Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton’s Connections to the Watering Place

Portrait of Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull in 1806, copied from a portrait by Guiseppe Ceracchi. This portrait currently resides in the National Portrait Gallery.

Alexander Hamilton is most remembered for The Federalist Papers, founding the Coast Guard, creating the Nation’s Treasury, serving the fledgling United States of America both in the military and as the first Treasury Secretary—all moments portrayed in the hit musical, Hamilton. There are questions about Hamilton’s alleged involvement in the Doctors’ Riot, but he his connections to Dr. Richard Bayley are more concrete. He is even linked to the Seton family through some banking paperwork for the Bank of New York. However, Alexander Hamilton’s influence can be felt in the medical field in America and in the events surrounding the major players of the Watering Place.

Hamilton’s Interest in Medicine

Alexander Hamilton attended King’s College (now Columbia University) shortly after his arrival to America. Hamilton did not have political aspirations when he started school, as illustrated by Ron Chernow: “At first, Hamilton aspired to be a doctor and attended anatomy lectures given by Dr. Samuel Clossy (51). This interest in medicine would remain with Hamilton for the rest of his life. Hamilton’s initial medical leanings would lead him to focus on medicine and cutting-edge medical treatments, particularly treatments for infectious diseases. He favored methods considered “unconventional” for the time, such as the avoidance of bloodletting when it came to treatment for yellow fever. This initial interest in medicine could serve as evidence for Hamilton’s alleged involvement with the infamous Doctors’ Riot of 1788.

The Doctors’ Riot of 1788

The Doctors’ riot of 1788 centered on the issue of cadavers used for dissection and study by medical students. Cadavers were difficult to come by, so medical students typically had to steal body parts from graves; these body parts would come from the poor or, most commonly, the African American population (de Costa). There was a “potter’s field” close to the former King’s College, Columbia College at this point in time, which became an easy target for the medical students to pillage for bodies for dissection. This potter’s field was known as the “Negroes Burial Ground” (Lovejoy). In 1788, newspapers began publishing accounts that bodies were being stolen from this field by the medical students at Columbia College, which was the only medical college in New York at the time. Also, according to Joel Tyler Headley, “in the winter of 1787 and 1788, medical students of New York City dug up bodies more frequently than usual, or were more reckless in this mode of action.”

In response to these circulating stories, the African American community, both free and enslaved, appealed to the Common Council in the city, not for the body snatching to stop, but for the grave-robbing to be conducted with the dignity the bodies that these medical students were taking body parts from were due (Lovejoy). Unfortunately, this call for redress was ignored. It was not until on February 21, 1788, when “the Advertiser printed an announcement saying that the body of a white woman had been stolen from Trinity Churchyard” that the public became concerned about the body-snatching (Lovejoy). This announcement turned the tide and began rousing the public to riot, though the actual Doctors’ Riot did not start until April 1788.

The actual events that sparked the riot are up for debate, but the location is relatively static: New York Hospital. Here are the events as described in Joel Tyler Headley’s The Great Riots of New York:

In the spring [April 1788], some boys were playing in the rear of the hospital [New York Hospital], when a young surgeon, from a mere whim, showed an amputated arm to them. One of them, impelled by curiosity, immediately mounted a ladder that stood against the wall, used in making some repairs, when the surgeon told him to look at his mother’s arm. The little fellow’s mother had recently died, and filled with terror, he immediately hastened to his father, who was a mason, and working at the time in Broadway. The father at once went to his wife’s grave, and had it opened. He found the body gone, and returned to his fellow workmen with the news. They were filled with rage, and, armed with tools, and gathering a crowd as they marched, they surged up around the hospital.

De Costa’s account names the “young surgeon” as John Hicks, and he became the target of the riot in numerous accounts. As the hospital was stormed, numerous samples were destroyed, and body parts were allegedly shown to the crowd from the windows, which only incensed the crowd more. (de Costa). The rooms where the incident that lead to the riot allegedly took place belonged to Dr. Richard Bayley. Bayley allegedly tried to save some of his specimens and work, but unfortunately it was destroyed. Mayor James Duane arrived with the sheriff, who took the doctors and medical students to jail to keep them safe from the mob (Lovejoy).

