Rev. Robert J. Wister, Hist.Eccl.D.

Immaculate Conception Seminary

Seton Hall University

Introduction

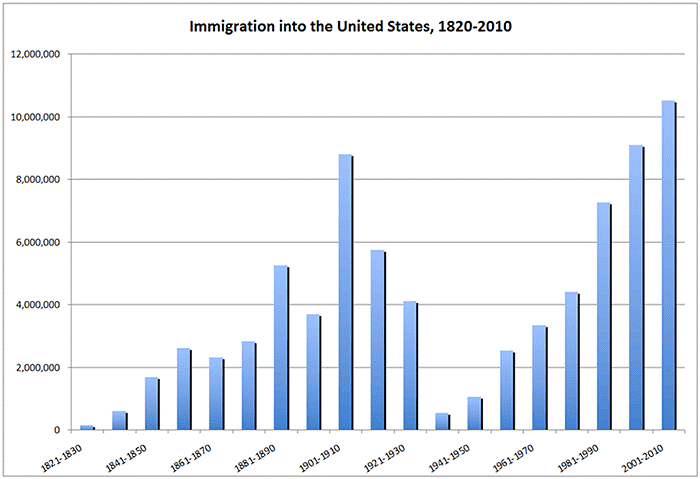

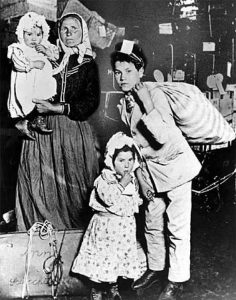

Immigrants established the Church in New Jersey and have sustained it for more than three centuries. Most of these immigrants arrived in two waves separated by an interim period of light immigration. Immigration to New Jersey began long before the establishment of the diocese of Newark. It was the major factor leading to the creation of the see. The first great wave of immigration extended roughly from 1840 to 1920. A “pause” in immigration lasted from 1920 until 1965 when the second wave began.

These periods, these “waves of immigration,” had similarities and differences. There were more similarities than differences. In retrospect, the interim period between the two “waves” appears quite placid, although it was not. It marked the beginning of a vast Latino migration into the archdiocese.

The following patterns characterize both waves of immigration and, to some extent, the “pause:”

- Immigration was simultaneously multiethnic, from many countries, not one;

- Many pastoral initiatives came from groups of lay men and lay women;

- Ethnic-based or “national” parishes were a significant part of pastoral care;

- Immigrant priests and religious sisters served most, but not all, immigrant groups;

- Large numbers of priests and sisters from religious communities and orders engaged in pastoral parish work;

- Continuing progress in the technology of transportation facilitated immigration;

- There were diverse motivations for migration, one constant being a desire to improve the lot of the family;

- Immigrants often were not welcomed, even by their fellow Catholics, and

- Various political and economic crises, as well as famines and natural disasters, encouraged people to migrate.

In these essays, I plan to review the immigration experience and the pastoral response of the Church in New Jersey. This will help us to understand where we are now and how we arrived here; and even more importantly, who we are and how we are the local Church of Newark.

The First Catholics in New Jersey

The Colonies of East and West Jersey did not welcome Catholics. At best, they tolerated them. In the early 18th century, Catholic laborers came from Germany to work in the new iron and glass industries in southern New Jersey. They crossed the Delaware River to attend Mass in Philadelphia. Catholics in the northern part of the state travelled by ferry across the Hudson to attend Mass in Manhattan. In addition, Jesuits from Saint Joseph’s Church in Philadelphia and circuit riding priests such as Ferdinand Steinmeyer, known as “Father Farmer,” cared for their spiritual needs. Father Farmer’s registers include Irish, English, French, and German names. The primary characteristic of the Catholic Church in New Jersey was present from the first years; it was a multi-ethnic church.

After independence, New Jersey maintained its anti-Catholic attitude. Its 1776 state constitution continued the colonial practice of restricting state offices to Protestants. A later state constitution finally removed this provision in 1844.

Modest numbers of French Catholics fleeing the anti-religious turmoil of the French Revolution that began in 1789 added to the number of Catholics in New Jersey. A few Irish rebels escaping after the abortive United Irishmen Rebellion of 1798 arrived soon after. The numbers were not great, and they would not increase until the political situation in Europe settled after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

In the United States, the early 1800s were a time of rapid industrial and commercial development. This expansion needed workers. It immediately attracted Catholic immigrants from Germany and Ireland who worked on the construction of railroads and canals, and in the new factories.

