Throughout the expansion and growth of New York, it was never a secret that the upper- and middle-class individuals residing in the city were catered to more than those below a certain status. In more than a handful of instances, class played a very big part – and still does in many cases – in determining what spaces were available to who, the decorating and building of locations and buildings, and the expansion northward from the original point of New York City. At the turn of the century, public leisure was becoming more popular as spaces began arising that individuals could go to spend money and engage in culture otherwise not available before. The most common place for the wealthy and high society to gather was in hotels. It was common for individuals to gather on roof tops, such as the famous Hotel Astor garden roof top, and look down over the city – both literally and figuratively. However, all great and famous hotels must have their start in history, and some hotels do not begin originally as being a hotel at all.

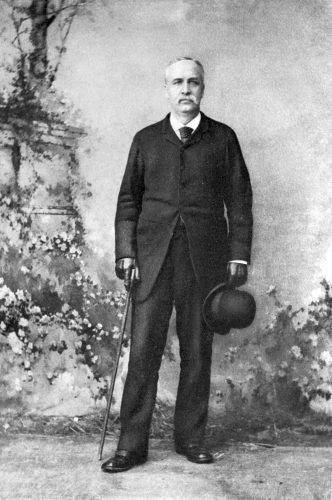

Henry Villard was a railroad tycoon and savvy businessman. Born in 1835 in Speyer, Rhenish Bavaria, Villard was educated from a young age and quickly went on to study at universities in Munich and Würzburg before emigrating to America. He arrived in New York in 1853 where he wasted no time in building his empire in all spots around the country. Villard moved from New York to Chicago to California and Oregon… and everywhere he went, he made his mark with lasting connections. He was a correspondent for a number of newspapers, including but not limited to the New York Tribune and the New York Herald. He also held control over major transportation lines Northern Pacific, Oregon & Transcontinental, and the Oregon & California Railroad. He also “organized the Oregon Improvement Company for the development of the natural resources,” resulting in his domination of “every important agency of the transportation” in the west. Despite his railroad career ending in 1893 after a number of mishaps, Villard was still exercising his versatility when he realized the “possibilities of the electrical industry” and he lent financial aid to Thomas Edison and founded the Edison General Electric Company in 1889[1].

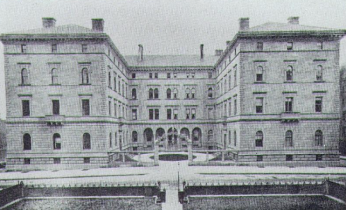

As a strong businessman, Villard decided he wanted to live like the elites around him did, and he ordered the construction of six brownstone mansions for himself and close friends to reside in. A newspaper from 1880 discussing what are now known as the Villard Houses wrote that Henry “rewarded himself [with these brownstones] for ‘conquering the west’”[2]. He requested the firm of McKim, Mead and White to build the Italian renaissance inspired mansions on the property behind St. Patrick’s Cathedral at 455 Madison Ave, New York, NY, which he bought from the Catholic Archdiocese of New York[3]. The Villard Houses were “of a classical Roman palazzo style that found favor among the new American millionaires as expressive of great wealth, aristocratic position relative to the middle class, and triumph in the economic and social Darwinism of the day.” While these were individual brownstones being built, it was designed to appear as one large mansion, so the buildings were connected. The commission to design and build this property gave the firm of McKim, Mead, and White the mobility and recognition to become known as “preeminent architects in service to the Gilded Age,” and led to the fast-paced launch of their careers in New York City”[4]. Despite what the Villard Houses were being built to look like from the outside, the inside was not as glamourous as it is today. The famous Gold Room in which Villard was believed to have spent his glory days in was in fact not even gold at the time he resided in the residence. When he lived there, the Houses were still under construction, however, he was forced to leave his residence after an angry group of individuals gathered outside, demanding money back that Villard had coaxed his friends into blindly investing insomething. He had instead used the money to buy the Northern Pacific Railroad. In 1886, the Villard Houses were sold to Whitelaw Reid, who was the owner of the New York Herald and Tribune, who began to transform the rooms to what Villard had only dreamed of[5].

Under the ownership of the Reids, Standford White was called back to the property to design the Gold Room with nothing but the finest materials – something only Villard had dreamed of doing but never actually accomplished. White transformed the Gold Room into a glorious study “with a ceiling bookishly adorned with the colophons of publishers,” and the room held one of the most outstanding events on property: The Grand Ball for Edward, Prince of Wales, in November of 1919[6].