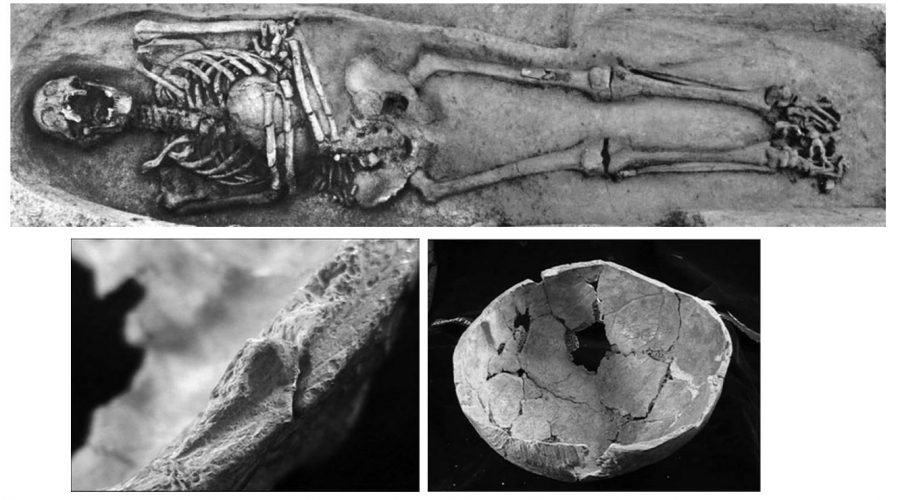

African Burial Ground Victim of Dissection

A 19 – 30 year old non-African “Caucasian” man buried in the African Burial Ground in lower Manhattan, a cemetery that had been forgotten but rediscovered in 1989 during the construction of a federal office building. There were several unusual characteristics about this skeleton. This skeleton was buried without a coffin along with a few other skeletons. But unlike the other’s the top of the skull was surgically removed and placed under the arms as if clutching it for perpetuity. Although it is difficult to know for certain this individual may very well have been a victim of the grave robberies that were common in the late 1700s for clandestine dissection by medical students. The lower images shows saw marks on edge of the skull, supporting the hypothesis that this individual underwent surgical dissection. The African Burial ground was closed in 1794, shortly after the1788 Doctor’s Riot. This individual may have been taken from his original burial site and hastily reburied in the African Burial Grounds.

A 19 – 30 year old non-African “Caucasian” man buried in the African Burial Ground in lower Manhattan, a cemetery that had been forgotten but rediscovered in 1989 during the construction of a federal office building. There were several unusual characteristics about this skeleton. This skeleton was buried without a coffin along with a few other skeletons. But unlike the other’s the top of the skull was surgically removed and placed under the arms as if clutching it for perpetuity. Although it is difficult to know for certain this individual may very well have been a victim of the grave robberies that were common in the late 1700s for clandestine dissection by medical students. The lower images shows saw marks on edge of the skull, supporting the hypothesis that this individual underwent surgical dissection. The African Burial ground was closed in 1794, shortly after the1788 Doctor’s Riot. This individual may have been taken from his original burial site and hastily reburied in the African Burial Grounds.

Bottom two figures from Blakey, M. L. & Rankin-Hall, L. M. Eds. (2009). The New York African Burial Ground: Unearthing the African Presence in Colonial New York, Volume 1, p. 7. Washington D.C.: Howard University Press

Top figure from The Skeletal Biology of the New York African Burial Ground, Part 2: Burial Descriptions and Appendices, p. 118.