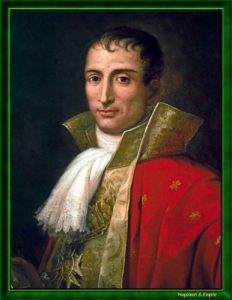

King of Naples (1806-1808)

King of Spain (1808-1813)

Probably the most famous immigrant and New Jersey resident of the time was Joseph Bonaparte, former King of Naples and Spain, and elder brother of Emperor Napoleon I. He lived in Bordentown from 1817 to 1832.

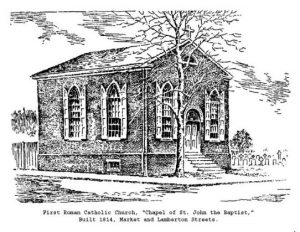

By 1814, the number of Catholics in Trenton had increased sufficiently to build a small church. Its origin is rather curious. Neither an immigrant group nor a diocese built the first church in New Jersey, Saint John the Baptist. Artist and businessman Giovanni Battista Sartori provided the funds to build the church. A successful executive, he lived in the Trenton area and served as a papal diplomat, the papal consul in Philadelphia. Thus, a layman, who eventually returned to his native Italy, built the first church building in New Jersey, naming it after his own patron saint. He was a true entrepreneur. The records of one of his enterprises show that he sold macaroni to Thomas Jefferson.

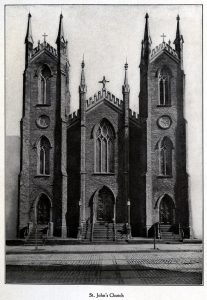

About ten years later, in 1826, Newark’s first parish, Saint John’s, was established. The genesis of the first church in Newark followed a more conventional pattern. Newark Catholics had been meeting in private homes where an itinerant priest celebrated Mass. They formed a corporation called “Saint John’s Church.” They petitioned the bishop of New York, who then had jurisdiction over northern New Jersey, for a priest and he sent Father Gregory Pardow to them. Under his direction, the first church in Newark was built in 1827-1830. It was enlarged by his successor, Father Moran, in 1840. Most of the Saint John’s parishioners were of Irish heritage.

The First Wave of Immigration 1840 – 1920

The Irish and the Germans

European immigration in increasing numbers began after the turmoil of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars had subsided by 1820. The majority came from Germany and Ireland.

Beginning in the 1840s, immigration to New Jersey increased dramatically. Initially, about 80 percent of the new arrivals, like those just before, were from Germany and Ireland. They supplied needed workers for the state’s growing industries.

Nineteenth century technological progress in transportation facilitated immigration. Larger, faster, and safer passenger ships moved across the ocean in shorter time and with increasing frequency. Then, and in the future, advances in transportation would facilitate immigration.

The Mass Irish Immigration and the German Immigration

As always, diverse motivations spurred immigration. Political instability, economic opportunity, and occasional religious persecution stimulated German immigration. On the other hand, the Irish came mostly out of desperation. In the 1840s, a blight destroyed the potato crop in Ireland. The resultant famine, the “Great Hunger,” killed over one million persons and drove more than one and a half million Irish to emigrate. This pattern, immigration fueled by human tragedies overseas, was replicated in the future.

As always, diverse motivations spurred immigration. Political instability, economic opportunity, and occasional religious persecution stimulated German immigration. On the other hand, the Irish came mostly out of desperation. In the 1840s, a blight destroyed the potato crop in Ireland. The resultant famine, the “Great Hunger,” killed over one million persons and drove more than one and a half million Irish to emigrate. This pattern, immigration fueled by human tragedies overseas, was replicated in the future.

From 1820 to 1860, 1,956,557 Irish arrived in the United States, 75 percent after 1845. About 85 percent of the Irish immigrants were Catholics.1 Irish migrated all over the world, but the majority of Irish immigrants came to the United States, tens of thousands to New Jersey, chiefly northeastern New Jersey. By 1850, the foreign-born population of New Jersey included over 31,000 Irish, most of them Catholic, and over 10,000 Germans, many Catholics among them.

By the mid-1840s, there were over 1,500 Catholics, German and Irish, in the city of Newark. This sudden increase in the Catholic population of Newark strained the facilities of Saint John’s Church on Mulberry Street. In 1842, Saint Mary’s Parish (now Newark Abbey) was established to care for the growing German population of Newark.

