A Personal Note

For more than twenty years, I have served as a weekend assistant at Saint Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral in Newark.

Opened in 1850 in central Newark, Saint Patrick’s has “seen it all.” One Sunday, looking out at the very diverse congregation I decided to do a survey. I asked the congregants to raise their hands as I asked on what continent they were born. For each of the following a hand or several hands rose: North America, Europe, South America, Asia, Pacific Islands, and Africa. I expected that when I said “Australia” that no one would raise their hand, but one hand rose. It was a Rutgers University student from Sydney. Once again, the congregation surprised me! We are all part of a Universal Church and, in Newark; we are a microcosm of the Universal Church.

In 2003, I curated an exhibit in the Gallery of Walsh Library of Seton Hall University that commemorated the 150th anniversary of the establishment of the diocese of Newark. Displaying a wide variety of artifacts, the exhibit highlighted the various immigrant groups that make up the Catholics of the archdiocese. I entitled the exhibit “The People of Newark.” At the same time, I contributed an essay to a special edition of The Catholic Advocate that celebrated the archdiocesan sesquicentennial. It was entitled Welcoming Immigrants, which the archdiocese has been doing since and before its inception. All of us are descended from settlers and from immigrants.

This continuing story still fascinates me. For several years, I have also had the privilege of serving at Saint Andrew Kim Parish in Maplewood. There I experience another aspect of our universal Church.

“So many people misinterpret the universality of the Church. They tried to tell us that to be universal was to be the same.”

Sister Thea Bowman

Franciscan sister of Perpetual Adoration

We now move on to the second great wave of immigration that has created our nation and enriched our Church.

The Second Wave of Immigration

While there clearly was a pause in the intensity of immigration between the passing of the restrictive immigration laws of the 1920s and the immigration reform laws of the mid-1960s, radical changes in the ethnic composition of the archdiocese of Newark already were under way. The Puerto Rican migration and the influx of Cuban refugees were the harbingers of a flood of Hispanic Catholics into the archdiocese over the next half-century. These were not the only forces that would transform the archdiocese. The Second Vatican Council and concurrent social changes in society altered the archdiocese in many ways. We find a useful snapshot of the gradual development of many areas of Catholic life in the annual Directory and Almanac of the Archdiocese of Newark. .

The Archdiocese of Newark 1965

A perusal of the Directory and Almanac of the Archdiocese of Newark for the year 1965 shows a very different institution from today. There are four deans, one for each county, and each one is the highest grade of monsignor – a Protonotary Apostolic. There is a Board of Examiners of Clergy and a Board of Deputies for the Seminary in the areas of Temporalities and Discipline. While Temporalities and Discipline are subject to oversight, there is not even mention of priestly formation.

There is a Catholic Choir Guild and a Commission for Sacred Music. There also were Guilds for Catholic Doctors, Dentists, and Lawyers. Sisters were not forgotten. There was a Commission for Convent Visitation and for Visitation of Religious Communities of Men as well. A Commission for the Vigilance of the Faith and the National Organization for Decent Literature safeguarded doctrine and morals. In another vein, there was the Pope Pius XII Institute of Social Education. Catholic Charities and CYO also were part of the directory.

This glimpse of the archdiocese of 1965 shows us very different emphases when contrasted with the world of today. Some of the organizations obviously are archaic and no longer exist. Many are organs of disciplinary oversight. Others that have been lost are to be lamented, such as the numerous organizations for Catholic professionals in a variety of fields such as law and medicine.

Just five years later, in 1970, the archdiocesan directory added an office for Anti-Poverty Programs, indicating liaison with new government initiatives. The Cursillo Movement has an office and there is a Commission or Ecumenical and Interfaith Affairs, both outgrowths of the Second Vatican Council. Similarly, a Priest Personnel Board has appeared, together with an Office for Retired Priests, a Senate of Priests, and a program for the Continuing Education of Priests. An Office for Inter-racial Justice also is listed, a response to the turmoil of the late 1960s. Quite significantly, by 1970, the Office of the Episcopal Vicar for the Spanish Speaking Apostolate has appeared in the Directory.

