1920 – 1965

Introduction

After the end of World War I, President Harding promised a return to “normalcy.” In the United States as a whole and in the Church in Newark, things did not return to the pre-war world. Congress passed anti-immigration laws and the constant flow of new Catholic immigrants disappeared. Many Catholics thought that the era of the immigrant church was over; and, it was, for a while. Catholic pastoral activity shifted from helping newcomers adapt and preserve the faith to providing the necessary structures for supporting an active Catholic life for an increasingly native-born population.

The general population was changing as well. The “Great Migration” of African Americans from the south to industrialized parts of the nation where there were jobs changed the composition of the population in northern New Jersey. The post-World War I era saw the spectacular growth of suburbs, better wages for workers, the advent of the automobile, and the mobility it engendered.

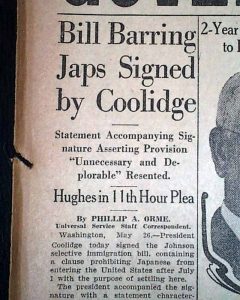

Legal Public Prejudice and Bigotry – Anti-Asian Laws

The “Closing of the Door”

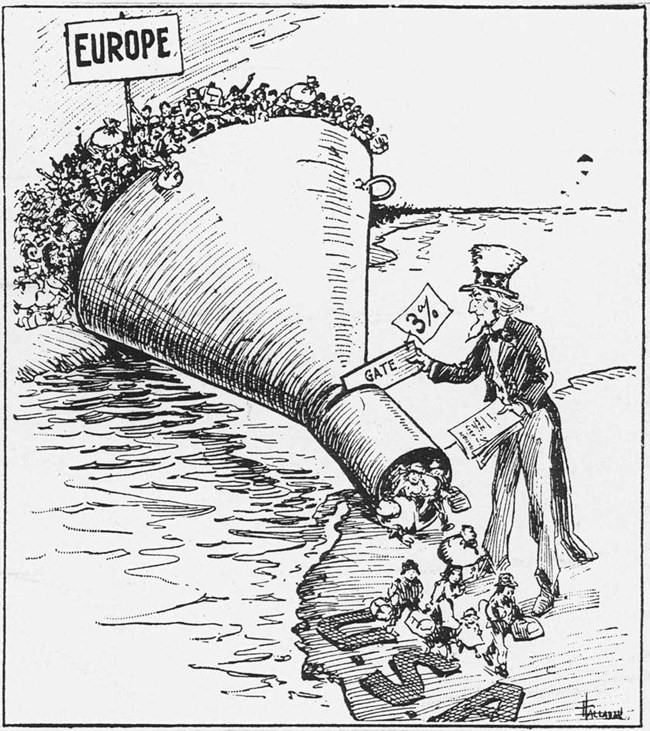

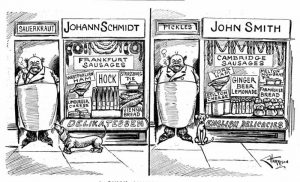

The great increase in immigration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries produced an anti-immigration and anti-foreigner backlash in the United States. A desire to keep the United States a majority white, Anglo-Saxon or at least northern European, Protestant country brought about extremely bigoted, racist, anti-Catholic, and anti-Jewish legislation. Anti-Asian bigotry needed no disguise with the passage of laws with names such as the “Chinese Exclusion Act” of 1882 that prohibited most immigration from Asia. The Chinese were welcome as laborers that built the transcontinental railroad but were expected to return to China upon the completion of that task. Anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish prejudice masqueraded under early 20th century laws that restricted immigrants to artificial national quotas that resulted in as few Catholic, Jewish, central and southern European immigrants as possible.

Congress codified Anti-Asian legislation in the Immigration Act of 1917 that prohibited immigration from a “banned zone” that included most of Asia but not the Philippines or Japan. However, under the so-called “Gentlemen’s Agreement” of 1907, the United States did not impose restrictions on Japanese immigration, and, in turn, Japan would not allow further emigration to the United States. This included Korea, since it was occupied by Japan from 1910 to 1945. In addition to the Chinese, Indians, Indonesians, and other banned nationalities, the act added insult to injury by linking all Asians to other banned “undesirables.” These included alcoholics, anarchists, contract laborers, criminals, convicts, epileptics, feebleminded persons, idiots, illiterates, imbeciles, insane persons, paupers, persons afflicted with contagious disease, persons with physical or mental defects, persons with constitutional psychopathic inferiority, political radicals, polygamists, prostitutes, and vagrants.

