By Christopher Hann

ON JUNE 21, 2018, William Connell walked into an antiques shop in Amalfi, a picturesque Italian port on the northern shore of the Gulf of Salerno. Connell, a professor of history and the La Motta Endowed Chair in Italian Studies at Seton Hall, had come to Italy to discuss The Routledge History of Italian Americans, a recently published book he had conceived and co-edited, at the annual literary festival in Salerno. While in Salerno, Connell boarded a ferry to Amalfi, where he toured the medieval cathedral in the Piazza del Duomo. Back at the ferry terminal, he learned there would be a wait for the boat that would return him to Salerno, so he ducked into a nearby antiques shop, looking for books to help bolster Seton Hall’s Valente Italian Library.

Connell had already cultivated a distinguished career as a historian and researcher with an interest in the Italian Renaissance. He had written a book on the Renaissance political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli and published a translation of Machiavelli’s iconic The Prince. He received a $200,000 Andrew Carnegie fellowship grant that funded three years of research for, among other projects, a study of migrant labor practices in Renaissance Florence.

His new book had been an ambitious project, involving 40 writers and culminating in a 692-page tome. It earned him a U.S.-Italian Fulbright Commission 75th Anniversary Prize, for which he was feted last year in a ceremony in Rome.

Inside the antiques shop in Amalfi, Connell came upon four manuscripts — three written in Italian, one in Latin — two of them, he quickly discerned, from the 16th century. “There were these four old manuscripts, bound, so they looked like books,” Connell recalls, “but when I opened them up, they were handwritten manuscripts.”

It’s worth noting that Connell had walked into the shop bearing all the scholarly skills and subject matter mastery honed over a career in which he’d spent countless hours poring over centuries-old texts, some of them written in medieval Latin, with scribbled notations or abbreviations, in archives and libraries across the Italian peninsula. “So I have paleographic expertise, I guess one could say,” he notes.

And though he did not have the time in the shop to read the texts at length — the ferry, after all, was on its way — Connell was confident they were worthy of their sale price of 500 euros each, the rough equivalent of $2,000 for all four. He brought the manuscripts home.

