What is a Bull?

“Bull” refers to the metal seal that authenticates the document, much as we authenticate documents with signatures. The practice dates back to ancient Sumeria, where impressions were made in clay in order to track and authenticate transactions. This practice remained unchanged for 4,000 years. It was adopted by the Romans, who used lead rather than clay. The lead was heated to soften it to create the impression, hence the word “bulla” which derives from the Latin word meaning “to boil.”

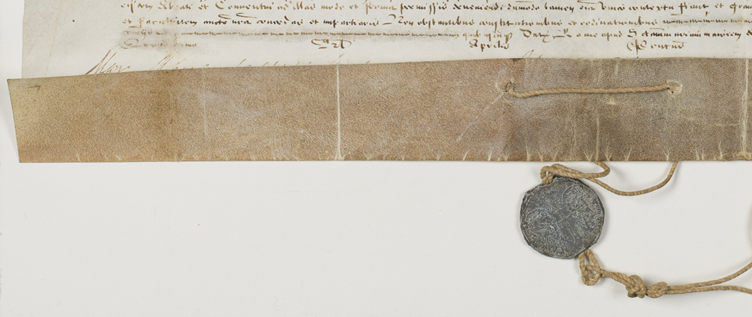

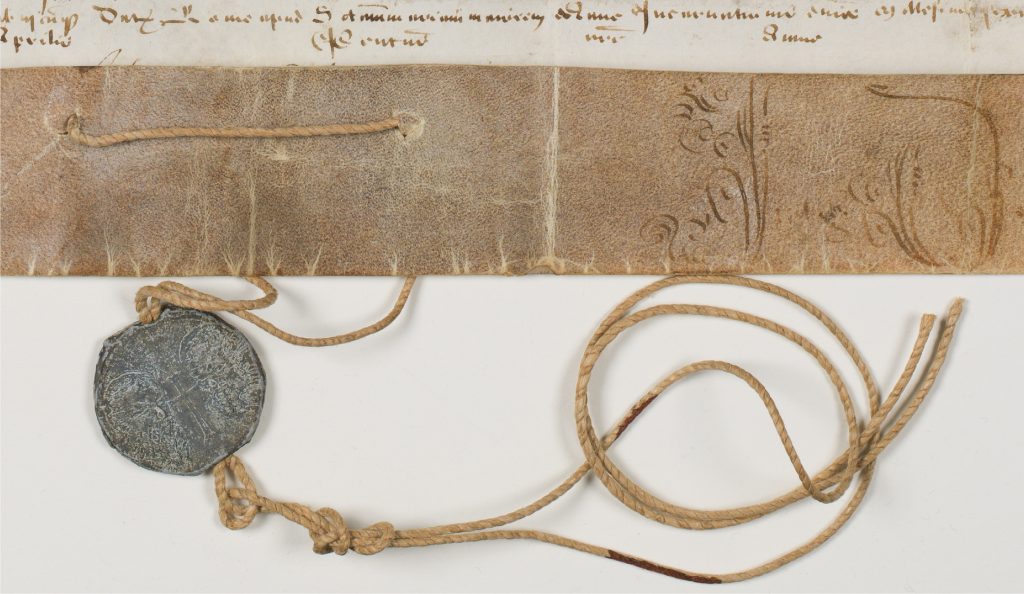

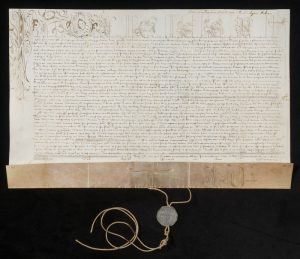

Papal Bulls took on a standardized form, with representations of Saints Peter and Paul pressed into one side of the Bull, and the name of the Pope issuing the decree on the reverse. Below see a close-up of the Bull authenticating this document.

What is this document about?