The Directory for 1975 mentions an Archdiocesan Pastoral Council. There must have been some controversies at the time because the directory mentions Archdiocesan Boards of Arbitration and of Conciliation. It also lists a Radio and TV Department and an office for the National Blue Army.

A decade later, in 1985, after several re-organizations of the archdiocese, we find a Directorate for Pastoral Services and, within it, a section on Hispanic Concerns with county coordinators for Essex, North Hudson, South Hudson, Union, and Bergen. Not only have the Hispanic migration and immigration made an impact but also within the same directorate there is a section for Multi-Cultural Concerns that includes an Office for Black Catholics and Apostolates for Chinese, Haitian, Italian, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, and Vietnamese Catholics.

By 1990, the directory lists a Filipino Apostolate and we find the Hispanic Apostolate enlarged with several officials, including a Coordinator of Spanish Speaking Deacons.

The directory for 1995 shows another reorganization with a Vicariate for Pastoral Life that included additional offices for a Chaplain to the Indian Catholic Association and a Liaison to the Irish Community.

By the year 2000, there is a Brazilian Apostolate listed in the Directory. Five years later, the Directory takes note of the Nigerian Ibo Catholic Community. The 2010 Directory contains a combined African American, African, and Caribbean Apostolate and the list of ethnic apostolates includes Croatian and Polish/Slavic offices.

Change through the Decades

In 1965, most American Catholics looked to the future with confidence and enthusiasm. The Second Vatican Council closed that year. For a number of years, the archdiocese of Newark had reported a population of about 1.5 million Catholics, about 50 percent of the total population of the four counties that constituted the see. These numbers would decline only slightly over the next half-century but the characteristics of the people of the counties and of the archdiocese would undergo a major transformation.

The number of active diocesan priests serving the archdiocese numbered 847 in 1965. Only half that number were serving in 2015. Over the same period, the number of religious priests dropped from 411 to 131. The number of brothers dropped from 221 to 90. The most dramatic loss was among sisters, going from 3,509 in 1965 to 853 in 2015. For all of these ministers, the average and median age had increased significantly as well. Bright spots were the creation of the permanent diaconate, which gave the archdiocese 168 permanent deacons in 2015, and the growth of lay ecclesial ministers who numbered 545 in 2015.

The number of parishes also declined from 250 to 219 during this period. According to Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, religious practice in the United States also slipped nationally, from 48 percent in 1970 to 23 percent in 2015.

These statistics should not discourage us but simply make us aware of the very difficult pastoral tasks faced by the archdiocese of Newark over the last half-century and continuing today. In these 50 years, the Catholic population moved from an almost exclusively Euro-American majority to an international, multi-cultural, multi-racial, multi-ethnic population that represented every continent in the world. Strangely, not everyone noticed.

No one anticipated this monumental demographic transition. In the mid-1960s, most Catholics focused on the recently ended Second Vatican Council. They devoted their efforts toward the “implementation of the decrees of Vatican II,” and “updating” Catholic liturgy and practice. The novelty of ecumenism and interaction with our Jewish neighbors drew more attention than the gradual changes in many parishes.

No one foresaw the exodus of priests and sisters that began in the late 1960s and continued throughout the 1970s. No one could predict the traumatic effect this would have on pastoral energy and on the financial stability of Catholic institutions, especially schools. Unfortunately, mirroring departures from the priesthood, the number of seminarians dropped from 306 to 111.

The parochial schools had been the mainstay of the evangelization of youth for a century. About half of all Catholic children were in parochial schools in 1965. The 247 Catholic elementary schools in 1965 served 137,129 students, with 81,076 in Confraternity of Christian Doctrine classes. In 2015, the numbers had dropped to 18,079 students in the 66 remaining Catholic elementary schools. While one would think this would occasion an increase in Religious Education classes, in 2015 there were fewer, only 61,837, elementary school students in Religious Education classes. Catholic high schools registered a similar decline from 76 schools with an enrollment of 37,616 to 28 institutions with 13,121 students.