By the mid-1840s, there were over 1,500 Catholics, German and Irish, in the city of Newark. This sudden increase in the Catholic population of Newark strained the facilities of Saint John’s Church on Mulberry Street. In 1842, Saint Mary’s Parish (now Newark Abbey) was established to care for the growing German population of Newark.

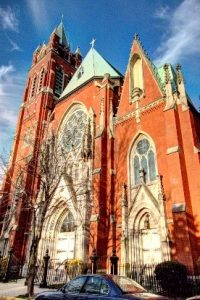

This relieved the pressure on Saint John’s, but the enormous Irish immigration required additional measures. After proposals to enlarge the church failed, Rev. Patrick Moran, pastor of Saint John’s, decided to build a new church.

In 1850, shortly before the establishment of the diocese of Newark, the bishop of New York created the city’s third parish, Saint Patrick’s (Pro-Cathedral), out of Saint John’s to meet the needs of the growing Irish population in Newark. These three parishes set the stage for the enormous growth of the future. They also established a pattern of recognizing the immigrant cultures and addressing the pastoral needs of the immigrants through providing distinct churches to meet the pastoral needs of specific ethnic groups, in the case of Saint Mary’s, the Germans; Saint Patrick’s, the Irish. Most of the territorial parishes continued principally to serve the Irish population. In time, Catholics in New Jersey called them the “Irish parishes.” So-called “national parishes” served the successive ethnic groups. Some parishes, from their beginning, included more than one ethnic group; others would later develop in a multi-ethnic direction.

The influence of lay groups, like those who in Saint John’s who petitioned for a priest, would continue as various new ethnic and racial groups brought their needs to the attention of the bishop.

The Diocese of Newark

In 1850, the year Saint Patrick’s Church opened, the bishops attending the American Church’s Seventh Provincial Council recognized the mushrooming immigrant Catholic population. They recommended to Rome the creation of several new dioceses, among them, Newark.

James Roosevelt Bayley took possession of his diocese as the first bishop of Newark in 1853. The new diocese encompassed the entire state of New Jersey. The best estimates at the time counted approximately 30,000 Catholics in the new see, most of Irish and German birth, and concentrated in the northeastern part of the state. There were four churches in Newark, nine others in what would become the four-county archdiocese of Newark almost a century later.

In his see city, Bayley found four churches; Saint John’s, established in 1827, Saint Mary’s in 1846, Saint Patrick’s in 1848 (opened in 1850), and Saint Joseph’s, in 1850. Saint Mary’s served a predominately German congregation while Saint John’s, Saint Patrick’s, and Saint Joseph’s were mostly Irish in their membership. Saint Joseph’s also had a significant number of German parishioners.

In 1857, at Bishop Bayley’s invitation, three German-born monks from Saint Vincent’s Archabbey in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, took charge of Saint Mary’s parish. They established a Benedictine monastery and, in 1868, Saint Benedict’s College (Prep).

The story of Saint Mary’s presents some of the characteristics of many of the immigrant churches of Newark. It is a parish established for a specific ethnic group and foreign-born priests serve the needs of their co-nationals.

It is notable that the priests of Saint Mary’s are members of a religious community. While this is not extraordinary, the Newark diocese from its beginning welcomed religious communities, often from overseas, to serve the pastoral needs of both ethnic and territorial parishes.

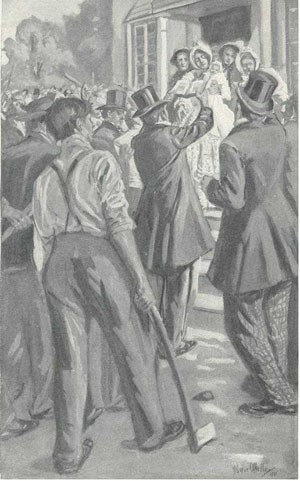

She dared the Protestant rioters to harm her or her baby and they dispersed.

The child in her arms eventually was ordained a priest and became the Rector of Saint Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral in Newark.

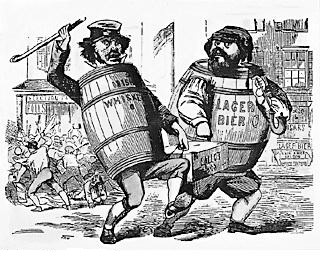

Anti-Catholicism was endemic to the United States in the mid-19th century. The so-called “American Party,” known as the “Know-Nothings” because when asked about their beliefs, its members, responded, “I know nothing,” saw immigrants as a danger to their definition of American identity and values.