The matter at hand concerns the alienation of Church property. There was a monastery that had a parcel of land it wished to sell; however, selling Church property required Papal permission. Holding on to ecclesiastical property was a matter of great importance to the medieval Church, since it was the economic foundation of the Church’s activity. The general principle is that a property, once given to the Church is in effect given to God, and no one can legitimately give it to anyone else. The issue here appears to be a relatively minor matter of trading a small and distant field inherited by one of the monks; hence this document delegates the Vicar General (who acted as a kind of business manager) of the diocese of Lodi, the local church authority, to investigate the matter and give the papal permission if he deems it right.

There are many variants of Latin, reflecting the millennia in which the language has been used. This document reflects the use of Latin in the papal court in the early seventeenth century, with a vocabulary reflecting the legalities of land ownership and transfer, and the forms of land measurement and monetary values current in the Italy of that time.

This translation was the work of many hands, but the lion’s share of the credit must go to Professor Emeritus of Religion Peter Ahr, Ph.D., who researched and contextualized the piece as a whole as well as produced the final version of the English translation.

Michael Mascio, Ph.D. ,Lecturer in Classical Studies and Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures made the initial review of the document, and recommended Reverend/Doctor Federico Gallo, Director of the Library at Dottore della Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, who read and transcribed the text. Dr. Mascio then worked together with Fred Booth, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Classical Studies, Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, to produce a first draft of an English translation.

This translation was the work of many hands, but the lion’s share of the credit must go to Professor Emeritus of Religion Peter Ahr, Ph.D., who researched and contextualized the piece as a whole as well as produced the final version of the English translation.

Michael Mascio, Ph.D. ,Lecturer in Classical Studies and Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures made the initial review of the document, and recommended Reverend/Doctor Federico Gallo, Director of the Library at Dottore della Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, who translated the Ecclesiastical Latin version of the text into Contemporary Latin. Dr. Mascio then worked together with Fred Booth, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Classical Studies, Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, to produce a first draft of an English translation from the Contemporary Latin version.

This exhibit is dedicated with many thanks to all the above scholars, without whose work this exhibit would not have been possible.