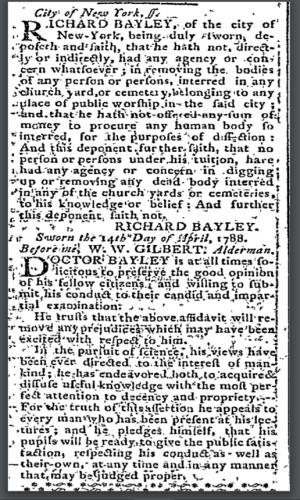

Newspaper article of Dr. Richard Bayley’s sworn statement regarding the Doctors’ Riot.

A Grand Jury convened for the purpose of investigating the riot, but Hicks never appeared in court (de Costa), and “there is no record of anyone being convicted” (Lovejoy). In the days following the riots, doctors published notices

stating that they did not participate in or encourage body-snatching for dissection; Dr. Richard Bayley published one such notice. On April 15, 1788, his sworn statement appeared in The New York Journal and Daily Patriotic Register “that he hath not, directly or indirectly, had any agency or concern whatsoever; in removing the bodies of any person or persons interred in any churchyard or cemetery belonging to any place of public worship in the said city” (“City of New York Ss.”).

Hamilton and the Doctors’ Riot

Alexander Hamilton’s alleged involvement in the Doctors’ Riot involves his engagement with the rioters on the second day of the riot. The mob made its way to Columbia, still searching for medical students and doctors (de Costa). Hamilton allegedly pleaded with the crowd on the front steps of the school for calm and a return to order (Lovejoy). According to this account, “Hamilton was shouted down and pushed past” as the mob searched for evidence of dissection (Lovejoy).

Hamilton had multiple connections to the Doctor’s Riot; as an alumnus of Columbia, his alleged appearance at the steps of the school to plead for peace seems plausible. He corresponded with Dr. Richard Bayley (albeit at a later date post-riot), but he was also friends with Mayor James Duane. Duane was one of the delegates selected to represent New York during the First Continental Congress, along with John Jay, writer of several entries in the Federalist Papers (Chernow 57). Hamilton wrote to Duane frequently during the Revolution, and he discussed ideas for a future American government and even a centralized banking system in a September 1780 letter (Chernow 138-139, 232, 347).

Another account of the riot alleges that John Jay was present at the riot with General Baron von Steuben (Lovejoy). General von Steuben was hit with a brick, which is reported in several accounts, but allegedly, John Jay was hit with a rock and injured, a fact which has not been conclusively proven (Lovejoy).

Hamilton and Dr. Richard Bayley

While Dr. Richard Bayley was serving as the Health officer to the City of New York, he petitioned the city to pass a law to prevent the spread of disease by quarantining ships, which was passed on April 1, 1796 (“To Richard Bayley”). Hamilton, along with Richard Harrison, the United States Attorney for the District of New York, wrote Bayley to check a ship that arrived from overseas for fear of the spread of infectious disease (“To Richard Bayley”). In fact, Hamilton seems to have been in contact with Bayley quite a bit regarding ships arriving in the United states with possibly infectious passengers, as Hamilton saw fit to notify President George Washington of one such case with the French (“To George Washington”).

Hamilton and William Seton

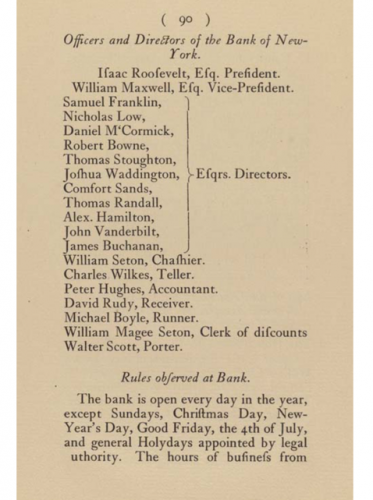

Alexander Hamilton also corresponded with William Seton, Saint Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton’s father-in-law. Seton was the cashier of the Bank of New York, and they shared correspondence regarding banking issues with the new Bank of New York, which faced early opposition (“From William Seton”). Hamilton was one of the directors of the Bank of New York, so he would have been in constant contact with the bank’s cashier.

