Focus on Child Soldiers: Burma

By Anthony Tokarz

Staff Writer

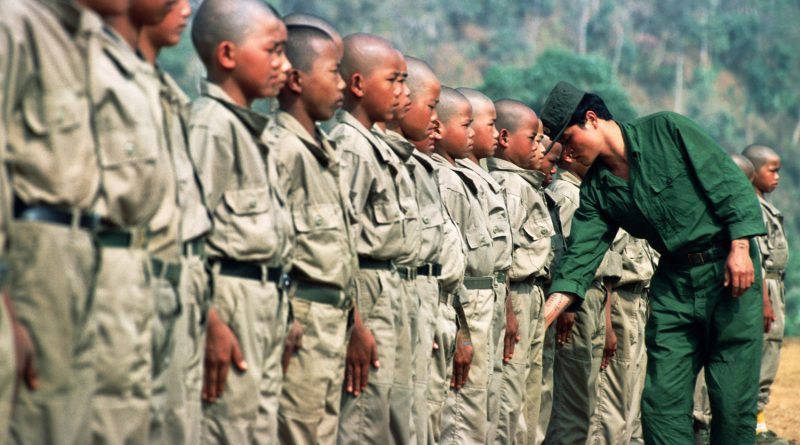

From 1989 to 2002, while the United Nations was condemning the forced recruitment of child soldiers through the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention, and the Rome Statute, Burma doubled the size of its military to about 350,000 active soldiers, of which child soldiers under the age of 15 constitute an estimated 20 percent, according to Human Rights Watch.

Army agents approach children as young as 11 in public spaces, such as markets, and demand they enlist in the military on pain of imprisonment. CNN reports that recruiters often promise poor children employment to lure them away from their homes. Recruiters then abduct these children and take them to military training camps, deny them any opportunity to contact their families, and beat to death any who attempt to run away.

The Burmese military has operated counter-insurgency operations non-stop since its establishment in 1948, and has many powerful rivals for territorial control. The United Wa State Army, Burma’s largest opposition group, employs child soldiers sourced from its autonomous region in the east of the country. The Kachin Independence Army also conscripts child soldiers, and is the only army in Burma to conscript girls as well. Until the 2012 signing of an intra-group agreement, reports Irin News, Karenni Army and Mon National Liberation Army likewise depended on child soldiers to continue their violent insurgency campaigns against the national government.

These latter armies have by and large kept to the agreement as peace returned little by little to their respective regions. However, Human Rights Watch concludes that Burma, which promised to enact a similar policy in its Joint Action Plan with the United Nations, has not kept pace, having “failed to meet even the most basic indicators of progress.” However, CNN found that the government has freed a small number of soldiers—68 in 2013 and 404 since then—in order to stage elaborate ceremonies attended by military and government officials to bolster its image both at home and abroad. Indeed, the Guardian insists that these releases do not affect the systematic recruitment of children from poor families across the country.

To make matters worse, criminals and other paramilitary organizations recognize the Burmese government’s need for child soldiers, and stepped in as brokers to meet demand. The Pulitzer Center highlighted how these civilian brokers sweep cities late at night in search of boys, whom they then intimidate into compliance. The army pays these brokers $80 per conscript, or barters bags of rice or oil. Soldiers within the army do not receive leave from their duties unless they can procure one or two conscripts to take their place. Any observer can recognize this phenomenon for the blatant human trafficking it is.

Thus, the practice of trafficking child soldiers has two primary causes, political and economical. Insurgencies carried out by regional separatists fuel demand for army personnel, and the poverty of the Burmese population induces civilians to sell children to the military for the equivalent of several months’ wages. Despite the prominence of this issue throughout international law institutions, non-governmental organizations, and the United Nations system, Burma does not have the capacity, nor perhaps even the desire, to end the practice until it has satisfied its desire for authority in contested territories. On the supply side, traffickers in child soldiers will not desist until they receive viable alternatives for earning a livelihood.

This is a cross-cutting issue, but in examining its causes, economics looms as large as politics. The Burmese government has already proven capable of providing financial incentives to its citizens, if only for the purpose of fueling its child soldier recruitment. It might find this practice unnecessary if it can prove to the separatist insurgents on its hands that it can provide a better life than their demagogic leaders, and steal their loyalty. Economics seems the best instrument for this, though the government must itself identify the appropriate form.