The most striking decline came among women religious. The number of sisters teaching dropped from 2,745 to 75 over this 50-year period. The parochial school, the vehicle that helped immigrant parents pass on the faith to their children, either was not present or had become too expensive for the mostly impoverished immigrant. Clearly new pastoral educational strategies were necessary in this area.

The Hart-Cellar Immigration Reform Law

The Immigration Reform Act of 1965

Something else happened in the years after the close of the Second Vatican Council in 1965. That year President Lyndon Johnson came to Liberty Island to sign the immigration Reform Act of 1965, known as the “Hart-Cellar Immigration Reform Law.” As he signed the law, President Johnson recognized the biases inherent in American immigration policy since the early 20th century as he said that the new law is “one of the most important acts of this Congress and of this administration. For it does repair a very deep and painful flaw in the fabric of American justice. It corrects a cruel and enduring wrong in the conduct of the American Nation.” This law replaced the 1924 immigration act that justified discrimination in immigration based on national origin. That law had severely curtailed immigration from Eastern and Southern European countries and completely prohibited immigration from 39 Asian Countries.

No one really expected what came next. The archdiocese of Newark faced a new and complex pastoral mission that would continue to unfold over the next decades. The urban unrest of the late 1960s intensified the departure of many Catholics from the cities, leaving many parishes in dire financial straits. These relatively poor urban parishes would be at the forefront of the work to welcome and provide pastoral care to the new immigrants from around the world. The archdiocesan financial crisis of the 1970s added to the challenge.

The enormous demographic transformation of the archdiocese that resulted from the new immigration reflected a major shift in the axis of the Catholic Church. A century ago, Catholicism was essentially a European Church. About 70 percent of Catholics lived in Europe and North America, the remainder in the rest of the world. The Church’s almost two-thousand-year-old culture was essentially European. Events of the second half of the 20th century would shift this axis so that, in the 21st century, only about 30 percent of Catholics lived in Europe and North America, where the faith was in decline. The great majority of Catholics, about 70 percent, lived in the “global south.” They lived in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. By the end of the 20th century, Africa was the area of greatest and most rapid growth in the faith.

The immigration to the archdiocese of Newark reflected this radical change. The new immigrants came from the global south, from Latin America, Asia and the Pacific Islands, and from Africa. It is not surprising that many characteristics of this immigration are quite different from the immigration of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and will require different pastoral responses.

Father Simon C. Kim, a Korean-American theologian, summarizes this phenomenon.

This immigration also took place under the umbrella of the Second Vatican Council and the many changes it introduced into the Church. We can use terms such as pre- and post- Vatican II immigration to describe this phenomenon. “If we do not do so – if we do not articulate these specific moments of immigrant history, which is also synonymous with salvation history – then we misunderstand the working of Vatican II and the cultural consciousness raised by the conciliar event. The trouble with the church in the United States is that we do not appreciate how immigration has affected it, created the foundation for it, and continues to fuel the growth of the church for generations to come…The U.S. church often speaks of immigration from its European immigration experience, which reveals the importance of the US ecclesial experience. Within this experience, however, is a complex system of how Catholics from European descent had segregated themselves into national parishes and later generations had merged into a uniform English-speaking community.

This development of the local church from segregated national churches into a uniform parochial entity is a powerful image in the minds of today’s church leaders — a foundational image of how the church began but not necessarily of how the church should always move forward. In speaking of a pre-Vatican II immigration, the church is able to preserve and honor the Euro-American Catholic experience and continue to build on it. This remembrance, however, is not always one that is replicable, since the context of immigration is vastly different today. For instance, racial and biological similarities allowed for a unified parochial system once the linguistic barriers no longer existed. The similarity of Europeans in creating a Euro-American Catholic experience was a great advantage in the pre-Vatican II immigration experience.

Where the pre-Vatican II immigration experience created a unified Euro-American Catholic expression, the post-Vatican II immigration experience is creating diverse Catholic expressions that share but continue to develop from the richness of their homeland in addition to the faith found in the United States. Gleaning important lessons from both situations continues to enhance the local churches of the United States beyond just population numbers. The error occurs in expecting the same outcome of a pre-Vatican II immigration experience. …The past can only provide lessons or guideposts as we move forward into the emergence of the local church.