Despite these restrictions, there was a trickle of immigration from many “banned” areas of the globe. Political necessity eventually led to the mitigation of some anti-Asian immigration regulations over time. The United States lightened restrictions on Chinese immigration only in 1943, after the United States and China became allies in the war against Japan. After the Korean War, legislation made exceptions for “war brides” of American soldiers.

The Door Slams Closed

The gradual development of mid-20th century American Catholicism partly was a result of a decrease in immigration following these restrictive immigration laws. The 1921 Emergency Quota Act limited immigration from any European country to three percent of the number of people from that country residing in the United States in 1910. The 1924 Johnson-Reed Act further reduced the number to two percent of a specific nationality’s population in the United States in 1890.

In addition to the restrictive laws, the economic crisis of the 1930s, the “Great Depression,” followed by the massive dislocations of World War II (1939-1945), drastically reduced the number of immigrants. Despite these restrictions, under the quotas, limited numbers of Europeans, chiefly Spanish, Portuguese, Italians, and Polish, immigrated to the United States before and after World War II.

Before these 20th century restrictions and international crises, hundreds of thousands of Catholics annually entered the United States. They sparked an unprecedented and rapid growth in Church membership. The American Catholic Church met this challenge with a proliferation of institutions, parishes, parochial schools, seminaries, convents, and colleges, and the development of religious communities to serve them. These waves of immigrants and their children filled the seminaries and convents. This institutional growth would be even greater during the “pause” in immigration.

Major Institutional Development during the “Pause”

With the immigration restrictions in place, the Church was given time to consolidate its gains and improve its parochial and educational structures without the challenge of providing for sudden waves of new arrivals every year. Coincidentally, this was a period of unprecedented growth in vocations to the priesthood and religious life, providing personnel to care for the Catholic populations. As generations passed, Catholics assimilated into the political, social, and economic structure of the nation, some achieving great success and affluence.

From 1910 to 1920, the decade immediately before the enactment of quota restrictions, Bishop O’Connor created 40 new parishes within the four counties that now constitute the archdiocese of Newark. Most of them were in Bergen County and in the western areas of Essex and Union Counties. When new parishes did appear in the older cities, they generally were either national parishes or territorial parishes set up in expanding areas of the cities.

In the following decade, 1920-1930, only 19 new parishes opened, all but five of these before 1925, when the new laws had begun seriously to affect immigration. Only ten new parishes opened in the next decade, 1930-1940, the decade of the Great Depression. This tells only part of the story. By the 1920s and 1930s, many immigrant groups had moved into the second, third, and even fourth generations. Some, especially the Germans, lost much of their ethnic identity. The small “first churches” of the national parishes, often wood-frame, were replaced by majestic stone and brick edifices. Many national parishes opened parochial elementary and high schools. The “temporary” national parishes now were firmly established, often with elaborate parish buildings that sometimes were grander than the territorial parishes.

This edifice replaced a small wooden structure.

In New Jersey, the growth and the euphoria that surrounded the Church’s expansion masked underlying developments that provide a fuller, although not as optimistic, picture. These potential problems rarely were recognized particularly in the expansive spirit of the post-World War II era.

Immigration, Migration, and More Immigration

Pastoral Responses

The diocese faced the challenge of ministering to the first- and second-generation immigrants and providing priests and religious for this ministry. The immigrant communities, except for the Irish and eventually the Poles, did not provide enough priests from their populations. The very large Italian cohort was a source of great pastoral concern. Some Italian priests, diocesan and religious, came from Europe. Franciscans and other religious communities of Italian origin staffed parishes, but still there were not enough priests who were of Italian heritage or, at least, spoke Italian.

Bishop Walsh was aware of the “Great Migration” of African Americans. He established three personal parishes for African Americans: Queen of Angels (1930) in Newark, Christ the King (1930) in Jersey City, and Saint Peter Claver (1932) in Montclair. The main impetus for these parishes came from groups of African American Catholic women who continually petitioned for better pastoral care. When Walsh administered the sacrament of Confirmation at Christ the King in 1932, the number of confirmands was 223. By 1937, the number of parishioners reached 1,675. Queen of Angels flourished. Walsh baptized the 1,000th convert there in 1935. By the end of 1937, the total number of parishioners was 2,000.1

Bishop Walsh addressed the challenge of serving the ethnic communities in several ways. He encouraged the Religious Teachers Filippini to open schools and convents in the Italian parishes and he supported the establishment of their motherhouse in Morristown. Their first mission in the diocese of Newark began in 1929 at Mount Carmel Italian Parish in Newark. Walsh knew well these sisters from his time as bishop of Trenton. He equally supported other communities, such as the Polish Felician Sisters, who had come to the Newark diocese in 1895 to work in the Polish parishes, and the Sisters of Christian Charity who had worked in the German parishes since 1875.

