Archives are the backbone of our collective memory, a vital thread connecting us to our past, informing our present, and shaping the future. While the perception remains of Archivists locked away in basements amongst dusty shelves and locked cabinets—and trust me, we find ourselves there often!–sometimes the work leads to unexpected projects and places. In November of 2024, Dr. Sarah Ponichtera, Assistant Dean of Special Collections & the Gallery, and Professor Joseph Huddleston of the School of International Relations and Diplomacy, headed to the Sahara Desert to conduct a survey of materials in multiple repositories cared for by the Sahrawi people—a partially recognized state governed by the Polisario Front since 1976. These materials were created by these people, for these people—documenting their history, colonization, and struggle for liberation and independence. Thanks to funding from the Modern Endangered Archives Program, which supports rescue efforts for unique collections all over the world, these materials may now be able to be digitized and shared with the world.

The start of this project began with a simple inquiry from Professor Huddleston in regards to digitization of materials. Huddleston explained the challenges of conducting research in the Sahrawi refugee camps, where he had studied the foreign policy of the Polisario government in exile. Huddleston worked with the Sahrawi people and foreign ministry for many years, and the last time he was there he was granted access to a repository of rare materials but found the information to be in a vulnerable state. The materials are located in a very remote area that is extremely challenging to get to, where there is limited access to the internet and sometimes even electricity. Since the Sahrawi government is not technically part of Algeria, they are not afforded the same resources or services as the rest of the country. Recognizing how important these archives are to not only Huddleston’s research, but to researchers across the world, he sought to digitize the materials himself on his next trip so that he can make this information widely available.

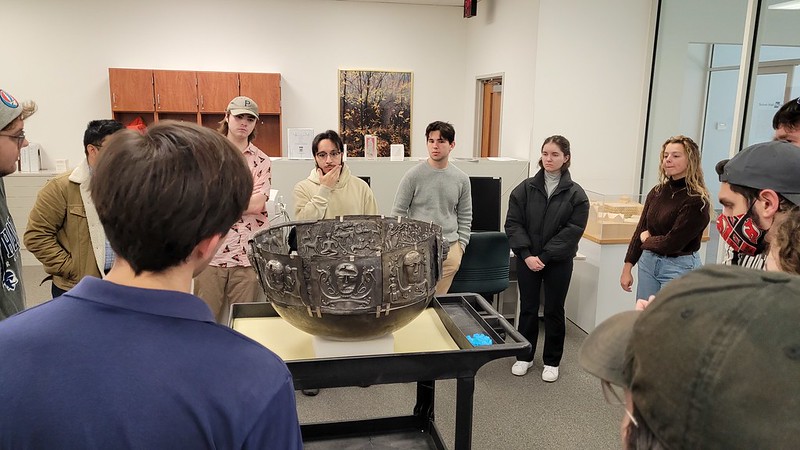

Collaboration between faculty and the archives in a university is common, but for the most part, it is a simple request and exchange of information within the confines of the archives or email. They work within the same spheres, but rarely within the same level of activity. Here there is a unique collaboration between these spheres to conduct a field analysis together—Dr. Ponichtera can bring advice and insight into archival practices of caring for physical materials and process and procedures for digitization, where Huddleston can emphasize how these applications will help to preserve the collective history of these people for generations to come. The goal of this trip was to conduct a survey of materials– what materials are there, how many boxes and containers, getting a better sense of what types of materials there are, what equipment will be needed, and how many people will be needed in order to digitize the collection in a future phase.

Upon arrival, Huddleston and Ponichtera faced a variety of challenges, but also triumphs. First off there were far more collections than previously thought—5 different repositories under 5 different ministries, each with their own levels of care. The archives of the ministry of information, for instance, started as the archive of the local radio and television station that had been documenting the Sahrawi struggle since the 1970s. This poses issues because of so many different formats, different kinds of magnetic tape, and the overall evolution of media that will require specialists to repair and digitize it. There is also the fact that an active conflict is going on in the Western Sahara and sensitive information is sometimes found mixed in with materials meant for public access. And then there is the matter of properly storing the materials themselves. While an NGO from Austria came and built a state-of-the-art archival building that is secure, contains collection storage shelving, and has temperature/humidity control, there is a strong need for folders, boxes, and new types of archival housings for fragile materials such as photographs for which the technology has radically improved within the last decade.

But what Ponichtera and Huddleston want to stress is the tenacity, kindness, and dedication of the Sahrawi people themselves. There is currently a team of 7 professionals who maintain this archive and want to make it accessible to everyone. They have developed their own organizational structure of the materials which fit their specific preservation needs. These materials are not neglected—far from it—it is a just a matter of the lack of resources they currently have which is a sentiment archives from around the world can relate to. What they have been able to preserve in both volume and diversity of materials, is as remarkable as it is inspiring. During their time living within the camp with Sahrawi families, Ponichtera noted how community-minded this community is—anywhere you go you are welcome with open arms, a place to stay, and a warm meal. The creative and independent spirit developed by living in a hostile climate like the Sahara sets the future of this project in good stead. Now that the survey has been conducted, the Sahrawi archivists are creating updated descriptions to enable future researcher access. When this is complete the planning for the full digitization project will begin.

This project is more than just preserving some materials—it is a living repository, a chance for the Sahrawis to tell their OWN stories and experiences, a way for researchers to perhaps change and enrich their understanding of the world. Isn’t that what history is all about?