Although going through very few owners, the Villard Houses were not transformed more than once. Along with the Reids family, the mansions also served as a Woman’s Service Club during the war. The Gold Room also became a “consultary for the Cardinal” when the property was bought back by the Archdiocese in 1948[7]. The northern wing of the mansions also served as offices for the publisher Bennet Cerf and Random House. Cerf, who loved the property, promised to have to be carried out should the day come that he must leave, and he stood by that promise when Random House finally outgrew the space[8].

The Archdiocese outgrew its offices in the Villard Houses in 1970s, and put the property up for lease after designating the outside of the buildings as a city landmark. They purchased the remainder of the property back from Random House after a very generous donation of $2.25 million allowed them to do so[9]. The donation had been made by the former chairman of the Gillette Safety Razor Company, Henry Gaisman. A New York Times article dated March 12, 1971, discusses the fact that the Archdiocese now purchased the Villard Houses which had been designated a landmark in 1968. They purchased the property out of fear “that acquisition of the property by a single owner might lead to demolition to make way for an office building”[10]. The article included the paraphrasing of a statement made by the chairman of the commission, Harmon Goldstone, who stated that he “thought the archdiocese would be willing to discuss ways of permanently preserving the structures, perhaps by selling the air rights over them to adjacent property owners who could then build higher than they can now”[11].

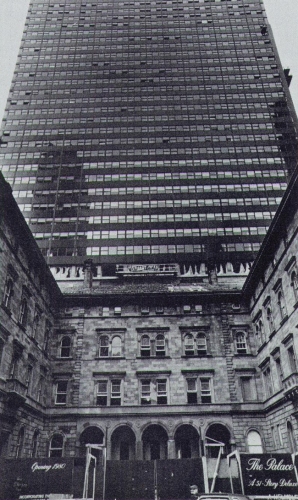

This statement seemed to ring true as a New York Times newspaper article dated December 1974 titled “Villard Houses: Option for the Future” introduces Harry Helmsley, the real-estate developer and hotelier who would transform the property to what is now the famous Palace Hotel. While the Villard Houses were (and still are) protected by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, Helmsley proposed a plan of building a hotel and office tower behind the Houses, using the original grouping as the entrance to the hotel[12]. However, as the proposal for what would be built on the property was given, many did not seem as awed by what would seemingly be placed behind the Villard Houses, and the general feedback from the public was that the proposed hotel would not breathe life back into the brownstones. Individuals thought the hotel did not fit with the design of the façade of the brownstones, and that it was going to be more flash than it was cohesive and actually pretty[13]. Helmsley did eventually begin to lease the Villard Houses, the land they were built on, and the 200-foot by 200-foot property behind them that the Palace Hotel now stands on, for around a million a year for 99 years[14]. While he originally wanted to gut the Villard Houses for his hotel, Helmsley was convinced by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Municipal Arts Society to do a careful renovation and restoration process, instead. This cost Helmsley $10 million; however, the outcome was beautiful and earned him a title in newspapers as developer-restorer[15].

When renamed to the Helmsley Palace, the hotel exuberated extravagance to the highest degree. It was described in 1980 as a “glassy eminence of 1,100 rooms, some of them elegant duplex and triplex apartments, [soaring] above Henry’s house”[16]. Designed by the architects Emery Roth and Sons, the tower rose behind the Villard Houses, with “piers sheathed in travertine” to bring “instant class ever since Lincoln Center”[17]. The tower was also topped by arches to resemble many other Helmsley-Roth collaborations that had been completed before. Visitors on opening day came to visit not only the hotel itself, but the treasures that had been put inside of it for decoration.

A quote from a guest visiting on opening day, September 16, 1980, is documented in a New York Times article: “Where’s the clock? You know, the one designed by Augustus St. Gaudens and Stanford White”[18]. The elegance of the building in comparison to the Villard Houses was striking, and Helmsley was proud of his work when he opened his doors to the royalty and top figures in both politics and entertainment to come visit the Helmsley Palace Hotel for the first time. To run his hotel, Leona Helmsley, Harry’s wife, was put in charge. She became infamous for her harsh working style and environment, which instantly earned her the nickname “Queen of Mean.” A display ad for the hotel from May 1983 shows an image of Leona Helmsley in the lobby of the Palace. The caption reads: “It’s the only Palace in the world where the Queen stands guard”[19]. The description beneath reads: “Peruvian lilies, freesia, and tulips – that’s the order of the day. And Leona Helmsley, proprietress of the Helmsley Palace Hotel, sees that each petal is in place throughout exquisite 100-year-old lounges. What better way to please her royal family. You. Her guests”[20].