In addition to the religious communities coming from overseas, several religious communities of women were founded in New Jersey to teach in the parochial schools and to work in hospitals and other apostolates. The two largest were the Sisters of Charity of Saint Elizabeth (Convent Station), an offshoot of the Sisters of Charity founded by Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, and the Dominican Sisters of Caldwell.

While there were numerous seminarians studying for the archdiocese, they did not reflect the national origins of the people of the archdiocese and their background did not prepare them to minister to the immigrants. In May 1938, the 141 seminarians represented, although not proportionally, the ethnic makeup of the dioceses of Newark and Paterson. Eighty, or 58 pecent, were of Irish heritage. Thirty-five were of Polish or Slavic background, 14 of German background. While Italians had become the largest ethnic group in New Jersey, only ten bore Italian names. There was a lone seminarian whose name indicated French heritage. One other had a Dutch name.

The effects of the slowdown of immigration during World War I and the subsequent anti-immigration legislation of the 1920s were apparent. All but four of the 141 were born in the United States. Two of the four foreign-born were Irish who had been born in England; one was born in Italy, and one in Czechoslovakia.

The 137 American-born seminarians overwhelmingly were born in the United States and from the local area. One hundred fourteen were natives of the dioceses of Newark and Paterson. Nineteen were by birth from the neighboring dioceses of New York; Brooklyn; Trenton; Albany; Hartford, Connecticut; and Philadelphia. Two had been born in Ohio, in Toledo and Cleveland. One was from Springfield, Massachusetts. The only one not born in the northeast was from Lafayette, Louisiana2. The local and native-born character of the seminarians would remain until the 1980s.

Since there were not enough priestly vocations from the various new ethnic communities, Archbishop Walsh addressed this pastoral problem by mandating language education in his seminary. Walsh, in his inimitable style, decided to attack the pastoral problem of language education by decree. In 1930, he ordered the creation of the Master School of Modern Languages at the Seminary. The details of this program are fascinating as they show the unique character of Archbishop Walsh.

Classes were held weekly in Italian, German, Lithuanian, Slovak, and Polish. The need for German was very small. The outburst of anti-German xenophobia during World War I (1917-1918) led to the German parishes dropping teaching in German in the parochial schools and severely limiting preaching in German.

In 1936, Walsh expended the Master School to include ecclesiastical students in Seton Hall High School and College, adding Arabic, Armenian, French, Hungarian, and Spanish. In a lengthy decree, he described this program in detail. Its goal was that every future priest would possess a “salutary, comprehensive, and certified reading, writing, speaking knowledge of a second modern language.” The students were expected to take the language of their heritage. At the time, it was normal practice to assign students of a particular ethnic background to national parishes of their ethnicity after ordination. Those of Irish or “American” background most often took Italian. The selection of the language, in Walsh’s words, “shall be deliberate, as it is unchangeable.”

In 1936, Walsh expended the Master School to include ecclesiastical students in Seton Hall High School and College, adding Arabic, Armenian, French, Hungarian, and Spanish. In a lengthy decree, he described this program in detail. Its goal was that every future priest would possess a “salutary, comprehensive, and certified reading, writing, speaking knowledge of a second modern language.” The students were expected to take the language of their heritage. At the time, it was normal practice to assign students of a particular ethnic background to national parishes of their ethnicity after ordination. Those of Irish or “American” background most often took Italian. The selection of the language, in Walsh’s words, “shall be deliberate, as it is unchangeable.”

With his attention to detail, he commanded that each student “possess, hold, and use” a dictionary, a grammar, a Bible, and a prayer book in the language studied, and to practice discourses and sermons in the language.” Walsh added, “May I recommend that every student look up every word in the dictionary signing the word looked up in every reference with the dot of a lead pencil. May I recommend that every student learn one new word every day during all his years of study?”3

Ideally, a newly ordained priest who had gone through the program from his first year of high school would have attained fluency in a modern language after twelve years of study. Despite the draconian and legalistic tone typical of Walsh, the program had obvious pastoral benefits. Walsh did not forget the deaf, assigning Father Stephen Landherr, C.Ss.R., as professor of sign language. Father Landherr would serve until the 1970s, when Reverend John Hourihan replaced him.

In 1936, two seminarians were studying Lithuanian, eight German, 13 Polish, and three “Slavish.” Seventy-two were studying Italian, five of them of Italian origin, the others of Irish or “American” backgrounds.4 The number of seminarians of Italian background never equaled the need for service to the large Italian American immigrant population. The Master School of Modern Languages, a deliberate program to provide pastoral care to the immigrant population of the era, continued until the 1960s, when seminary programs concentrating on Spanish took its place.