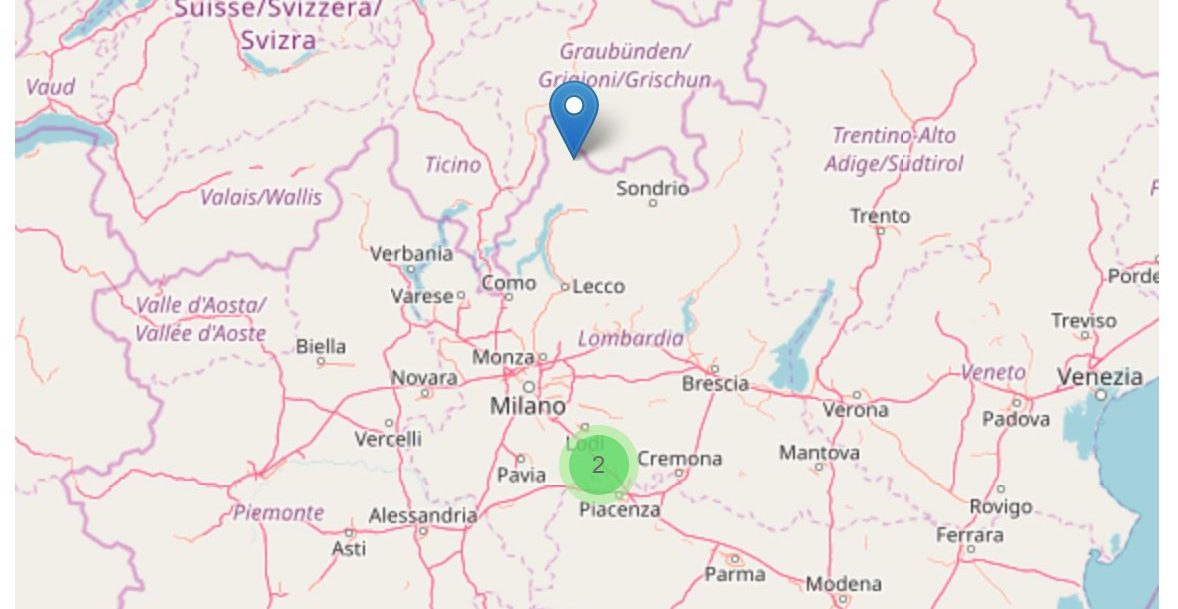

As you can see in this map, the piece of land they wished to sell (represented by the blue dot) was far north of the monastary (represented by the green), on the border with Switzerland (identified here as “della fraggia,” which denotes the region, although not the exact location, of the piece of land in question). Being several days’ distance from the monastary, it likely was not practical for the monks to maintain and manage this property – but because the property was donated to the church (being the inheritance of one of the monks) they needed Papal permission to sell it.

This is the small agricultural town of Ospedaletto Lodigiano, where the monastery petitioning the Pope was located. The town’s population today is about 2,000, about half of whom are immigrants from Brazil and not native Italians; it was almost certainly much smaller in the 17th century.

The abbey of St. Peter in Ospedaletto Lodigiano was the residence of the general of the Hieronymite order, the Hermits of St. Jerome of Lombardy. The order no longer exists, although at one time it had seventeen houses, but this is the abbey church, built in the 16th century to replace the 12th century original. It is now the parish church of Sts. Peter and Paul.

Hieronymites, monks who belonged to the Order of St. Jerome, were inspired by the hermit Saint Jerome to live a life like him, and in line with the ideas of St. Augustine as well. Their name can also be abbreviated to OSH, or Hieronymites, monks who belonged to the Order of St. Jerome, were inspired by the hermit Saint Jerome to live a life like him, and in line with the ideas of St. Augustine as well. Their name can also be abbreviated to OSH, or Ordo Sancti Hieronymi. Founded near Toledo, Spain on October 8th, 1373, they quickly gained importance in both Spain and Portugal, becoming an exempt order in Spain during 1415. Parts of the royal families of both countries were buried in Hieronymite properties, El Escorial in Spain, and Jerónimos Monastery in Portugal. They expanded to Italy, where they would have 17 houses before being suppressed by Pope Clement IX in 1668. This was because of the Hieronymites influence in the Republic of Venice, and the Republic of Venice asking the Pope to suppress the order so they could make more profit. Clement eventually acquiesced, suppressing the order within Italy.The order continued to have influence in Spain and Portugal, becoming involved in bringing Christianity to the New World for both countries. The Order was eventually disbanded in Portugal in 1833, and in Spain in 1835. They also have a sister order of Nuns, which has nunneries dedicated to the order through to the present, and have tried to get the monastic order back since the 1920’s. There is currently one monastery with 11 monks.

The Development of the Hieronymite Order

The Order was established in Toledo, Spain, and was then recognized in 1373 by Pope Gregory the XI. By 1415, they had already been able to establish 25 houses. The order was able to spread rapidly across Spain and Italy because of the popularity of St. Jerome during the 14th century. This was due to people seeing his teachings as consistent and orthodox, during a period of upheaval after the Black Plague. The order was established in Italy in the 14th century, and by the 16th century had worked their way up to 40 houses across Italy at their Peak. It was in 1415 that they were removed from ordinary jurisdiction and made an exempt order. After that they spread to Portugal, and in 1501, the Jeronimos Monastery in Belem was established and built by King Manuel I. That Hieronymite monastery was where the House of Aviz, the Royal family of Portugal was then buried. Spain followed suit in 1559, with the building of El Escorial in Spain, which would be where many Spanish Royals were buried, both from the house of Bourbon and the House of Hapsburg. Both sites are UNESCO world Heritage sites, along with another Hieronymite monastery, Santa Maria de Guadalupe. In 1595, the Spanish and Portuguese orders were combined into one singular order. During the height of their power, they also participated in the evangelization of the New World with Spain and Portugal, spreading their influence to the colonies of both empires.

Excerpted from Studies in Venetian Art and Conservation, 2008. “Saint Jerome and His Order.” Save Venice Inc., Save Venice, savevenice.org/publications/saint-jerome-and-his-order-3/.