The world the Helmsley Palace created was one of extreme extravagance for most elite and upper-class individuals in the city. Much like hotels had become at the turn of the century, the Palace Hotel was transformed into this space where only the most influential and affluent were given access. It was marketed as “the most magnificent hotel to open in New York in a century”[21]. However, the history of the Palace Hotel after the Helmsley’s becomes lost in translation. Through their own website, it is known that the Sultan of Brunei purchased the property in 1992 where it “underwent a multi-million-dollar restoration and refurbishment,” and it was sold again in 2011 to Northwood Investors. In 2015, Lotte Hotels and Resorts, a company from Seoul, South Korea, received the hotel from Northwood Investors for $805 million, and the property was renamed to the Lotte New York Palace Hotel, as it is now formally known[22]. The atmosphere of the hotel has not changed through the centuries. A most recent wedding announcement from the New York Times discusses the wedding of two very influential individuals, one of whom is a direct descendent of Plymouth Rock governor William Bradford[23].

The Villard Houses were created as an elitist property for arguably one of the most influential and powerful men in the United States at the time, Henry Villard, and it was transformed into an affluent and female-ruled bubble by Harry and Leona Helmsley. Today, the atmosphere is still very much the same, where individuals from all around the world can escape the busy streets of Madison Avenue and 50thAve in a secluded and quiet lobby, with rooms that look down on St. Patrick’s Cathedral – only if they can afford to, that is.

Notes:

[1]“Henry Villard.” In Dictionary of American Biography. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1936. Gale

In Context: Biography. Accessed 29 Mar. 2020.

[2]Peter Dragadze. “The House that Henry Built and Harry Topped,” Town & Country, 1980, 142-142, 144.

[3]Ibid., 2

[4]Craven, Wayne. Stanford White: Decorator in Opulence and Dealer in Antiquities. NEW YORK: Columbia

University Press, 2005. 16-17.

[5]Peter Dragadze. “The House that Henry Built and Harry Topped,” Town & Country, 1980, 142-142, 144.

[6]Ibid., 2.

[7]Ibid., 3.

[8]Ibid., 4.

[9]Steven R. Weisman. “Villard House, City Landmark, are Purchased by Archdiocese: Villard Houses Bought

by Archdiocese,” New York Times, March 12, 1971.

[10]Ibid., 2.

[11]Ibid., 3.

[12]Paul Goldberger. “Villard Houses: Option for the Future,” New York Times, December 9, 1974.

[13]Ibid., 2.

[14]Peter Dragadze. “The House that Henry Built and Harry Topped,” Town & Country, 1980, 142-142, 144.

[15]Ibid., 2.

[16]Ibid., 3.

[17]Paul Goldberger. “Villard Houses: Option for the Future,” New York Times, December 9, 1974.

[18]Dudle Clendinen. “Palace Opens, with a Few Reservations: Good Wises from Staff the Helmsley Palace, Still mostly Unbuilt, has its Grand Opening Rooms Tested Earlier Computer-Controlled Locks,” New York

Times, September 16, 1980.

[19]“Display Ad 115 – No Title,” New York Times, May 29, 1983.

[20]Ibid., 2.

[21]Dudle Clendinen. “Palace Opens, with a Few Reservations: Good Wises from Staff the Helmsley Palace, Still mostly Unbuilt, has its Grand Opening Rooms Tested Earlier Computer-Controlled Locks,” New York Times, September 16, 1980.

[22]“Lotte Hotels takes over New York Palace,” Hotel Management, October 21, 2015, 58.

[23]“Elizabeth Everett, Brian Krisberg,” New York Times, June 19, 2016.

My name Thomas Houghton Villard My Father Oswald Garrison Villard JR During a tour my father and I visited The Villard Hotel We signed into the church across the street this was 60yrs ago The Hotel was covered with Ivy you couldn’t see much from the outside and the building was still under repairs. I was adopted into the Villard family the son of Oswald G. Villard junior He showed all over New York as his son. Wow what a long time ago to remember what great times I had with him