The continued importance of ethnic pastoral care is evident in the number of national parishes in the archdiocese in 1938, the year that Passaic, Morris, and Sussex counties became the new diocese of Paterson, leaving the new archdiocese with Bergen, Hudson, Essex, and Union counties. Of the 185 parishes in the new archdiocese, 68 were officially national parishes. Another six to ten parishes, although technically territorial, were predominantly populated by one ethnic group. Sixteen of the 34 parishes in Newark and eleven of the 26 in Jersey City were national parishes. Twenty-nine national parishes were Italian, 15 were Polish, and 14 were German.5

In the next decade to 1950, the Catholic population of the archdiocese climbed from 645,000 to 1,028,951, while the total population inched from 2,227,370 to 2,490,663.6 Clearly many non-Catholics were leaving the area and being replaced by Catholics, both Euro-Americans and Latinos, chiefly Puerto Ricans. Within the archdiocese, Hudson County began a decline in population that did not turn around until recent years.7

Suburbanization and a new Archdiocese

In Newark

A major change in New Jersey during this “pause” was increasing suburbanization. Suburban growth and concurrent urban decline began in the 1920s, slowed during the Depression of the 1930s, but escalated after World War II. This trend initially was so gradual that it hardly was noticed but, after World War II, it increased rapidly. The G.I. Bill provided low-rate home loans and education loans to returning veterans, many of whom eschewed the crowded urban lifestyle of their parents and chose to reside in the suburbs.

In doing so, they left the urban ethnic enclaves, often disparagingly called “ghettos,” for the lawns of suburbia. This meant leaving the self-contained world of the Catholic parish that provided religious, educational, social, recreational, and other aspects of daily life often with little contact with non-Catholics. This “Catholic world” was replaced with a religiously, educationally, and ethnically diverse suburban world. This new world required many adjustments that raised issues of Catholic identity.

With the establishment of Newark as an archdiocese in 1937, and the creation of the dioceses of Paterson and Camden, we can now speak of the archdiocese of Newark within its current boundaries. The small area of the archdiocese of Newark, about 500 square miles, and its location at a major port of entry, have made it subject to rapid demographic changes.

The major archdiocesan growth of this period was in the suburbs of Bergen County and western Essex and Union Counties. The surrounding dioceses of Paterson and Trenton, which then included the Metuchen Diocese, experienced similar, if not greater, growth. There was internal migration within the four counties. Many Hudson County residents moved to Bergen County while urban residents of Essex and Union moved into the western portions of these counties. In addition, numerous Catholics from the New York and Brooklyn dioceses moved to the Newark archdiocese, especially to Bergen County.

The major archdiocesan growth of this period was in the suburbs of Bergen County and western Essex and Union Counties. The surrounding dioceses of Paterson and Trenton, which then included the Metuchen Diocese, experienced similar, if not greater, growth. There was internal migration within the four counties. Many Hudson County residents moved to Bergen County while urban residents of Essex and Union moved into the western portions of these counties. In addition, numerous Catholics from the New York and Brooklyn dioceses moved to the Newark archdiocese, especially to Bergen County.

The suburban expansion of the archdiocese of Newark was not without a price—the decline of the urban parishes. Several government policies drove this transition. Beginning in the 1930s, but increasing after World War II, federal and state authorities, seeking to end urban “blight,” bulldozed entire city blocks. The homes on these blocks, mostly row houses, were replaced, either with housing projects or with government and educational buildings.

In the name of progress and urban renewal, numerous city parishes were decimated. Construction workers literally drove through neighborhoods and replaced thousands of homes with six-to-eight lanes of highway. The New Jersey Turnpike, completed in 1952, and the Garden State Parkway, completed in 1957, further accelerated suburbanization and urban decline.

These new toll roads linked the northern and southern portions of the state and provided easy access to the New Jersey shore. East-west Interstate Highways 78 and 80, completed in the 1970s, provided similar access to the western parts of the state. Strangely, many folks did not notice but so-called urban renewal programs and highway construction left behind shattered neighborhoods. These depressed highways splintered parishes and dispersed parishioners. Where Interstate 280 crossed the Garden State Parkway, these two highways split the city of East Orange into four quadrants and devastated not only the Catholic parishes in that city but its urban life as well.

Tens of thousands of parishioners left the cities, especially Newark, Jersey City, Orange, East Orange, Irvington, and Elizabeth. While many relocated in Bergen County and in other suburban areas, large numbers relocated outside the territorially small archdiocese. As they left the cities, a rich heritage of urban life and ethnic communities disappeared.

This traumatic change is summarized in the on-line history of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish in Orange.

