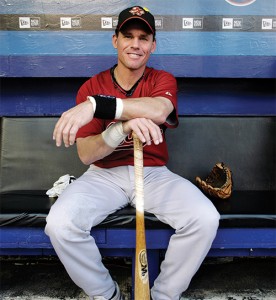

Rather than create a cult of personality around himself, former Pirate baseball player Craig Biggio played hard and respected the game. He ended his pro career in elite historical company.

The painful act of being hit by a pitched baseball is called, in the parlance of the sport, “taking one for the team.” Get a purple bruise on your arm, but reach base, maybe score a run and help your team win. How fitting then that Craig Biggio, the former Seton Hall All-American, would finish his magical 20-year major league baseball career in September 2007 as the modern era’s all-time leader in being hit by pitches. It’s fitting because Biggio — who spent his entire career with the Houston Astros — was, according to those who were associated with him, the ultimate team player.

The painful act of being hit by a pitched baseball is called, in the parlance of the sport, “taking one for the team.” Get a purple bruise on your arm, but reach base, maybe score a run and help your team win. How fitting then that Craig Biggio, the former Seton Hall All-American, would finish his magical 20-year major league baseball career in September 2007 as the modern era’s all-time leader in being hit by pitches. It’s fitting because Biggio — who spent his entire career with the Houston Astros — was, according to those who were associated with him, the ultimate team player.

“If a guy thought he was bigger than the team, he was in trouble with me,” said Mike Sheppard, Biggio’s baseball coach at Seton Hall, now head coach emeritus. “Craig was never that way. Craig was a team player. He was a kid with drive. He had a great hustler’s heart, and a lot of speed.”

Biggio hustled all the way to the end of his career. In a game against the Colorado Rockies on June 28, 2007 in Houston, Biggio hit a single off Aaron Cook, then was thrown out at second base trying to hustle it into a double. No worry. The Minute Maid Park crowd erupted in applause, and Biggio’s Astros teammates mobbed him on the field, for with that hit Biggio had become just the 27th player in the 131-year history of the major leagues to collect 3,000 base hits in a career. He ended his career with 3,060 hits, 20th-most in a career.

Biggio also ended his career with 668 doubles, fifth most in history, and his 146 runs scored in the 1997 season were the most a player had scored in a year for the previous 65 seasons. But to Biggio, his career was about much more than just the numbers. He wasn’t the most gifted member of the 3,000-hit club; in fact, just two of the 27 members had a lower lifetime batting average than his rather modest .281, so the fact that he reached such a lofty plateau was a testimony to his drive, his work ethic and his willingness to play through injuries throughout the years.

“I want to be remembered as a guy who respected the game, who played the game the right way,” said Biggio as he sat in the visitor’s dugout before a September game at Shea Stadium in New York. “I didn’t want to be bigger than the game, and I wanted to be a good role model for the kids.”

If Biggio comes across as an All-American type of guy, well, that’s just the way he is. What you see is what you get.

Seton Hall was crucial to Biggio’s career, he says. “I never would have made it if I had gone pro when I was drafted out of high school,” he said. “I wasn’t mature enough.”

Biggio did much more with his fame as a ball-player, however, than wax eloquent about being a guy who respected the game. In a manner similar to the ethos of the University he attended, Biggio has devoted a great deal of time to helping his fellow man. In 1990, when teammate Larry Andersen was traded away from the Astros, Biggio decided to take Andersen’s place as a fundraising representative for the Sunshine Kids, a Houston-area support organization for children with cancer and their families.

Seventeen years and more than $2.5 million in fundraising later, Biggio is synonymous with the Sunshine Kids. In 1997, he was given the Branch Rickey Award for community service. Last year, Biggio won the Hutch Award, given annually by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, presented to the major league player who “best exemplifies Hutch’s fighting spirit and competitive desire.” As the magazine goes to press, Biggio is among the finalists for major league baseball’s Roberto Clemente Award, its highest honor for community service.

“You need to treat people how you want to be treated yourself,” Biggio said in encapsulating his philosophy of giving. “I enjoy giving back.”

Even in smaller ways, Biggio has always given of himself. Jim Duffy, currently an assistant baseball coach at Seton Hall, was drafted by the Houston organization after his college career ended in 1996. He introduced himself to Biggio in spring training the next year as a fellow former Pirate. The next few days, things started showing up in Duffy’s locker, like extra baseball bats and batting gloves. The clubhouse attendant told Duffy they’d come from Biggio.

“That’s just the kind of guy he is,” Duffy said. “There are hundreds of stories like that.”

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2007 Seton Hall magazine.