The Korean Migration

Bias and Prejudice, War and Welcome

“A few Koreans came to the United States in the late 1800s, but it wasn’t until 1903 that Korean immigration began in earnest.”1 By 1905, over 7,000 migrants had left Korea, almost all settling in the sugar plantations in Hawaii. With Japan’s occupation of Korea in 1910, and the implementation of more restrictive United States immigration laws, very few Koreans came to America in the first half of the 20th century. Apparently, hardly any came to New Jersey. In its 1920 report, the United States Census Bureau reported that there was only one Korean living in New Jersey. However, this has been contradicted by Father Jungsoo Kim, who informed me that he was aware of other Koreans in New Jersey at that time. I will go with Father Jungsoo’s information!

The Immigration Act of 1924 established the National Origins Quota System. It severely curtailed immigration from Eastern and Southern European countries, thereby excluding most Catholics and Jews. Building on the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and other biased anti-Asian legislation, it completely abolished immigration from 39 Asian Countries. Although no specific census category existed for Koreans until the 1970 census, the 1930 and 1940 census reported twelve Koreans living in New Jersey.

In 1960, various sources estimated that there were about 11,000 Korean immigrants in the United States. Most of these were “war brides,” children of American soldiers of the Korean War, and others admitted as refugees. On the heels of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, immigration policy changed drastically. With the passage of the Immigration Reform Act of 1965, Koreans began to immigrate to the United States in significant numbers. In the years 1965-1970, the United States welcomed 27,757 legal Korean immigrants.

The numbers rose dramatically between 1971 and 1980, with 267,638 newcomers from the Korean Peninsula. The United States received 333,746 Korean immigrants between 1981 and 1990. This wave of Korean immigration peaked in 1987, at 35,849 in that year alone. Thereafter, Korean immigration to the United States declined somewhat. In all, 164,166 Koreans made the United States their new home in the 1991-2000 period. By 2008, there were over one million Korean-born residents in the United States.2 In 2017, 1.7 million Americans identified as Korean.3

The numbers rose dramatically between 1971 and 1980, with 267,638 newcomers from the Korean Peninsula. The United States received 333,746 Korean immigrants between 1981 and 1990. This wave of Korean immigration peaked in 1987, at 35,849 in that year alone. Thereafter, Korean immigration to the United States declined somewhat. In all, 164,166 Koreans made the United States their new home in the 1991-2000 period. By 2008, there were over one million Korean-born residents in the United States.2 In 2017, 1.7 million Americans identified as Korean.3

Today, much of the recent Korean immigration is different in character from the earlier immigration. Many come to the U.S. already educated, with significant resources and the possibility of one day returning to Korea.4 The Korean population in New Jersey went from negligible in 1965 to almost 40,000 twenty-five years later and more than doubled again by 2010.

Korean Population in New Jersey

| 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2017* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1** | 12 | 12 | n/a | n/a | 2,349 | 13,173 | 38,540 | 65,349 | 93,697 | 114,899 |

Decennial dates are Official United States Census

*United States Census Bureau Estimate

**Father Jungsoo Kim disputes this statistic.

Locally, as the Korean immigration continued into the late 20th and early 21st centuries, most Koreans settled in Bergen County, particularly in southern Bergen County, and others scattered throughout northern New Jersey. Only Los Angeles and Orange Counties in California, and Queens County in New York, have a larger Korean population than Bergen County. However, in the 2010 census, Bergen County had the highest Korean percentage of the population (6.43 percent) than any other county in the United States.5

These United States Census Bureau figures are for all Korean-heritage residents. They are not the number of Catholic residents. The Korean American Catholic population also includes first-, second-, and now third-generation Catholics. These statistics illustrate the concentration of Koreans in Bergen County. They also show that the great majority of Korean-heritage New Jersey residents, more 60 percent, live in the four counties of the archdiocese of Newark.

Korean – 2010 Census by County

| Total NJ | Bergen | Essex | Hudson | Union | RCAN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 93,679 | 56,773 | 2,447 | 4,791 | 1,259 | 65,270 | |

| 2017* | 114,899 | 59,018 | 3,133 | 5,755 | 1,887 | 69,793 |

(RCAN – Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark)

Decennial dates are Official United States Census

*United States Census Bureau Estimate

Pastoral care for the Korean immigrants followed traditional patterns but with specific differences adapted to the needs of the Korean Catholics. Unlike the European immigration experience in the early 1900s, native clergy did not accompany the Korean immigrants in the late 20th century. The Korean bishops did not initiate a pastoral plan for the care of their people in the diaspora because of their own growing pains back home. Many dioceses in Korea focused on nurturing Korean vocations in the hopes of replacing foreign missioners to meet the needs of the growing Catholic population in Korea.