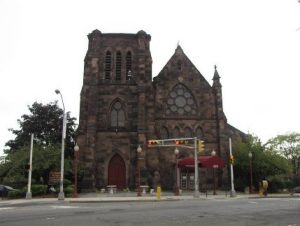

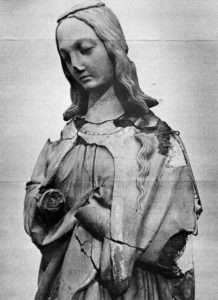

On September 5, 1854, the Orange Association, also known as the American Protestant Association, marched 3,000 strong through Newark. They attacked and looted Saint Mary’s Church (Newark Abbey) on High Street. Within Saint Mary’s, a damaged statue of the Blessed Virgin remains as mute reminder of this outrage. The sisters at Saint Patrick’s gathered the orphans into the church, locked the doors and remained there through the night. Father McQuaid, the rector, walked among the crowds and did his best to persuade angry Catholics to disperse. Later, he unsuccessfully demanded prosecution of the attackers, but succeeded in seeing responsibility for the violence placed on the Orangemen.

On September 5, 1854, the Orange Association, also known as the American Protestant Association, marched 3,000 strong through Newark. They attacked and looted Saint Mary’s Church (Newark Abbey) on High Street. Within Saint Mary’s, a damaged statue of the Blessed Virgin remains as mute reminder of this outrage. The sisters at Saint Patrick’s gathered the orphans into the church, locked the doors and remained there through the night. Father McQuaid, the rector, walked among the crowds and did his best to persuade angry Catholics to disperse. Later, he unsuccessfully demanded prosecution of the attackers, but succeeded in seeing responsibility for the violence placed on the Orangemen.

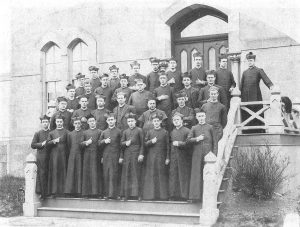

Early Clergy and First Churches

In the Archives of Immaculate Conception Seminary, there are letters of status for the priests of New Jersey at the time of the establishment of the diocese in 1853. Almost all are foreign-born. Throughout the first half-century of the diocese, the first bishops of Newark, Bayley, Corrigan, and Wigger actively recruited seminarians and priests, chiefly from Ireland and Italy. The two most prominent priests of the new diocese, Januario de Concilio and Bernard McQuaid, were foreign-born, from Italy and Ireland respectively.

From its foundation, Newark was a diocese of immigrants mostly served by immigrant priests. While some immigrants from every group scattered around the state, most crowded into the northeastern counties. In the 1850 census, Bergen, Hudson, Essex, and Union Counties alone accounted for almost half of the immigrant population of the state. (29,812 of 59,948). The census also informs us that, in 1850, there were 50 slaves in these four counties, 41 of them in Bergen County.

Thirteen of the 30 churches in New Jersey at the time of the establishment of the diocese of Newark in 1853 were in the northeast part of the state that would become the archdiocese of Newark. They were:

1826 – Saint John, Newark

1831 – Saint Peter, Jersey City (Now part of Saint Peter’s Prep)

1837 – Saint Peter, Belleville

1842 – Saint Mary, Newark Abbey

1844 – Saint Mary of the Assumption, Elizabeth

1848 – Saint Patrick Pro-Cathedral, Newark

1850 – Saint Joseph, Newark (Closed)

1851 – Our Lady of Grace, Hoboken

1851 – Saint John, Orange

1851 – Saint Mary, Plainfield

1851 – Saint Michael, Union City (Merged with Saint Joseph)

1852 – Saint Michael, Elizabeth (Merged with Holy Rosary)

1852 – Saint Rose of Lima, Short Hills

The National Parish as a Pastoral Policy

Seventy years later, in 1920, 58 percent of immigrants in New Jersey lived in the four counties that would become the archdiocese of Newark. The distribution of immigrants remains similar today. According to the 2010 census, immigrants constituted 22 percent of the state population, while 45 percent of all immigrants in the state live in the archdiocese of Newark.

The non-Catholic majority of Americans did not welcome Catholic immigrants. Not only did the non-Catholics disparage the religion of the immigrants, the financially successful among them assumed that because the immigrants were poor, foreign, and different, that meant they were also dirty, dangerous, and lazy. Many working-class people regarded the immigrants as competitors for jobs, homes, and social prestige that they believed rightly belonged to them.

