Cornwall

Background on the Location:

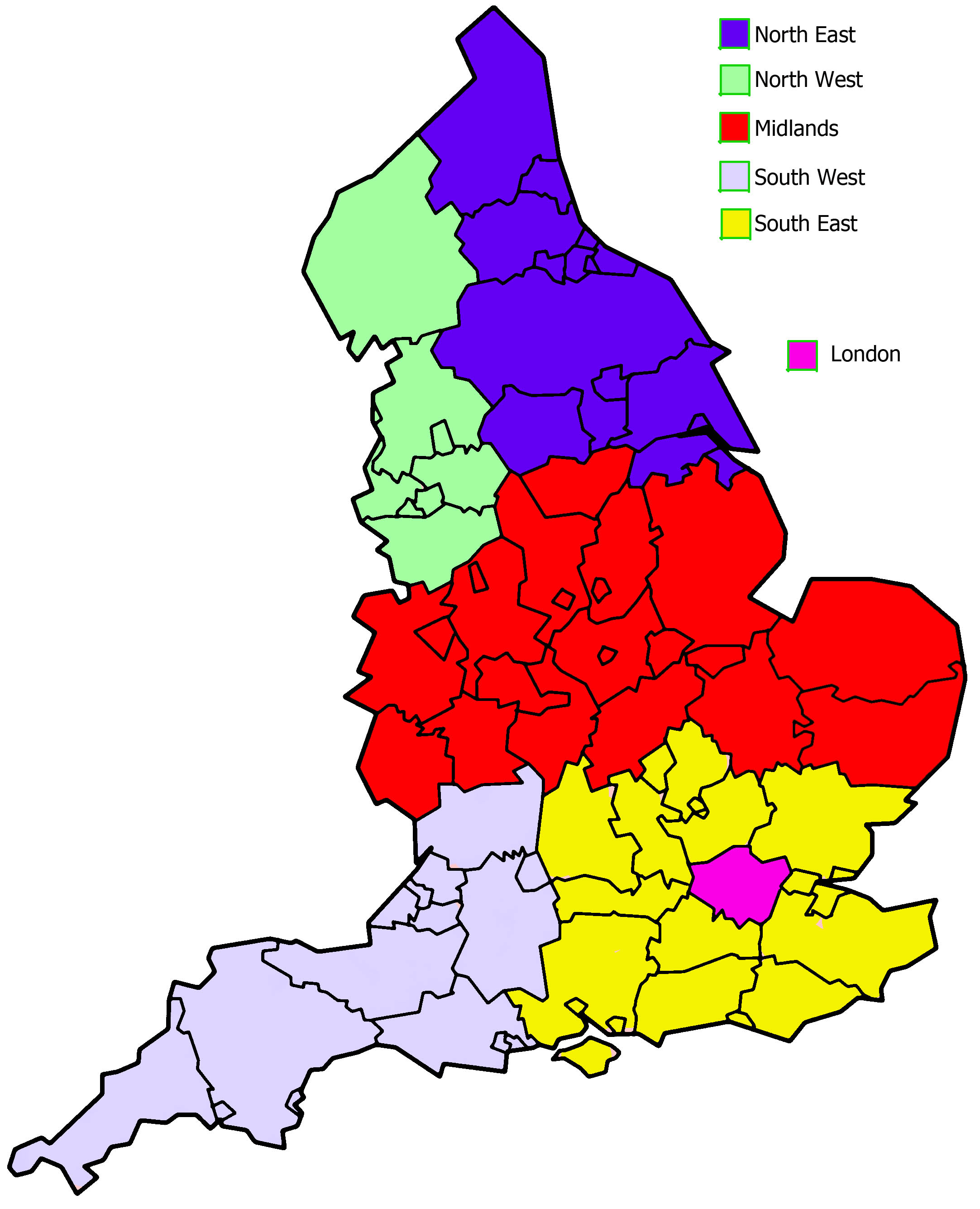

In the United Kingdom, there is a country called Cornwall in the South West part of England. This country is surrounded by the Celtic Sea and the English Channel. Zennor is a village in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom.

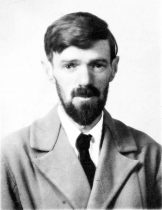

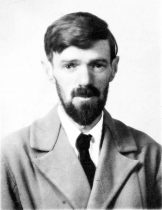

Between the years of 1915 and 1917 D.H. Lawrence and his wife Frieda lived near Zennor. During this time he finished his book Women in Love. The Lawrences were accused of being German spies off the Cornish coast. D.H. and Frieda “were harassed constantly by the authorities and they were eventually asked to leave Cornwall”. The Defense of the Realm Act (DORA) “gave the couple a three-day notice to leave their home”. Lawrence later describes “his and his wife’s experiences with DORA in his novel Kangaroo”.

Effect on the Arts:

The “scenery and strong light” upon Cornwall had great influence on visual art. “Writers, sculptors, and painters were some artists that were influenced by the beauty of Cornwall”.

“Modernist writers such as Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, and Katherine Mansfield lived in Cornwall between the wars”. Several books and other forms of artwork were documented within Cornwall.