In 1973 work was completed on Interstate Highway 280 which cuts just along the north face of the church. Due to the construction, about 800 parish families lost their property or moved to other areas of Orange and West Orange. The 1970’s and 80’s witnessed other changes in the neighborhood, as older Italian families began to move to other suburbs such as East Hanover and Livingston, while the Oranges were populated by newer immigrant groups from Africa, the Caribbean Islands, and Latin America.8

On the surface, all appeared to be well. Throughout the 1950s, in almost every issue, the Catholic press showed the archbishop of Newark blessing a new church, grammar school, high school, rectory, or convent. The increased prosperity of New Jersey Catholics fueled the institutional expansion of the latter part of the episcopates of Bishop O’Connor (1902-1927 – 93 parishes), of Archbishop Walsh (1928-1952 – 30 new parishes), and of Archbishop Thomas Boland (1953-1974 – 31 new parishes). Bishop O’Connor’s tenure encompasses the height of immigration and the beginning of its decline. Of the 93 parishes he opened, about 35 were national parishes or focused on the care of a specific ethnic group.

Catholic schools expanded, reaching their peak enrollments in the 1960s. In 1960, Catholic elementary schools in New Jersey counted almost 128,000 pupils; Catholic high schools almost 21,000.9 It is not surprising that Church leaders saw a limitless future. No one could imagine what lay ahead.

Many saw the 1960 election of John F. Kennedy, the first Catholic president, as a sign that Catholics had “arrived.” In many ways, they had arrived. Their social and economic status had never been higher. More were college graduates than ever before. Many Catholic leaders, including the venerable John Tracey Ellis, dean of American Catholic Church historians, shared this optimism. Ellis later would temper his enthusiasm.

When Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council in 1962, Catholics rejoiced. The open and joyful spirit of Pope John XXIII raised Catholic spirits and strengthened their faith in a future of endless possibilities.

Young Catholic families were happy to leave crowded cities for suburban lawns and backyards, but suburban Catholic growth had a negative side: the collapse of urban Catholic life and of urban parishes. For a century, the urban parishes had supported Catholic faith and provided the glue that held Catholic culture together. Each parish was a significant social unit important to all the families that composed it. It was the community center, the school, and the center of faith. The great majority of vocations to the priesthood and religious life in the archdiocese of Newark came from the city parishes. The shrinking of these parishes and the events of the 1960s ended that phenomenon.

The First Spanish-Speaking Arrivals

The first clearly discernable Spanish presence in northern New Jersey is manifest in the 1920s. The Spanish immigrants to the United States in the 1910s and 1920s often are called the “forgotten Spanish diaspora.” These folks mostly came from northern Spain and settled in the port area of Newark and Elizabeth. By 1923, they gathered for Mass in the lower church of Saint Patrick’s Church in Elizabeth. More Spanish came in the 1930s to escape the chaos of the Spanish Civil War. At the same time, immigrants from Portugal began to arrive and settle in the Ironbound section of Newark. As Europeans, the Spanish and Portuguese were able to enter as legitimate immigrants under the quota system.

In 1926, Saint Joseph’s Spanish-Portuguese parish was established in the Ironbound section of Newark. Third Order Regular Franciscans (T.O.R.) from the Spanish island of Mallorca served the parish. Bishop Walsh dedicated the remodeled Saint Joseph’s Church on December 9, 1928. In recognition of Walsh’s assistance to the Spanish community, King Alfonso XIII of Spain named him a Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Isabella the Catholic on July 2, 1929. Portuguese immigration grew after World War II and, in the late 1950s, a separate Portuguese parish, Our Lady of Fatima, was formed. Its name was changed to Immaculate Heart of Mary in 1965.

The priests from Saint Joseph’s Parish in Newark also served the Spanish community in Elizabeth at Saint Patrick’s Church. In 1947, the archdiocese established Immaculate Heart of Mary Spanish-Portuguese Parish in Elizabeth. In 1954, the Religious Teachers Filippini came to the parish where they provided religious education as well as a day care center. In 1973, a separate Portuguese parish was formed in Elizabeth, also named Our Lady of Fatima.

The first phase of Iberian migration had followed the established pattern. The immigrants from Spain and Portugal came to a particular section of a city. A national parish was established, served by priests from the “old country.” Sometimes the new parish was given the church and other buildings of a declining parish. This practice of creating national parishes preserved much of their cultural heritage as the immigrant entered American society. The national parish, the societies, the local social clubs, provided an atmosphere of security, stability, and support for the Spanish and Portuguese Americans of the Ironbound and of Elizabeth Port. At the same time, American seminarians were learning some Spanish and Portuguese with the goal of ministering among this population.