Saint Andrew Kim, Maplewood

The beginnings of these Korean immigrant communities in the 1970s and 1980s possessed several common traits. They first gathered into small groups, then formed lay leaders, and finally invited priestly leadership. This lay initiative among Koreans in the United States mirrors the origins of the Korean Catholic community in the 18th century. This community was initially based on exclusively lay evangelization.

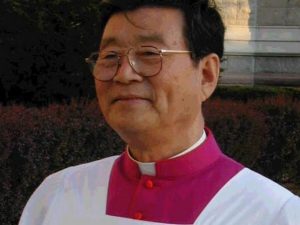

In New Jersey, the pattern of the pastoral care of the Korean community is largely the result of the long ministry of Monsignor Augustine Park. Ordained in 1961, Father Park had studied at Seoul Catholic University, the Mission Étranger in Paris, and the Collegio San Pietro in Rome. Under his leadership, the Korean immigrant community became a national parish within the archdiocesan structure. They rapidly spread to other parts of the archdiocese forming a variety of parochial configurations

The 1970 census records 2,349 Koreans in New Jersey, perhaps 300 to 400 of them Catholic. In the early 1970s, the newly arrived Korean Catholics formed a community center under the direction of Father Augustine Park. At this time, their rather small number was scattered. Father Park had come to the United States for further academic studies. Seeing the pastoral need, he quickly began to minister to Korean Catholics, who had no priestly leadership.

Father Park celebrated the first Mass in Korean in Our Lady of Victories Parish in Jersey City on December 3, 1972. This milestone is considered the beginning of Saint Andrew Kim Korean Catholic Church. The Korean community also gathered for Mass in Orange, Teaneck, Fort Lee, and other cities on different Sundays. To have a place suitable for liturgy, in 1974 the congregation moved and began to celebrate Mass in Saint Perter Claver Church, an African American parish, in Montclair. A committee raised funds for a place of their own and, in 1980, the congregation purchased a former Christian Science Church in Orange. When it moved there, it was officially named the Saint Andrew Kim Korean Catholic Mission of New Jersey. The community continued to expand, and soon Mass was celebrated in Eatontown and in Madonna Church in Fort Lee.

The community was growing and needed more facilities. Saint Venantius Parish in Orange, originally a German-language parish, had few remaining parishioners. In 1986, Father Park was incardinated into the Archdiocese of Newark. The same year, the archdiocese merged Saint Andrew Kim with Saint Venantius Parish, and appointed Father Park as pastor. Father Park was installed as Pastor of Saint Venantius – Saint Andrew Kim Parish on March 29, 1987. The Korean community of Saint Andrew Kim now shared facilities with the English-speaking congregation of Saint Venantius Parish.6However, the former Saint Venantius Parish complex in Orange was quite old and rather small. In 2005, the archdiocese relocated Saint Andrew Kim Korean Parish to the newer and more spacious site of the former Immaculate Heart of Mary Parish in Maplewood.

In the early years, Saint Andrew Kim Community averaged 350 parishioners at Sunday Mass.7 Giving the Korean community the status of a “Personal” or “National” parish was different from the pattern of addressing the pastoral needs of the Korean community in California. In San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Orange, the norm was to encourage Korean community centers that often were separate from parish structures.

Through the years, the pastoral response in the archdiocese of Newark was diverse. Even with a great deal of work, Korean is a difficult language for Euro-American priests to master. There clearly was a need for Korean priests. Most Korean diaspora communities were not able to receive pastoral care by a native Korean-speaking priest until Korean vocations flourished and reached unprecedented heights in the 1990s and 2000s. Korean bishops, who now had more priests, were willing to allow some of their priests to minister in the United States for three to four years before returning to their home diocese.

Korean women religious also went overseas on assignments of several years to address some of the immigrants’ spiritual concerns.8 Today, several congregations of Korean Sisters minister in the archdiocese of Newark. They are the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of Mirenae, the Sisters Apostles of the Descent of the Holy Spirit, formerly known as the sisters of Peace Pentecost, the Sisters of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, the Congregation of Kkottongnae Sisters of Jesus, and the Caritas Sisters of Miyazaki.

At the same time, with great foresight, Father Park recruited Korean seminarians from the immigrant community and from Korea. They enrolled in Immaculate Conception Seminary and were ordained for the archdiocese of Newark. These young men had the opportunity to sharpen their English language skills and, during their seminary years, to grow in their understanding of the culture of the Church in America, the culture in which all Korean America Catholics now participated.