There also were strains between the different Catholic ethnic groups. German and Irish tensions were a hallmark of late 19th century American Catholicism. German American Catholics refused to give up their language in devotions, parochial schools, and public religious events. The Catholic hierarchy, by this time predominately Irish American, viewed this as provoking antagonism against Catholics by the Protestant majority, who saw retention of the home language as “un-American.” They pressured the Germans to give up using their native language in devotions and sermons and more rapidly to assimilate to the predominant culture.

Newark Abbey

The German and Irish situation often was tense in Newark. The 1881 appointment of Winand Wigger, a German American, as bishop of a diocese that then was predominately Irish, and whose clergy were even more predominantly Irish, made tensions even worse.

The German Americans were the second-largest ethnic group in the diocese. Through their national organizations, they appealed to Rome, claiming discrimination. They also demanded their own German-speaking bishops. Rome rejected this demand. The national parish was a logical and pastorally efficient compromise that allowed local ethnic autonomy.

Many Germans had settled firmly in New Jersey by the time of the foundation of the diocese of Newark. Consequently, they were able to absorb the newly arrived German immigrants. By 1900, the number of German Catholics in the diocese had increased to about 24,000 with 13 churches.2 The majority of the German parishes were served by the Sisters of Christian Charity, Daughters of the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Immaculate Conception. This German congregation of teaching sisters first came to the diocese in 1875, staffing the school at Saint Augustine’s German Parish in Newark.

Eventually, the practice of national parishes was adopted widely and used for the newer ethic groups, Italian, Polish, Lithuanian, etc., coming to the United States. However, at no time did all people of a specific ethnic group attend the national church of their language. People always have gone where they wish, even more so today.

Pastoral care of this ever-increasing and ever more diverse flock was daunting. From the establishment of Saint Mary’s Parish (Newark Abbey) for the Germans, the diocese of Newark utilized the model of the personal or national parish for pastoral purposes. This soon became the general practice to address the needs of each new ethnic community.

The most commonly known type of parish, the territorial parish, serves a territory subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the territorial parish. A national parish is a personal parish characterized by the nationality of the parishioners. It is an ecclesiastical jurisdiction that serves a specific community of people but is not necessarily a geographic subdivision.

It is good to remember that these parishes were set up to conduct services in the language of an ethnic group and to promote the group’s traditional religious devotions and customs. The local boundaries of the settlements of ethnic groups of immigrants were not always clear and often overlapped. This led to Italian and/or German parishes amid Irish communities, Slovak parishes in Italian communities, etc. Therefore, today there may be several different national churches within a few blocks of each another.

Although most of the territorial parishes were predominately Irish, and sometimes called the “Irish” parishes, this was not always the case. There was a continual ethnic ebb and flow throughout the years. Often a territorial parish was Irish and German, while there were national German parishes not far away. Examples were Saint Patrick’s in Elizabeth, Saint Aedan’s in Jersey, and Sacred Heart (Vailsburg) in Newark; all of which were predominately Irish but had a significant number of German parishioners.

Italians

The Italians were the next major immigrant group to come to New Jersey in great numbers, beginning in the 1870s. Between 1900 and 1930, 5 million Italians immigrated to America. The European revolutions of the mid-19th century and the struggle for Italian unification destabilized the economy of Italy, particularly southern Italy. The government of newly unified Italy, dominated by northern interests, did little to relieve the plight of the south. It is not surprising that the great majority of Italian immigrants came from southern Italy and Sicily.

Their religiosity was quite different from their Irish and German predecessors. Their exuberant outdoor religious processions and festivals were a source of wonder to the Irish Americans and confusion to the German Americans. Unfortunately, their culture did not lead them to engage as faithfully in church attendance or parish contributions as the Irish and Germans. In Italy, the Church was long established, and it did not depend on the regular offerings of the faithful. Often, they were not welcomed into the now well-established parishes of northern New Jersey. There are many accounts of Masses and other services for Italians restricted to church basements.

National Shrine of Saint Gerard Majella

However, despite these difficulties, priests who were not Italian began much of the pastoral work among the Italians of Newark. The pastor of Saint Bridget’s, Father James Hanley, built the first Italian church in the diocese, Holy Rosary in Jersey City, and Father Conrad M. Schottholder founded the first three Italian churches in Newark.3 The first Italian national parish in Newark was Saint Lucy’s, established in 1891.

Italians also settled in suburbs, leading to the establishment of Italian national parishes in Montclair and Garfield. Many priests serving these new parishioners were from their home countries and either came on their own to the United States or were recruited by the parish or the bishop.