Initial directors of the Bank of New York

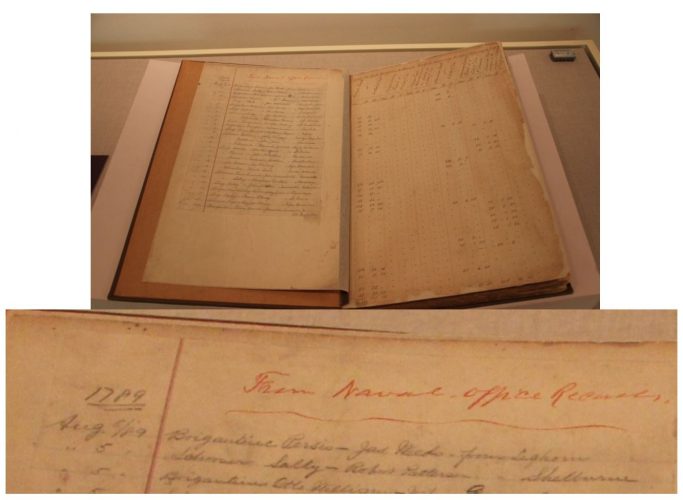

Connections: The US Customs Office of the Treasury Department, William Seton, and the Quarantine Grounds

“The Brig Persis sailed into New York Harbor on August 5, 1789 carrying goods destined for merchant William Seton. He would pay a fee of $774.71 to import goods. This payment would be the first Customs duty ever collected by the United States Government.” The National Archives Educational Updates https://education.blogs.archives.gov/2014/06/25/the-importance-of-u-s-customs/, downloaded 12/27/16

New York Vessels Arrivals August 1789 – March 1795. Was on display at the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House at 1 Bowling Green, home of the National Archives at New York City (June- October 2014). The first entry reads: “August 5 1789 – Brigantine Persis – James Weeks from Leghorn” [Livorno, Italy]

In 1790 by an act of Congress, on the recommendation of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, the United States Revenue Cutter Service was established as an armed customs enforcement arm of the Treasury Department. The Revenue Cutter Service would operate out of the federal portion of the Quarantine Grounds at the Watering Place for over 6 decades.

Mary Katherine Evans

Seton Hall University English MA Program

Works Cited

“Alexander Hamilton and Richard Harison to Richard Bayley, 19 July 1796,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified November 26, 2017, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-20-02-0173. Accessed 14 Nov. 2017.

Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Books, 2004.

“City of New York, Ss.” The New York Journal, and Daily Public Register, 15 Apr. 1788, vol. XLII, no. 89, p. 3. Early American Newspapers Series I (1690-1876), http://phw02.newsbank.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/cache/ean/fullsize/pl_012102017_1512_04595_55.pdf. Accessed 14 Nov. 2017.

De Costa, Caroline and Frances Miller. “American Resurrection and the 1788 Doctors’ Riot.” The Lancet, vol. 377, no. 9762, 22 Jan. 2011. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2811%2960083-4/fulltext. Accessed 9 Dec. 2017.

“From Alexander Hamilton to George Washington, [5 November 1796],” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified November 26, 2017, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-20-02-0248. Accessed 9 Dec. 2017.

Headley, Joel Tyler. “Chapter IV: Doctors’ Riot, 1788.” The Great Riots of New York. 2nd ed. Andrews UK Limited, 2012. Ebook. http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzk5NDQ0NF9fQU41?sid=7ca97dc4-60fd-4975-a704-ebe3e58fc392@sessionmgr4007&vid=0&format=EK&rid=2. Accessed 9 Dec. 2017.

Lovejoy, Bess. “The Gory New York City Riot that Shaped American Medicine.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, 17 Jun. 2014. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/gory-new-york-city-riot-shaped-american-medicine-180951766/. Accessed 14 Nov. 2017.

“To Alexander Hamilton from William Seton, 27 March 1784.” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified November 26, 2017, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0341. Accessed 10 Dec. 2017.