Upon ordination, these priests ministered to the growing Korean community and in non-Korean parishes as well. Where and when needed, the practice of bringing Korean priests for three- to four-year terms continued.

The Korean Communities of Bergen County

While Saint Andrew Kim Parish initially was the only official Korean parish in the archdiocese of Newark, it soon became clear that the center of the New Jersey Korean community was developing in Bergen County. The growth of the Korean presence in Bergen County, second only to Southern California, was manifest in several ways, each following a pattern of immigrant pastoral care. As Father Park became aware of the growing Korean population, he consulted with some of the younger Korean priests and arranged for the celebration of Mass in Korean for growing communities in Fort Lee, Teaneck, Palisades Park, Saddle Brook, and Demarest. The Teaneck community later moved to Fort Lee and then to Saddle Brook.

St. Joseph’s Korean Catholic Community in Demarest was started in 1988 by Monsignor Park as a mission of Saint Andrew Kim Parish in Orange. Monsignor Park invited priests from Incheon Diocese to administer the mission in 1990. The mission rented space from Saint Joseph Parish. It was later erected as a canonical National parish, Saint Joseph Korean Catholic Church, in 1998, and continued to be served by priests from the Incheon Diocese until 2006. That year Father Jungsoo Kim became administrator. In 2008, the parish was merged with Saint Joseph’s Parish through the New Energies Project.

The merged parish enabled second and third generation families to get involved in the English masses, which quickly grew in attendance, fueled by the significant growth of young Korean American families.

The Teaneck community that had moved to Fort Lee and then to Saddle Brook had grown. In 1998, the archdiocese established the parish of Korean Martyrs in Saddle Brook as a Korean National Parish. There were now three Korean “National” or “Personal” parishes in the archdiocese of Newark.

As did many immigrants of the late 20th and early 21st century, Koreans also entered existing parishes. In some cases, they rather quickly became almost half of the parish. This took place in Madonna Parish in Fort Lee and in Saint Michael’s Parish in Palisades Park. Saint Michael’s recently added a Spanish Mass to its schedule of English and Korean Masses.

Here again, in the parishes where they grew in numbers, the Korean experience is a bit different from other contemporary immigrant groups. Most likely because of significant language and cultural differences, the Korean community is more autonomous than immigrant groups in other parishes.

The four Bergen County parishes draw some of their parishioners from their own neighborhood and many others from a distance as people choose among them in the same way all other Catholics choose their parish today. Saint Andrew Kim has fewer parishioners in its immediate neighborhood and draws most parishioners from a distance.

The structure of ministry within the Korean community thereby encompasses both national parishes and existing territorial parishes that, over the years, have developed into parishes with a substantial autonomous Korean community.

Reflections

As we address the pastoral needs of each new immigrant group, it is necessary to note that the immigration of the last fifty years is very different from that of a century ago. A century ago, although the migrants came from different nations of Europe with different Catholic cultures, they possessed similarities to one another. All were Caucasian. All spoke languages of the various European linguistic families. All shared various aspects of a common European heritage. Our recent and current immigrants come from every continent, from Latin America, Asia, and Africa. They possess diverse racial and cultural backgrounds. While structures may appear similar to the past, the pastoral strategies of the past will not always be effective. “Assimilation” will not take place in the same way or at the same pace as it did with European immigrants a century or more ago.

If there was ever a linear process by which immigrants assimilated to American culture, it no longer exists. If in the past immigrants (or more likely their children) first became ethnics and later plain Americans, today the picture is more complex… (T)here is no longer just one “America” that newcomers enter not only one “American identity” that they may adopt. Newcomers encounter a pluralistic social context rich with types and categories to which they may be assigned.9

It is difficult to state the exact number of Korean Catholics, or any group of Catholics for that matter. In 1993, sources estimated that 13.6 percent of Koreans in the United States were Catholics.10 However, a Pew Survey in 2014 estimated the number at 10.2 percent.11 Some estimate that the Catholic proportion of Korean immigrants is higher than the Catholic population in Korea, so it may actually be about 15 percent or more. When we compare percentages of the United States census numbers of all Koreans and the parish reports, we get a reasonable idea of the number of Korean Catholics.

Why do these discrepancies exist? The Columban Fathers, who minister to the Korean population in southern California, note that many Koreans who came to the United States as Catholics joined Protestant churches due to the lack of Korean language services in Catholic churches.12 This was not unusual. Throughout American history, many immigrant Catholics that did not receive adequate pastoral services in their native language left the Church. It is no different for the Korean community in New Jersey. Korean Protestant churches are ubiquitous. There are dozens of Korean Protestant communities in Bergen County as many American Protestant churches, whose numbers are dwindling, allow their Korean counterparts to use their facilities.