The number of Italians grew at an amazing rate. “Between 1880 and 1920 Newark’s Italian-born population grew from 400 to 27,000. By the latter date another 36,000 were children of Italian parents. Those of Italian birth and parentage made up 15 percent of the city’s population and had become Newark’s largest ethnic group.”4

Polish Immigration and Catholics from the Empires of Europe

While some Polish immigration began earlier, heavy Polish immigration began in the 1870s, and massive immigration in the 1880s and continued until the outbreak of World War I 1914. Since they came from the Polish regions of Germany, Austria, and Russia, it is difficult to determine the exact number of Poles. They regularly were conflated with other nationalities from these empires. It is reasonable to estimate that about 1½ million Poles immigrated during this period. They faced the problems of all immigrants but were better organized ecclesiastically than the Italians and quickly established parish institutions.

The great wave of Polish immigration to New Jersey began in the 1880s.The 1880 census counted only 748 Poles in the entire state. In 1890 the census there were 3,600 Poles in New Jersey, 14,300 in 1890, and 69,000 in 1910. Nearly all of the Poles who came to the United States were from rural areas but settled primarily in cities like Newark and Jersey City. The Poles were generally zealous Catholics who contributed liberally to their churches.

In 1882 the Poles in Newark founded their first fraternal organization, the Jan III Sobieski Society, named for the heroic Polish king. Just seven years later, in 1889, the first Polish parish was founded, Saint Stanislaus. Saint Casimir’s followed not long after, preceded by a fraternal organization, the White Eagle.

The diocese had a difficult time finding Polish-speaking priests. When the first Poles arrived in the early 1880s, only one or two priests in the diocese could hear confessions in that language. At first German-speaking priests staffed Polish parishes, taking advantage of the fact that many Poles from Germany and Austria also spoke German.

The establishment of Polish national parishes came about as “territorial pastors” brought the needs of the Polish immigrants to the attention of the bishop or lay groups petitioned for a parish and a priest. Most were in Newark and Elizabeth and in the urban centers of Hudson County. The first Polish national Parish was Saint Stanislaus in Newark, created in 1889. The school at Saint Stanislaus was staffed by the Congregation of the Sisters of Saint Felix of Cantalice, the Felician Sisters, a Polish congregation that came to Newark in 1895. In Elizabeth, in 1905, the thrust for the establishment of Saint Adalbert’s Polish Parish came from the laity, a movement led by five saloonkeepers and a baker.5

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Catholics arrived in New Jersey from other countries as well. Census records are not always helpful as many came from the Russian, Austrian, and German Empires that contained many nations. In any event, the diocese established national parishes for Slovaks, Lithuanians, and Hungarians, as well as parishes for Eastern Rite Ukrainian Catholics.

Another major group was the Slovaks. The census of 1900 counted 8,404 Hungarians in the diocese, while there had been only 292 in the entire state in 1880. Slovakia was then part of the Kingdom of Hungary and the majority of these were probably Slovaks. Finding accurate statistics is difficult since Slovaks sometimes were listed either as Hungarians, Slavs, Slavic, or Slavonians. The diocese of Newark established one Hungarian and three Slovak parishes. Until priests of these nationalities arrived, priests of other ethnicities served them.

The Lithuanians were another suppressed nationality that began to settle in the diocese about the year 1878. There are no immigration or census figures for them because Lithuania was then part of the Russian Empire. It was very difficult to find a priest who spoke Lithuanian. Saints Peter and Paul Lithuanian Church in Elizabeth was incorporated in 1895.

Catholics of the Eastern Rites also immigrated in the late 19th century. Their celebrated a liturgy quite different from the Latin liturgy and their clergy were married. Married clergy made the predominately Irish hierarchy and presbyterate very nervous. Saints Peter and Paul in Jersey City and Saint Michael in Passaic, parishes of the Eastern Rite, were established without Bishop Wigger’s permission but eventually he regularized their status.6 Eastern Rite Catholics were under the pastoral care of Latin rite ordinaries until the establishment of the first personal diocese for Catholics of the Eastern Rite in 1924.