Just as we cannot return to a pre-Vatican Ii world, we cannot continue to meet the needs of those who arrive on our shores within a pre-Vatican II immigration model.1

We will begin with the most obvious phenomenon of the last six or seven decades, the spectacular growth of Hispanic Catholicism in the United States. We will examine it is all of its own special diversity. While we concentrate our own four counties that constitute the Archdiocese of Newark, Hispanic Catholicism is an international reality that stretches from far north of the Rio Grande to Tierra del Fuego, and a national reality from Miami to Maine, from California to Connecticut, not to forget Spain itself.

In numbers, the next largest groups of Catholics came to New Jersey from Asia and the Pacific Islands, the greatest number from Korea and the Philippines, and other important groups from Viet Nam, China, and India, cultures as vastly different among themselves as from that of Europe and North America.

Centuries ago, Africans were brought to North America as slaves; today they come as immigrants. Many, very highly educated, come to the Archdiocese form Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Kenya, and other African nations.

Lastly, we return to the immigration of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Catholics of southern and eastern Europe never completely stopped migrating to the United States and to the Archdiocese. Among the largest numbers of “new” European migrants, we find folks from Poland and Italy, as well as from Ireland.

It may be giving away the story, but what do we find in the Archdiocese of Newark today? We find that the 2019 Directory of the Archdiocese lists 82 parishes as part of the Hispanic Apostolate. The Archdiocesan Office of Research and Planning informs us that these parishes are all across the archdiocese. A total of 84 parishes offer Mass in Spanish, another eight offer bilingual Spanish and English Masses, and one parish offers a bi-lingual Spanish and Portuguese Mass.

Hispanic Apostolate – Archdiocese of Newark – 2019

| County | Parishes | Priests | Deacons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bergen | 21 | 26 | 2 |

| Essex | 25 | 41 | 11 |

| Hudson | 24 | 38 | 11 |

| Union | 12 | 17 | 3 |

| Total | 82 | 122 | 27 |

What about our other ethnic and language groups?

| Language | Parishes |

|---|---|

| American Sign Language | 1 |

| Bi-lingual English – Italian | 3 |

| Bi-lingual English – Korean | 1 |

| Bi-lingual English – Polish | 2 |

| Bi-lingual English – Spanish | 9 |

| Bi-lingual English – Swahili | 1 |

| Bi-lingual Spanish – Portuguese | 1 |

| Chinese | 1 |

| Creole (Haitian) | 6 |

| Croatian | 1 |

| Filipino (Tagalog) | 13 |

| Igbo (Nigeria) | 1 |

| Italian | 13 |

| Keralan (India) | 1 |

| Korean | 5 |

| Latin (Tridentine Rite) | 2 |

| Lithuanian | 2 |

| Polish | 16 |

| Portuguese | 14 |

| Slovak | 1 |

| Spanish | 84 |

| Vietnamese | 2 |

Here is another way to look at where we are today. This chart shows us the percentage of the population of our four counties by the ancestry (not necessarily the birthplace) of various ethnic/national groups. This is NOT the percentage of Catholics but the ethnic/national group. However, these groups are significantly Catholic.

| Ancestry and/or birth Percentage of population |

Bergen | Essex | Hudson | Union |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irish | 12.03 | 5.98 | 6.33 | 8.25 |

| Polish | 5.27 | 2.42 | 3.18 | 4.87 |

| Italian | 17.56 | 9.47 | 7.62 | 10.28 |

| German | 8.10 | 3.08 | 3.62 | 6.04 |

| Portuguese | 0.46 | 1.64 | 1.06 | 3.20 |

| West Indian | 1.40 | 9.19 | 1.56 | 3.86 |

| Dominican | 3.56 | 3.16 | 7.71 | 3.23 |

| Puerto Rican | 3.58 | 7.24 | 8.67 | 5.26 |

| South American | 5.60 | 5.98 | 11.50 | 9.21 |

| Mexican | 1.18 | 1.15 | 3.29 | 2.11 |

| Central American | 2.01 | 2.50 | 6.52 | 6.17 |

| Filipino | 2.29 | 1.17 | 3.38 | 1.46 |

| Korean | 6.14 | 0.36 | 0.75 | 0.25 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 0.51 | 3.21 | 1.06 | 1.15 |