It was inevitable that the diocese established separate parishes for the Spanish and Portuguese. Placing these two nationalities in the same parish demonstrated that the diocesan authorities did not understand the widely different cultures of Spain and Portugal.

Simultaneously, in Newark and elsewhere in the archdiocese, individual parishes were becoming “multi-cultural” before the word was fashionable. Many parishes experienced a continually shifting ethnic makeup, a phenomenon that would become common in years to come. This gradual change in the makeup of an existing parish, combined with providing pastoral care for the new language-groups, replaced the traditional national parish approach to new immigrant groups.

Refugees and Migration from Puerto Rico

After World War II, Catholic Charities that took up the work of resettling refugees in the archdiocese. From 1953 to 1965, in addition to normal immigration and migration, over 8,500 refugees from Communist governed countries settled in North Jersey. In 1956-1957, Catholic Charities assisted some 1,235 refugees of the Hungarian Revolution in finding shelter here. Approximately another 3,000 from Europe and Indonesia received assistance in settling here as changes in the law eased their entry into the United States.10 These numbers, although significant, were rather small amid the Spanish-speaking influx of new residents.

Most of the “new” Catholics coming to northern New Jersey after World War II were Spanish-speaking Catholics from Puerto Rico. As citizens since 1917, they were not subject to the restrictive immigration laws enacted in the 1920s. Inexpensive air travel made this migration possible.

In the 1950s, the number of Puerto Ricans coming to the archdiocese markedly increased and a new pattern of pastoral care emerged that set the tone for the next half-century. Puerto Rico never had produced many native-born priests but relied on priests from Spain and then from the United States. Several priests began Spanish-language studies on their own and the archdiocese began to encourage and support Spanish language studies for priests and seminarians.

In the 1950s, the number of Puerto Ricans coming to the archdiocese markedly increased and a new pattern of pastoral care emerged that set the tone for the next half-century. Puerto Rico never had produced many native-born priests but relied on priests from Spain and then from the United States. Several priests began Spanish-language studies on their own and the archdiocese began to encourage and support Spanish language studies for priests and seminarians.

Most of the Puerto Rican migrants were poor and settled in Newark and Elizabeth as well as in Hudson County. Many of the urban parishes in the archdiocese had lost numerous parishioners to the suburbs and there was more than enough room and more than enough facilities available. Little by little, they joined and gave new life to existing parishes and, in time, some of these parishes became majority Spanish-speaking.

A Pastoral Response

The archdiocese did not establish national parishes specifically for Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican Catholics. The Puerto Ricans tried to “blend” into the existing parishes that were decreasing in members. The transition was not always easy. As a century before, English-speaking parishes and parishioners did not always welcome the new folks. Many, but not all, forgot that their grandparents and parents faced similar challenges.

When it celebrated its centennial in 1950, Saint Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral exemplified the gradually shifting ethnic patterns of the times. Many still regarded Saint Patrick’s as an “Irish” parish, but that had not been an accurate designation for decades. In the 1930s, half the parish was Italian; in the 1940s, the school enrollment, normally about 300, included students born in America, Ireland, Italy, England, Scotland, Germany, Greece, Portugal, Poland, and Spain. In the 1950s, Saint Patrick’s sponsored the first Hispanic Girl Scout Patrol in the city of Newark.

By the 1960s, Puerto Ricans constituted one-third of the parish. Saint Patrick’s was the first parish, other than those established for the Spanish and Portuguese, in the Archdiocese of Newark to have an organized Hispanic Apostolate. The parish began its first Spanish Mass in 1954, when Father Gennadius Diaz, O.S.B., of Newark Abbey, came to preach in Spanish and developed congregational singing in Spanish. Father Placid Alvarez, O.S.B., soon joined him. Father Placid taught classes in English, assisted by Marguerite McLaughlin and by Mrs. Blake, a Berlitz School of Languages teacher.

The pastor of Saint Patrick’s, Msgr. James F. Looney, chancellor of the archdiocese, encouraged the ministry to the Hispanic population. It was providential that a major official of the archdiocese undertook this pastoral initiative. Archbishop Boland assigned Rev. Thomas W. Heck, who had studied Spanish in Puerto Rico, as assistant pastor in 1959. Religious instruction and church services in Spanish became part of the parish program. The 11:00 a.m. Sunday Mass became “La Misa Hispana” and the new parishioners formed Hispanic church societies and conducted various church socials that drew the community together. The Hispanic ministry at Saint Patrick’s served as a model for many other parishes. The Puerto Rican presence would continue to grow until the development of the Rutgers University campus within the parish displaced hundreds of parishioners.