Even more troubling, the 2014 Pew Survey reports that more than one-quarter of Korean Americans brought up as Catholic became Protestant or Evangelical, and another quarter indicated that they had no religion, only 47 percent remaining Catholic.13 This may reflect strengthening secular trends in both American and Korean societies. Clearly, this is a challenge for the Korean American community. However, there is an outlier among the statistics. R. Stephen Warner, Korean Americans and Their Religions: Pilgrims and Missionaries from a Different Shore claims that 70 percent of Korean Americans are Christians.14

Mass Attendance Reports and Estimates of Number of Parishioners15

| Parish | Mass attendance | Parishioners | Korean Parishioners |

|---|---|---|---|

| St. Andrew Kim | 404 | 1,198 | 1,170 |

| St. Joseph | 1,007 | 2,710 | 1,626 (.6 Korean) |

| St. Michael | 944 | 2,082 | 1,665 (.8 Korean) |

| Korean Martyrs | 807 | 1,879 | 1,850 |

| Madonna | 1,464 | 3,874 | 1,937 (.5 Korean) |

| 8,248

|

Korean Population in select cities – 2010 census

| Town | Korean Population | Korean Percentage of population |

|---|---|---|

| Palisades Park | 10,115 | 51.5 |

| Fort Lee | 8,318 | 23.5 |

| Ridgefield | 2,835 | 25.7 |

| Leonia | 2,369 | 26.5 |

| Edgewater | 2,258 | 19.6 |

| Cliffside Park | 1,797 | 7.6 |

| Closter | 1,771 | 16.3 |

| Cresskill | 1,522 | 17.8 |

| River Edge | 1,264 | 11.1 |

| Englewood Cliffs | 1,072 | 20.3 |

| Northvale | 757 | 16.3 |

The pastors of the Korean parishes estimate 8,248 parishioners, given the approximation of percentages noted. If the various national surveys approximate the number of Korean Americans who are Catholic at about 13 percent, we come to a similar number. Thirteen percent of the total 65,270 Koreans the census records in New Jersey is 8,485. Of course, Korean American Catholics who attend non-Korean parishes and undocumented immigrants must be considered as well.

Estimates of the number of undocumented Korean migrants in the United States extend from 180,000 to 230,000, which is ten to twelve percent of the approximately 1.8 million Korean Americans. An estimated 10,000 Koreans are eligible for DACA status.16

Ten percent of the estimated more than 8,000 Korean Catholics in the archdiocese of Newark would add almost 1,000 undocumented Korean Catholics to the total.

«V. The Second Wave and The Great Hispanic Migration and Immigration Part Two« : »VII. Filipino Immigration»

Footnotes

- Sheila Smith Noonan. Korean Immigration. Broomall PA, 2004, 48.

- Korean Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. August 24, 2010. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/korean-immigrants-united-states-0

- This includes many born in the United States of Korean parents.

- Simon C. Kim. Memory and Honor. Collegeville 2013: 44.

- The Daily Viz. Mapping the United States Korean Population. http://thedailyviz.com/2018/01/23/mapping-the-united-states-korean-population/

- Summary of Parish History in commemorative booklet and program entitled 100 – Centennial Celebration 1887-1987 Saint Venantius – Saint Andrew Kim Church Orange New Jersey.

- Archdiocese of Newark, Office of Research and Planning, Mass Attendance ’83 to ’17.h

- Simon C. Kim. Memory and Honor. 65-70 passim

- R. Stephen Warner, “Introduction: Immigration and Religious Communities in the United States,” in Gathering in Diaspora: Religious Communities and the New Immigration, ed. R. Stephen Warner and Judith G. Wittmer. Philadelphia, 1998, 25.

- Susan B. Gail and Kwang Chung Kim, eds. Statistical Record of Asian Americans. Detroit, Gale Research, 1993, 848.

- Chaeyoon Lim. “Korean American Catholics” in the “Changing American Religious Landscape: A Statistical Portrait,” in Simon C. Kim and Francis Daeshin Kim, Embracing our Inheritance, Eugene, Oregon: 2016, 49.

- Angelyn Dries. “Korean Catholics in the United States” in U. S. Catholic Historian, v. 18, n. 1, Asian-American Catholics (Winter, 2000), 102-103.

- Lim, 55.

- Cited in Sheila Smith Noonan. Korean Immigration. Broomall PA, 2004, 59.

- Archdiocese of Newark, Office of Research and Planning.

- http://www.browndailyherald.com/2018/02/02/20-kim-18-support-undocumented-asian-immigrants/