Wikipedia pages for Zennor and Cornwall:

“Zennor.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Oct. 2017. Web. 20, November. 2017.

“Cornwall.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 19 Nov. 2017. Web. 20, November. 2017.

The Village Of Zennor/Cornwall:

“It lies above the high, rocky cliffs of the coast and the rugged, boulder-strewn, granite hills and moors” (Cornwall Guide). During the First World War, the Lawrences stayed in Tinner’s Arms, following Higher Tregerthen which is near Zennor. The locals of “Zennor were very suspicious of the Lawrences’ presence within their village”. Although Frieda was German, the Lawrences had no connection to being spies for her country. “The local police lead an investigation and with their findings, the Lawrences were asked to leave”. This suspicion of the people could be looked upon as far due to D.H. being very vocal with his opinion about the people of Cornwall.

“When he first went to Cornwall, he was very critical of the Cornish describing them as …like insects gone cold, living only for money, for dirt. They are foul in this. They ought all to die. Yet in the next line, he admits …Not that I’ve seen much of them – I’ve been laid up in bed. But going out, in the motor and so on, one sees them and feels them and knows what they are like. It’s hardly surprising that the locals didn’t care for the eccentric writer” (Lawrence, Cornwall Guide).

Cornwall Guide of Zennor:

“Zennor.” Cornwall Guide, 18 Sept. 2016. Web. 20, November. 2017.

Zennor, Cornwall: Where Writer DH Lawrence was accused of Spying

In 1915 an English writer arrives at Cornwall. According to the people of Cornwall this writer, D.H. Lawrence, was quite controversial.

“Lawrence absolutely loathed the war and would speak out very aggressively against it without very much sensitivity to other people’s beliefs and feelings and he upset a lot of the locals; there is this strange artist turned up with his German wife telling us that the war is bad that’s not necessarily going to go down very well. And there were fears that not only was Lawrence decrying the war effort but he was aiding the enemy” (Professor Tim Kendall).

Lawrence was “accused of signaling German boats off the north coast of Cornwall”. The couple was supposedly “sending coded messages by the particular ways they hung up their laundry on their wash line”.

“As the war progressed, anti-German feeling in the country grew, and some of the Cornish people turned against Lawrence and Frieda. War-time rumors developed: there was a stock of petrol for German submarines at the bottom of the cliffs near the Lawrences’ cottage: the patterns on the Lawrence’s chimney were a signal for patrolling submarines (the main Atlantic convoy route lay along the nearby coast). They were stopped on one occasion by a military patrol and their shopping searched (a square loaf of bread was seized on as a camera)” (Cornwall Calling).

The “paranoia and fear amongst the people and authorities of the war was very thorough”. The main rulings for accused spies were under the jurisdiction of DORA. “These rulings were created to constant outbreak after the war”.

“The Government making legislation in wartime that gives them incredible powers to intervene in civil life. It was first passed on the 8th August 1914 but there were six or seven variations of it over the course of the war” (Dr. Catriona Pennell, University of Exeter).

WW1 at Home BBC: Zennor, Cornwall

Kendall, Tim, and Catriona Pennell. “World War One At Home, Zennor, Cornwall: Where Writer DH Lawrence was Accused of Spying.” BBC, BBC, 28 May 2014. Web. 20, November. 2017.

“World War One At Home – BBC Radio Cornwall.” BBC, BBC, 2014. Web. 20, November. 2017.

Timeline with D.H. Lawrence’s Works:

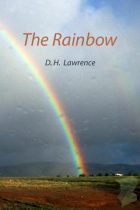

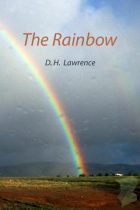

In 1915, “D.H. wrote The Rainbow and was prosecuted by the Public Morality Council for obscenity.” Bow Street ordered over a thousand copies to be destroyed. This “uprising destroyed Lawrence’s source of income and any further chances of being published again in England”.

Works that Feature Cornwall after his departure:

1918- The Fox

1923- Kangaroo

D.H. and Frieda were married shortly after her divorce on July 13, 1914 in the Kensington’s Registrar’s Office. The “couple’s original plans were to return to Italy after their wedding but due to the outbreak of war they had to remain in England”. This is when the Lawrence’s purchased the Tregerthen Cottage in Zennor.

“They found a cottage in Zennor that they could rent for five pounds per year. They bought some second-hand furniture and moved in during March 1916. They persuaded Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murray to take the cottage next door. However, Katherine hated it there and Murray turned down Lawrence’s offer of blood-brotherhood and after only a few weeks they left” (Cornwall Calling).

“D.H. Lawrence, author.” D.H. Lawrence, author. Web. 20, November. 2017.

The Letters and Quotes

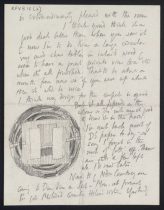

‘“A letter written by Frieda in February 1917 refers to 3 ships being torpedoed “just here” and they saw the men struggling in the water. In 1917 they were accused of signaling to submarine crews in the channel using lights, and their cottage was searched by the police. Finally, on October 11th, 1917 they received an order to leave the county by the 15th, under the Defense of the Realm Act”’ (Cornwall Calling).