The Saint Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral experience mirrored that of the archdiocese, particularly in its urban centers. The ethnic makeup of the entire population was changing. Most of the migration out of the archdiocese was composed of Catholics of European heritage—Irish, Italian, Polish, German, Slovak, and so forth. At the same time, the cities experienced the influx of large numbers of African Americans who were leaving the southern states in the “Great Migration” in search of a better life. Comparatively few African Americans were Catholic but there were quite a few “new” Catholics among the Spanish-speaking.

The new migrations and immigrations foreshadowed the radical ethnic transformation of the archdiocese of Newark that would take place in the closing decades of the twentieth century after the passage in 1965 of the Hart-Celler Immigration and Nationality Act.

The Flight of the Cubans

The last large wave of immigrants during the “pause” was from Cuba. After the Communist revolution of Fidel Castro in Cuba, refugees from that unfortunate island flocked to New Jersey. Accompanied by Cuban priests in many cases, they settled mostly in Hudson County. Because of the failed United States intervention in Cuba, the federal government granted them special status as refugees rather than as immigrants under the then-current laws.

Prior to the Cuban Revolution there was a small community of about 2,000 Cuban immigrants living in Union City, who had originally arrived in the 1950s. In the immediate aftermath of the Castro Revolution, the initial exodus (1959–1962) of Cubans to the United States were mostly members of Cuba’s educated middle class, and most arrived between the beginning of the revolution and the mid-1960s.

Special Patroness for Cuban Refugees

Note the boat beneath the image of Our Lady,

A Symbol of the Refugee’s Voyage

Hudson County was the preferred destination for many Cuban refugees and soon became the main center for Cuban American culture. As they moved into the area, they were able to purchase homes and business from those inclined to leave for the suburbs. Their rapid increase was astounding. By 1965, Catholic Charities had assisted about 5,000 Cuban refugees in the archdiocese.11 By 1970, 59 thousand Cubans lived in New Jersey. By 1980, the number had grown to 68 thousand.12

The first post-World War II wave of Puerto Rican migration had set the pattern for the pastoral care of the newly arrived Spanish-speaking Catholics. The migrants arrive and soon become a recognizable group in the community. The local parish seeks to serve them just as previous new groups in the past. The children enter the parochial school. Eventually the parish offers religious services in Spanish, celebrated either by a resident priest who had studied and learned Spanish or by a priest from nearby, often a member of a religious community. Soon priests from Latin America come to the archdiocese as well. Parish societies are established, and cultural events and festivals follow soon after.

In the next decade, the wave of immigration became a flood. Some parishes seemed to become entirely Spanish-speaking almost overnight. The archdiocese gradually created new offices and ministries to meet new needs. However, the basic post-World War II pattern of parochial absorption of new immigrants remained to serve the Hispanics.

By the end of the 1960s, it was clear that the Hispanic population had increased to such a degree that further archdiocesan organization and coordination was necessary. In 1970, Archbishop Boland named Father Thomas Heck as first Vicar for Hispanics. A centrally organized Hispanic Apostolate was now in place at the archdiocesan level.

By the end of the 1960s, it was clear that the Hispanic population had increased to such a degree that further archdiocesan organization and coordination was necessary. In 1970, Archbishop Boland named Father Thomas Heck as first Vicar for Hispanics. A centrally organized Hispanic Apostolate was now in place at the archdiocesan level.

In 1965, the archdiocese focused on the episcopal anniversary of Archbishop Thomas Boland, a beloved shepherd who had guided the archdiocese through a period of great institutional expansion in the suburbs of the archdiocese. 1965 also saw the last session of the Second Vatican Council. That same year, the booklet commemorating the 25th anniversary of the episcopal consecration of Archbishop Boland summarized the situation of the Spanish-speaking Catholics of the archdiocese at that time.

The problem of immigration is one that has troubled and blessed the Church in the United States for well over a century. The post-war period has seen the arrival in the Archdiocese of Newark of many immigrants who have been more or less absorbed by the existing national communities. At present, Spanish-speaking Catholics from Cuba and Puerto Rico are the largest new group. It is estimated that there are somewhere in the neighborhood of 21,000 Cubans and 75,000 Puerto Ricans in the Archdiocese. More than twenty priests, religious and secular, are serving these people wherever they live and in the two parishes and one center designated especially for the Spanish speaking. Two orders new to the Archdiocese, the Vocationist Fathers and the Recollect Augustinians, have come to aid in this apostolate. Another worthwhile development is the Cursillo Movement, which had its origin in this work. The needs of the Portuguese community in Newark have also been recognized by the establishment of Our Lady of Fatima Parish.13

The authors of this commemorative booklet had no idea of what the future would bring.