Sixty Years of immigration

Bishop Wigger, the only Newark ordinary not of Irish heritage, died in 1901. The Catholic population of the diocese of Newark, which then included the three counties of today’s Paterson diocese, had doubled during the 20 years of Wigger’s tenure. In 1882 there were 145,000 Catholics; in 1901, 290,000. The number of priests also had doubled, from 131 to 265. There were 83 churches in 1882; 155 in 1901.7 Of these parishes, 35 were national or language parishes. Thirteen parishes were German, nine Italian, one French and Italian, four Polish (including one in schism), three Slovak, two Eastern Rite, one Lithuanian, and one Hungarian.8

Catholics in the diocese of Newark accounted for about 25 percent of the total population of its seven counties, just over 1.1 million. Since the establishment of the diocese in 1853, the Catholic population of New Jersey had grown from about 30,000 to 362,000. Of this number, the diocese of Newark accounted for 290,000, and the diocese of Trenton, 72,000. Almost all of this growth was the result of immigration.

In the ten-year period from 1890 to 1900, the number of Catholics in the Newark diocese rose from 170,000 to 290,000. In that decade, the new immigration, especially from Italy, made a great impact on the diocese. In 1900, almost 432,000 of New Jersey’s population were foreign-born; in 1910, this swelled to over 658,000, in 1920 to almost 739,000.9

In 1903, the diocese of Newark celebrated its Golden Jubilee. After the Mass, the clergy adjourned to a banquet in the Krueger Auditorium. There they enjoyed a banquet followed by the usual toasts. There was, however, a significant innovation, the toast “to the Immigrants of Today,” offered by Reverend Andrew M. Egan. Father Egan praised the piety, the accomplishments, and the generosity of the immigrants who had established the diocese on a sound footing. He then praised the contemporary immigrants: Germans, Irish, Italian, Poles, and Slavs. He recognized that they did not have the advantage of the Irish in being able to speak English on their arrival in America.

He noted that some had strayed from the faith. However, urging patience with the difficulties of the contemporary immigration, he declared that “the multitude of the immigrants of today will carry on the same work in the cause of God and his holy religion as has been done in the past.”10 Amid the usual triumphal recital of statistics of growth and success, Egan recognized that the diocese had grown but also had changed. It was already, in 1903, a mixture of many nationalities, no longer an Irish and German church.

Seminary enrollment did not reflect this ethnic mixture. Of the 59 students who entered the seminary from 1900 through 1905, 49 were of Irish heritage. The remaining ten included six of German, two of Polish, one of Hungarian, and one of Italian background.11 The diocese made up for this by admitting foreign-born priests, a practice that would continue in the following century. In 1900, there were 20 German-born priests, 20 Italian, and five Polish.12

Significant immigration would continue for a decade or more until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Shortly after the war, restrictive immigration laws, spurred by prejudice, ethnic and religious, chiefly anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish, led to a lessening of immigration for several decades.

Until World War I, immigration was the major source of growth in the Diocese of Newark. In 1900, the foreign-born population of the seven counties was 334,890; by 1910, this had grown to 505,457. Italian immigrants numbered 32,487 in the diocese in 1900. By 1910, just ten years later, Hudson County alone counted almost as many Italians and the total in the Diocese rose to 84,980. The rate of increase of Poles approximated that of the Italians, although they numbered only about one-half of the former’s totals. Other Eastern and southern Europeans migrated in increasing numbers, though none so heavily as the Italians and the Poles. Moreover, the Irish continued to enter in almost unabated numbers, although Germans appeared at somewhat diminished rates. What in the mid-19th century had been essentially a bilingual diocese rapidly became polyglot by the beginning of the 20th century.13

Bishop John J. O’Connor, who succeeded Wigger in 1902, sought to meet the needs of the newcomers through the establishment of parishes and the recruitment of clergy. During his administration (1902-1927), 56 national parishes were established. Of these 26 were Italian, 13 Polish, five Lithuanian, three Slav, three Slovak, two Hungarian, and one each Armenian, German, Spanish/Portuguese, and Syrian. The majority of these had begun to operate before the beginning of World War I in 1914.

The longer established groups frequently did not understand or sympathize with the problems of the newcomers or look upon their varying customs with favor. Indeed, neither the significance of Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations to the Irish nor that of the blessing of Easter bread to the Poles is self-evident to others.

The following graph shows the trends in immigration and the similarities between the first wave and the second wave.

The shift from predominantly Irish and German immigrants in the latter years of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th century is clear from the table below.