“When we came over the shoulder of the wild hill, above the sea, to Zennor, I felt we were coming into the Promised Land. I know there will be a new heaven and a new earth take place now: we have triumphed. I feel like a Columbus who can see a shadowy America before him: only this isn’t merely territory, it is a new continent of the soul” (Moore 437).

Letter of 25 Feb. 1916 to Ottoline Morrell, from The Collected Letters of D.H. Lawrence, ed. Harry T. Moore (Heinemann, London: 1962, repr. 1970), vol. 1, p. 437. 20, November. 2017.

[Jan. 1916, Porthcothan, to J.D. Beresford]: “We have been here a week…We love being here. There have been great winds, and the sea has been smoking white above the cliffs – such a wind that it made one laugh with astonishment…I do like Cornwall. It is still something like King Arthur and Tristan. It has never taken the Anglo-Saxon civilization, the Anglo-Saxon sort of Christianity. One can feel free here, for that reason – feel the world as it was in that flicker of pre-Christian Celtic civilization when humanity was really young – like the Mabinogion – not like Beowulf and the ridiculous Malory, with his grails and his chivalries. But the war has come” (Lavery).

[7 Jan. 1916, Porthcothan, to Katherine Mansfield]:”…I love being here in Cornwall – so peaceful, so far off from the world…a fine thin air which nobody and nothing pollutes. [But he’d been very ill with the respiratory disease later diagnosed as TB, as well as suffering a deep spiritual depression that he struggled to vanquish in his admiration of the Celtic otherness of Cornwall, ‘bare and dark and elemental’, as he described it in another letter, to Catherine Carswell]” (Lavery).

[17 Jan. 1916, Porthcothan, to J. Middleton Murray and K. Mansfield]: “I still like Cornwall…The landscape is bare, yellow-green and brown, dropping always down to black rocks [this sounds to me like Chaucer, The Franklin’s Tale, with its ‘rokkes blake’ of Brittany, which topographically resembles those of W. Cornwall] and a torn sea. All is desolate and forsaken, not linked up. But I like it” (Lavery).

[24 Feb. 1916, Porthcothan, to JM Murray and K. Mansfield] “We went out looking for a house, and I think we have found one that is good. It is about 7 miles from St Ives, towards Land’s End, very lonely, in the rocks on the sea, Zennor the nearest village: high pale hills, all moor-like and beautiful, behind, very wild: 7 miles across the country to Penzance. [They stayed briefly at the village pub there, The Tinner’s Arms – it’s still there, next to the church dedicated – a rare instance of this – to St Senara, with its pew-end carved famously in the form of the Mermaid of Zennor. He goes on:] Primroses and violets are out, and the gorse is lovely. At Zennor, one sees infinite Atlantic, all peacock-mingled colors, and the gorse is sunshine itself, already. But this cold wind is deadly. [His health was precarious, and this climate would not be good for him, as he soon found. But he clearly longed for this move to work]” (Lavery).

Lavery, Simon. “DH Lawrence in Cornwall, pt 1 – The Promised Land.” Tredynas Days, 8 Jan. 2017. Web. 20, November. 2017.

“’It is a most beautiful place,’ he rhapsodized to friends. ‘A tiny granite village nestling under high, shaggy moor-hills, and a big sweep of the lovely sea beyond”’ (Lawrence, Aslet).

Zennor, Cornwall Today

“WHAT TO SEE: The Wayside Folk Museum at Zennor is housed in a listed watermill, but before you dash in, linger outside to see its plague stone: vinegar was put into a hollow in order to disinfect coins so that they could be exchanged with neighboring parishes in times of cholera.

WHERE TO EAT: The Tinner’s Arms is everything a country pub should be – log fires, stone floors, good local food. It was built in 1271 to house the masons who constructed St Senara’s church.

WHERE TO SHOP: You can’t buy much in Zennor, so head for the Trelowarren Gallery, near Helston, which has a wonderful display of Cornish craftwork.

WHERE TO STAY: Next to the Tinner’s Arms, the White House, built in 1838, offers bed and breakfast”

Aslet, Clive. “Zennor, Cornwall, buried treasure in D.H. Lawrence country.” Daily Mail Online, Associated Newspapers, 19 Mar. 2010. Web. 21, November. 2017.

When Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant first got the house, the garden was used for fruit and vegetable plants and trees.

When Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant first got the house, the garden was used for fruit and vegetable plants and trees.  Following the First World War, Roger Fry designed a new layout for the garden so it could include more flowers and pool. The garden was to be shaped like a rectangle. As time passed, the garden slowly began to take shape. Quentin Bell contributed to the garden with mosaic pavements and pools.

Following the First World War, Roger Fry designed a new layout for the garden so it could include more flowers and pool. The garden was to be shaped like a rectangle. As time passed, the garden slowly began to take shape. Quentin Bell contributed to the garden with mosaic pavements and pools.