Another extremely important event occurred that same year. On October 3, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson went to Liberty Island, and in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, signed The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 also known as the Hart–Celler Act. More than likely, this ceremony and this new law drew little attention; but its effects would transform the United States, the Catholic Church, and the archdiocese of Newark in unimaginable ways.

A Sad Footnote – Mexicans, Latin Americans, and “Operation Wetback”

It is ironic that, during this period and the decades before it, the southern border was rather porous. Many Mexicans passed into the United States for work and most returned home after the work season. However, in the 1940s and 1950s, growing numbers of Mexican workers crossed the border to work in the United States to the dismay of the Mexican government. Mexico was annoyed because their developing industries needed laborers. This led to a sad episode in American history that, unfortunately, highlighted the attitude of many Americans to immigration that we see repeated today.

First, a cooperative effort of the United States and Mexican governments called the “Bracero” program tried to moderate this traffic. It allowed large numbers of Mexican workers to enter the United States for work and offered the protection from unfair labor practices. When it failed, the United States immigration authorities, in cooperation with the Mexican government in 1954, initiated the largest mass deportation in American history, entitled “Operation Wetback,” to return illegal Mexican workers to their homeland. Yes, it was officially called “Operation Wetback.”

As many as 1.3 million people may have been swept up in the Eisenhower-era campaign with a racist name, which was designed to root out undocumented Mexicans from American society. The short-lived operation used military-style tactics to remove Mexican immigrants—some of them American citizens—from the United States. Though millions of Mexicans had legally entered the country through joint immigration programs in the first half of the 20th century, Operation Wetback was designed to send them back to Mexico.

With the help of the Mexican government, which sought the return of Mexican nationals to alleviate a labor shortage, Border Patrol agents and local officials used military techniques and engaged in a coordinated, tactical operation to remove the immigrants. Along the way, they used widespread racial stereotypes to justify their sometimes brutal treatment of immigrants. Inside the United States, anti-Mexican sentiment was pervasive, and harsh portrayals of Mexican immigrants as dirty, disease-bearing and irresponsible were the norm.

Mass deportations of Mexican immigrants from the U.S. date to the Great Depression, when the federal government began a wave of deportations rather than include Mexican-born workers in New Deal welfare programs. According to historian Francisco Balderrama, the U.S. deported over 1 million Mexican nationals, 60 percent of whom were U.S. citizens of Mexican descent, during the 1930s.

For many Mexican Americans even today, “Operation Wetback” continues to bring back memories of a fearful historical moment they don’t want to relive.14

«I. How We Became Who We Are« : »III. The “New” People of Newark A New World – A Microcosm of the Universal Church»

Footnotes

- George A. Reilly, “Thomas J. Walsh,” in The Bishops of Newark, South Orange NJ, 1978, 108.

- Compiled from statistics in Visitation Report of Immaculate Conception Seminary, Visitatio Apostolica Seminariorum—1938, in AICS 8.3.1.

- Robert J. Wister. Stewards of the Mysteries of God: Immaculate Conception Seminary 1860-2010, Immaculate Conception Seminary, South Orange NJ. Pp.167-168.

- Minutes of the Board of Deputies of Immaculate Conception Seminary, June 8, 1936, in AICS 2.1.1.

- Official Catholic Directory, P.J. Kenedy and Sons, 1939.

- Official Catholic Directory, P.J. Kenedy and Sons, 1939, 1950; United States Census Bureau, 1940 and 1950.

- United States Census Bureau, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1990, 2010.

- https://olmcorange.com/parish-history

- The Official Catholic Directory 1960.

- Booklet Commemoration of The Silver Jubilee of the Episcopal Consecration of His Excellency The Most Reverend Thomas A. Boland, S.T.D. Archbishop of Newark 1940 – 1964 Wednesday, the twenty-third of June Nineteen hundred and sixty-five, p. 37

- Commemoration of The Silver Jubilee of the Episcopal Consecration of His Excellency The Most Reverend Thomas A. Boland, S.T.D. Archbishop of Newark 1940 – 1964 Wednesday, the twenty-third of June Nineteen hundred and sixty-five, p. 37.

- Hernández, Roger E. Cuban Immigration. 2003, p. 12-26, Mason Crest Publishers, Broomall PA

- Commemoration of The Silver Jubilee of the Episcopal Consecration of His Excellency The Most Reverend Thomas A. Boland, S.T.D. Archbishop of Newark 1940 – 1964 Wednesday, the twenty-third of June Nineteen hundred and sixty-five, p. 37.

- Erin Blakemore, “The Largest Mass Deportation in American History,” https://www.history.com/news/operation-wetback-eisenhower-1954-deportation.