“Hieronymites – Encyclopedia Volume – Catholic Encyclopedia.” Catholic Online, Catholic Online, www.catholic.org/encyclopedia/view.php?id=5763.

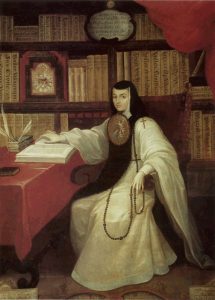

The Habit of the Hieronymite Order

The Hieronymites habit, or religious dress code, is that of a white tunic, with a brown scapular over it, and a brown hood. All of this is worn with a brown mantle. Typical Roman Catholic Monastic orders have a tunic with a scapular, a garment going from the shoulders down and over the from and back, typically reaching the knees. Both the monks of the order, and the nuns wear the same clothing, with their scapular being similar to the scapular of the Carmelite order.

Besse, Jean. “Hieronymites.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.6 Sept. 2018 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07345a.htm>.

Juana Inés de la Cruz

Born in 1651 (or 1648, birth records differentiate) in San Miguel Nepantla, Mexico. She was a highly intelligent child and consider a prodigy, and showed from a young age an attraction to scholarship and a preference not to marry. By 1667 she chose to be a nun, and briefly stayed with a Carmelite order before settling with the order of Hieronymite nuns in Mexico City. Her writing covered everything from secular love poetry to scholarly works, to plays of any time of genre. She is credited as the first published feminist of the new world, her writings supporting women’s rights and defending her own right to study a wide variety of topics. She retired from her writing career in 1694, selling her library to benefit the poor. She passed while helping her fellow nuns through plague in 1695.

From Wikimedia Commons.

Merrim, Stephanie. “Sor Juana Inés De La Cruz.”Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 10 Apr. 2018, www.britannica.com/biography/Sor-Juana-Ines-de-la-Cruz.

“Sor Juana Inés De La Cruz.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 26 July 2016, www.biography.com/people/sor-juana-in%C3%A9s-de-la-cruz-38178.

Who issued this Bull?

Pope Paul II (Pietro Barbo)

Born: 23 February 1417, Died: 26 July 1471. Pontiff, Bishop of Rome: 30 August 1464 to his death on 26 July 1471.

The author of the bull itself is the well-known Pope Paul V Borghese (1605-1621) who wrote it according to the decree set forth by Pope Paul II.

Pope Paul V was educated as a lawyer, a renowned expert on canon law, and jealous of Church authority and property. He is remembered as the pope who clashed with Galileo, forbidding him to publicly support the Copernican theory of the universe, and as a great patron of the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini. He often mediated political conflicts and sometimes was at the center of disputes, such as one with Venice in 1606 that almost escalated into a war. Pope Paul V also financed the completion of St. Peter’s Basilica, the Vatican and anyone who has seen the façade of St. Peter’s has seen Paul V’s name prominently carved over the central door of the basilica, perhaps one of the most successful billboards in history.

Bibliography

“Paul V,” Encyclopedia.com (Encyclopedia of World Biography), https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/philosophy-and-religion/roman-catholic-popes-and-antipopes/paul-v (August 24, 2018).

Who issued the Bull?

Pope Paul II (Pietro Barbo)

Born: 23 February 1417, Died: 26 July 1471. Pontiff, Bishop of Rome: 30 August 1464 to his death on 26 July 1471.

The document begins with a decree of Pope Paul II Barbo (1464-1471) on general principles governing alienation of church property. It includes the command (followed here) that any later document delegating any authority over such alienation include the full text of his decree.

Pope Paul II, the nephew of his predecessor Eugene IV, is remembered for his ostentation, his fondness for gemstones, and for his construction of what is now the Palazzo Venezia in Rome as his residence. Although he was an opponent of humanist learning, he permitted the first printing presses in Rome. He was also a strong opponent of bribery and trafficking in religious offices. Overall, the Papacy of Paul II was marked by few accomplishments and an autocratic rule over the College of Cardinals. Because of this and his devotion to games and festivities, scholars rank him as one of the worst of the Renaissance popes.