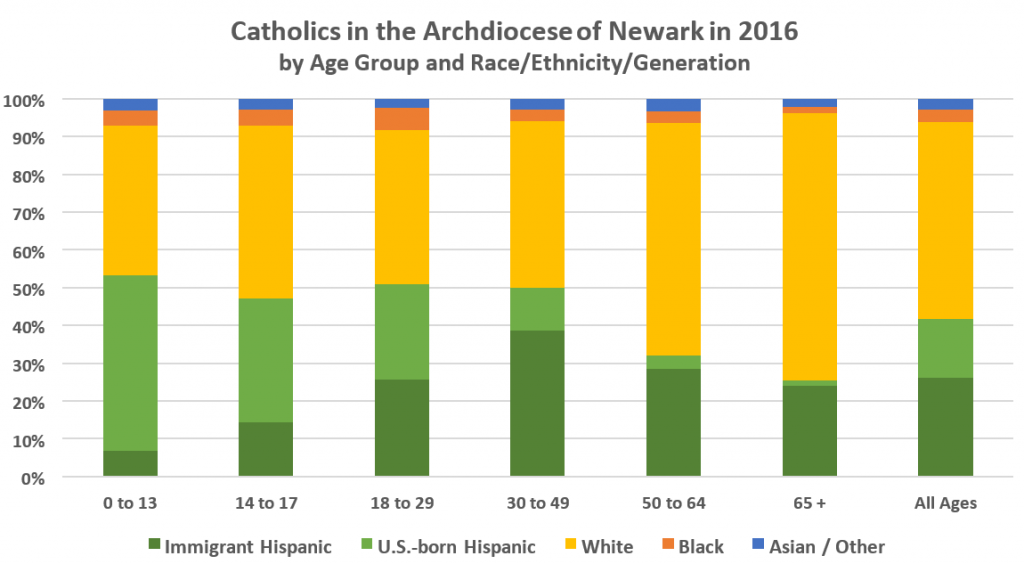

The V Encuentro in 2019 has provided a wealth of information on the Hispanic population throughout the United States and within each diocese. The following information comes from the statistical studies done for the V Encuentro. These statistics may not be exactly the same as in this study. However, the trends are the same.

Key Demographic, Social, and Religious Statistics for the Archdiocese of Newark

<td “>558,858

| Racial/Ethnic Groups in the Archdiocese of Newark | Total Population in 2000 | Total Population in 2016 | % Change | Estimated Catholics in 2016 | % Catholic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 1,436,222 | 1,193,025 | -17% | 528,000 | 44% |

| Hispanic | 829,047 | 48% | 423,000 | 51% | |

| Black | 564,583 | 566,873 | 0% | 34,000 | 6% |

| Asian/Other | 249,604 | 378,633 | 52% | 29,000 | 8% |

| Total | 2,809,267 | 2,967,578 | 6% | 1,015,000 | 34% |

- Number of parishes with an organized Hispanic Ministry: 82

- Total regular Mass attendance in Spanish:

- 43,755 at 142 weekly Masses in Spanish in the Diocese

- 216 at 2 monthly Masses in Spanish in the Diocese

- Number of Hispanics/Latinos enrolled in Catholic schools:

- Kinder to 8th: 3,898 out of 17,775 enrolled</liL

- High School: 2,151 out of 12,628 enrolled

- Number of Hispanic/Latino priests in the Diocese…

- Active: 80

- Retired/Inactive: 9

- Foreign-born: 71

- Number of Hispanic/Latino/a religious living and/or serving in the Diocese: 18

- Number of Hispanic/Latino deacons living and/or serving in the Diocese: 30

More information may be found at the V Encuentro website.2 vencuentro.org

As we move to the next chapter, we recount the journeys of hundreds of thousands of our brothers and sisters.

«II. The “Pause” in Immigration in the Archdiocese of Newark« : »IV. The Second Wave and The Great Hispanic Migration and Immigration Part One»