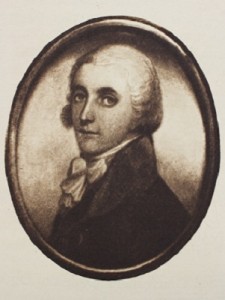

This was the refrain heard from the floor to rafters of Convention Hall, Philadelphia during the summer of 1940 and echoed through that autumn when the Republican Party nominated corporate lawyer and long time political booster Wendell Lewis Willkie of Indiana as their standard bearer for the upcoming presidential election of that year. Willkie (1892-1944), who never held public office was an outspoken internationalist who later became an informal ambassador-at-large for important causes including global welfare programs and civil rights most notably as outlined in his seminal work: One World(located in the Walsh Library Main Collection, Call Number: D811.5 .W495) which heralded the need for a “world government” to aid society at-large which would later come to fruition in part through the establishment of the United Nations a few years after its publication in 1944.

Willkie focused his run for the White House on three primary themes which included the lack of military readiness in case of war, streamlining the “New Deal” programs of incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the never before attempted third term candidacy of a sitting president. In the end, Willkie lost the race, but registered 22.3 million votes nationwide (more than any previous Republican candidate at this point) and won 82 electoral votes (plurality in ten states) total.

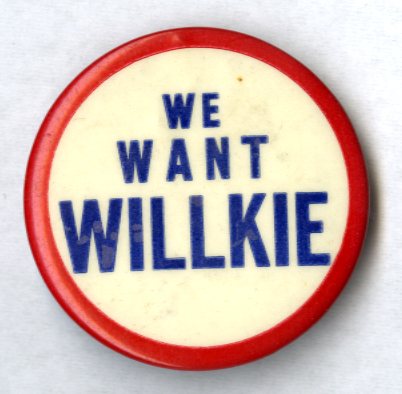

Although defeated, the successful legacy of Wendell Willkie is celebrated in the Seton Hall Archives & Special Collections Center through the availability of varied resources regarding the candidacy of this icon in American political history. Included are a unique set of scrapbooks donated by Maplewood resident, Mr. Jack Chance who followed this election closely and documented the 1940 race through a collected series of local and national press clippings. Famed funeral director Mr. Gerald Spatola of Newark served as a delegate from New Jersey to the 1940 G.O.P. convention and in turn left a convention book as a reminder of civic activity on a national stage. Additionally, our political science department has collected various campaign buttons over the years and Wendell Willkie figures prominent among them and serves a tangible reminder of his candidacy seven decades ago.  A further point of connections was made more valid and vivid during that fall of 1940 when Willkie in the midst of a national spotlight was invited to visit campus by former College President, James Kelley, but in an October 15th letter from the candidate to the chief executive of Seton Hall he wrote regrets for being unable to make his way to South Orange, but praised the work of the school in a larger context inside the following passage…

A further point of connections was made more valid and vivid during that fall of 1940 when Willkie in the midst of a national spotlight was invited to visit campus by former College President, James Kelley, but in an October 15th letter from the candidate to the chief executive of Seton Hall he wrote regrets for being unable to make his way to South Orange, but praised the work of the school in a larger context inside the following passage…

“As a mid-Westerner, I am of course not intimately familiar with Seton Hall, but I am fully aware of the splendid educational work done by the Catholic clergy at many institutions throughout the land…the College was founded by and named for collateral ancestors of President Roosevelt. I was extremely interested to hear of the pioneer work of Bishop Bayley and Mother Seton in New Jersey. The State and the Nation are profiting greatly from the untiring efforts of these inspired people and others like them…It is hope that the college may long be able to continue its educational and character-building endeavors, that it may never have to encounter the hatreds and oppressions which have perverted or destroyed so many similar institutions in other lands.”

Just like 1940, if you want Willkie and learn more about his life and times please feel free to make an appointment with us to explore in further depth and detail. We can be reached by e-mail: Archives@shu.edu, or by phone: (973) 275-2378. Thank you in advance for your interest.