Bibliography

“Paul II,” Encyclopedia.com (Encyclopedia of World Biography), https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/philosophy-and-religion/roman-catholic-popes-and-antipopes/paul-ii (August 25, 2018).

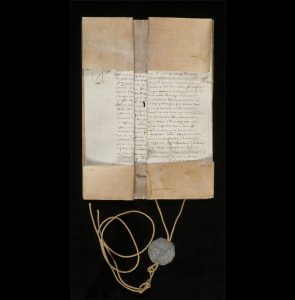

In order to make the Bull available for research and translation, condition issues needed to be addressed. The document was brought to paper conservators at the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts in Philadelphia for assessment and treatment.

The most significant issue was that the parchment had been tightly folded for many years, so that it could not be unfolded without risking damage. This made it impossible to view the full text of the document and learn about its history.

Conservators used a process called humidification, in which moisture is carefully introduced to the parchment in order to relax it and increase its flexibility. Using this technique, the parchment could be flattened without damage.

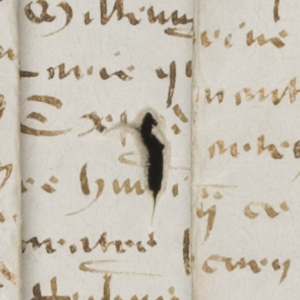

Another issue conservators addressed was a small hole in the center of the parchment. This may be the result of previous damage or an inherent defect in the animal skin used to make the parchment.

In order to mend the hole, conservators used mulberry paper, a type of Japanese paper with long, strong fibers and neutral PH. The paper was toned to match the document and applied with special archival adhesives. Repairs like this are designed to be reversible with the proper techniques, so that the document can be restored to its original state if necessary.

Once conservation was completed, the unfolded document revealed some additional clues about its history. Careful examination by Dr. Peter Ahr enabled him to identify the type of ink used, distinguish the contributions of several different people who helped to create the document, and discover additional signatures hidden in the bottom fold of the document.

From Wikimedia Commons.

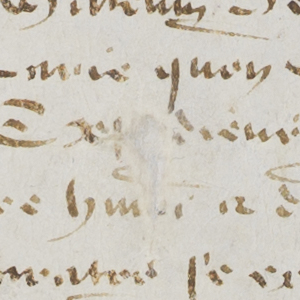

The Ink

The text was written in iron gall ink, made from the gall, or fruit, of the oak tree. It would have originally been black, but has faded to brown over time. The scribe did not dip his quill frequently enough while writing, so the ink fades as the line continues to the right. This can be seen most clearly at the end of a line, where the faded ink contrasts with the deeper ink.

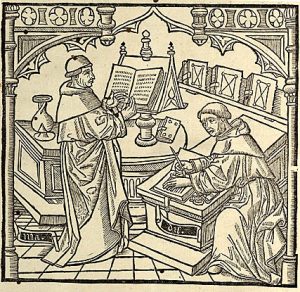

Scribes in the Early Medieval Period

This illustration depicts monastic scribes at work in the early medieval period. Though the time period is much earlier than the 17th century papal scribes who created this Papal Bull, the method they are using was the same. One scribe stands at a lectern reading out the text, while another writes it down. This would have been tedious work, and the tiredness of the scribe is reflected in several aspects of the document, including the faded ink and the number of corrections made to the text.

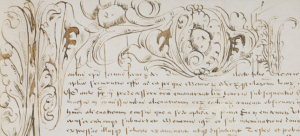

Text Avoids Decoration

The way that the text of the document is fitted around the calligraphy shows that the calligraphy was probably done first by a dedicated illuminator. The text itself would have been added later by a professional scribe in the papal chancery.

Concealed Signatures

Due to the way the cord holding the bulla is threaded through the document, the very bottom fold cannot be opened. As a result, three additional signatures are concealed by the fold and cannot be accessed and read. These were likely other officials whose approval was needed in this matter, but we cannot know for certain without cutting the cord that holds the bulla.