Place of Origins, Major immigrant Groups, New Jersey, 1880 and 1920

| Country of Origin | 1880 Number | % | Country of Origin | 1920 Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ireland | 93,079 | 42.0 | Italy | 157,285 | 21.3 | |

| Germany | 64,935 | 29.3 | Germany | 92,382 | 12.5 | |

| Great Britain | 39,803 | 18.0 | Poland | 90,419 | 12.2 | |

| Holland | 4,281 | 1.9 | Russia | 73,527 | 10.0 | |

| France | 3,739 | 1.7 | Ireland | 65,971 | 8.9 | |

| Canada | 3,536 | 1.6 | Great Britain | 65,817 | 8.9 | |

| Other | 12,327 | 5.5 | Hungary | 40,470 | 5.5 | |

| Austria | 36,917 | 5.0 | ||||

| Czechoslovakia | 16,747 | 2.3 | ||||

| Holland | 12,737 | 1.7 | ||||

| Canada | 10,292 | 1.4 | ||||

| France | 10.185 | 1.4 | ||||

| Other | 65,864 | 8.9 | ||||

| TOTAL | 221,700 | TOTAL | 738,613 |

Between 1880 and 1910, the proportion of immigrants in New Jersey’s population rose from 20 percent to 26 percent. Then World War I disrupted immigration and the figure fell back to 23 percent in 1920. However, that was not the whole story. In 1920, another 34 percent of the state’s population were the children of immigrants. Only 38 percent – less than two-fifths – were native-born whites of native-born parents. More than 60 percent were either immigrant or second generation. New Jersey was truly an multi-ethnic state.

As New Jersey became increasingly immigrant, its population became increasingly diverse. The impact of the “new” immigration is evident when we compare the state’s largest immigrant groups in 1880 with those in 1920.

While the British, Irish, and Germans dominated in 1880, they were much less prominent forty years later. Italians constituted by far the largest group and Poles were third. 14

A glance at United States Census Statistics will demonstrate that New Jersey always has been a state with a large immigrant population.

| New Jersey | 1850 | 1900 | 1910 | 1940 | 1950 | 1980 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 489,555 | 1,833,669 | 2,537,167 | 4,160,165 | 4,815,435 | 7,364,823 | 7,730,188 |

| Native born | 429,607 | 1,451,785 | 1,883,669 | 3,460,809 | 4,181,355 | 6,607,001 | 6,763,578 |

| Foreign born | 59,948 | 431,884 | 660,788 | 699,356 | 635,080 | 757,822 | 966,610 |

| % Foreign born | 12.1 | 22.9 | 26.0 | 16.8 | 13.2 | 10.3 | 12.5 |

| New Jersey | 2000 | 2010 | 2016 est. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 8,414,350 | 8,791,894 | 8,944,469 |

| Native born | 7,206,350 | 6,812,738 | 6,928,384 |

| Foreign born | 1,208,000 | 1,979,156 | 2,016,085 |

| % Foreign born | 14.9 | 22.5 | 22.5 |

Our second essay will address the “pause” in immigration from approximately 1920 to 1965.

»II. The “Pause” in Immigration in the Archdiocese of Newark»

Footnotes

- All statistics in this essay are taken from United States Census Bureau Reports.

- Carl D. Hinrichsen. “Winand M. Wigger” in The Bishops of Newark 1853-1978. South Orange NJ 1978, 55.

- Ibid., 59.

- Douglas Shaw. Immigration and Ethnicity in New Jersey History. Trenton, New Jersey Historical Commission. 1994. p. 40

- Ibid., 75.

- Carl D. Hinrichsen. “Winand M. Wigger.” 64-66.

- Beck, Henry G. J. The Centennial History of the Immaculate Conception Seminary – Darlington, N.J., privately printed, 1961. p. 31.

- Carl D. Hinrichsen. “Winand M. Wigger,” 69.

- Wilson, Harold F. et al., Outline History of New Jersey. New Brunswick, NJ, 1950. p. 187.

- Robert J. Wister. Stewards of the Mysteries of God – Immaculate Conception Seminary, 1860-2010, South Orange NJ, 2010, 90.

- Analysis of Registrum Alumnorum et Ordinatorum ex almo Seminario sub titulo Immac. Conc. B. V. M., 76–77, in Archives of Immaculate Conception Seminary (AICS)f B.4.

- Hinrichsen, Carl D. The History of the Diocese of Newark, 1873-1901. Ann Arbor MI, 1987. p. 300.

- Joseph F. Mahoney. “John J. O’Connor, in The Bishops of Newark 1853-1978. South Orange NJ 1978, 70.

- Douglas Shaw. Immigration and Ethnicity in New Jersey History. Trenton, New Jersey Historical Commission. 1994. p. 36-38.