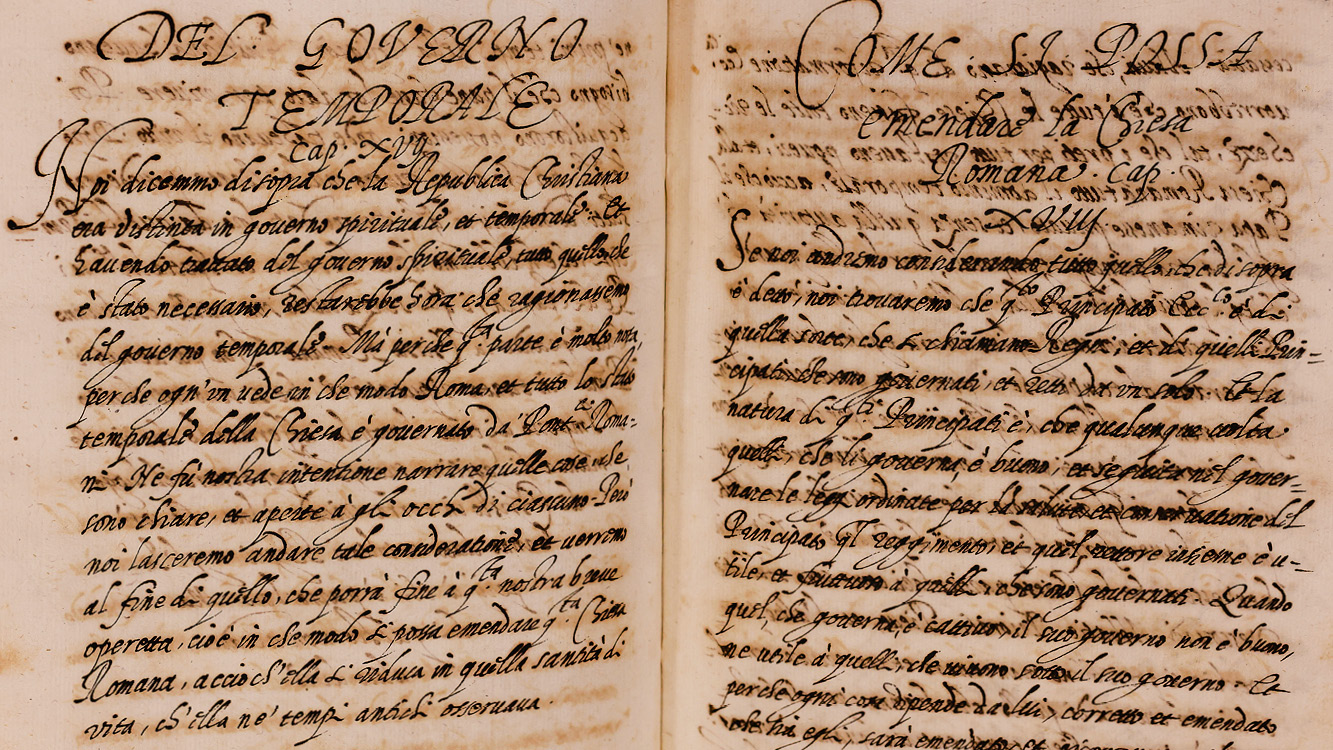

Back in South Orange, Connell embarked on the painstaking task of identifying the authors, translating the texts and, to ensure they had not been stolen or forged, verifying their provenance. It was not long before one of the texts stood out for the extraordinary nature of its content. Written in 1541, titled Della Republica Ecclesiastica (Of the Ecclesiastical Republic), and dedicated to Niccolò Ridolfi, an exiled Florentine cardinal, the manuscript bore only its author’s initials — M.D.G. The text contained a well-researched history of the Catholic Church, but with a surprise ending.

The final chapter was titled “Come si possa emendare la Chiesa Romana” (How the Roman Church can be amended). The author was proposing a radical realignment in the hierarchy that would reduce papal powers and introduce a more republican constitution to Church affairs. This was necessary, the author argued, because a series of tyrannical popes had exercised rampant abuses of power.

The author recommended that sitting cardinals, not the pope, appoint new cardinals. New bishops would be elected by the clergy, in consultation with the laity in each diocese. And the bishops, the author made clear, should be resident in their dioceses. During the Renaissance, Connell says, it was not unusual for bishops and cardinals to rule over multiple dioceses, even, in some cases, ones that were overseas. According to the reform proposed in Della Republica Ecclesiastica, bishops would be confined to a single diocese.

Reading the text, Connell’s eyes widened. He recognized the thorough manner in which the author had recounted Church history through the centuries, and the author’s concluding manifesto struck him as entirely novel.

“The idea of making it a republic,” Connell says of the author’s conclusion, “turning the pope into a figurehead, like the doge of Venice, having the Church run by the College of Cardinals as a senate, was something that I had never encountered in my studies of Italian history, studies of Church history, and so forth. So right away that triggered the interest.”

But who was the author?

Connell was aware of a prominent 16th-century writer — a friend of Machiavelli, in fact — who was a brilliant scholar, a professor of Greek, a leading thinker of the Italian Renaissance, and a Florentine exiled by the Medici regime who later resettled in Rome. He had written two books on the proper governance of the republics of Florence and Venice, published in 1538 and 1540, respectively. His name was Donato Giannotti.

A former professor of Connell’s had published a book on Giannotti’s correspondence in Latin, a book Connell happened to own, and in its pages he came across a letter that Giannotti had written to Cardinal Ridolfi in 1541. Giannotti told Ridolfi he was close to completing a book dedicated to the cardinal, and he identified the book by its title: Della Republica Ecclesiastica. The author’s identity, Connell says, “was nailed down by that letter.” As for the M in the initials on the manuscript, Connell says it stood for Messer, a courtesy title, reserved for Renaissance-era elites, that translates to “My Lord.”

Connell now knew he possessed a significant historical document, for he understood Della Republica Ecclesiastica to be the first modern history of the Catholic Church to be written by a layperson.

MONSIGNOR THOMAS GUARINO, a professor emeritus of systematic theology at Seton Hall, describes Connell’s research into Della Republica Ecclesiastica as “a terrific piece of scholarship” that “gives great honor to the University.” Last fall, in a joint presentation, Guarino compared the positions taken by Giannotti in the 16th century with the reform efforts of the Roman Catholic Church in the 20th and 21st centuries, in particular the Second Vatican Council of the 1960s. Of Connell, Guarino says: “I have enormous respect for his scholarship.”

What struck Connell most profoundly about Giannotti’s approach to Church reform was its nearly total disregard for religious doctrine and its focus instead on the best practices for governing the Church.

“When things were governed in this way,” Giannotti wrote, “ecclesiastical ranks would be given to honored people, and consequently their governments would be good, so that throughout the world priests would be loved and honored, and not as they are today hated and vilified.” He continued: “And if the government were to proceed in the way mentioned, the wealth of the Church would not be odious, because it would not be converted into the private conveniences of the pontiffs.”

Connell knew Giannotti to be an advocate for the distribution of authority — his earlier history of Venice had lauded the decentralized system of government in place while the city rose as an economic power. No doubt Giannotti’s own experience in Florence, where he was vilified under the tyranny of the Medicis, colored his views on autocracy.

“So he doesn’t try to justify his reform on the basis of Scripture,” Connell says. “He justifies his proposed reform on what he thinks will work best. And he sees a republican government working well in Venice, which he knew. And he’s studied all of the examples, from ancient Greece and ancient Rome, of republics and what things worked and didn’t work in those histories.”

Giannotti was both a Church insider and outsider. He served in non-clerical positions under his patron, Cardinal Ridolfi, and despite his criticism of papal abuses, he was very much a defender of the Catholic Church, particularly in the wake of the Protestant Reformation earlier in the 16th century.

“In fact,” Connell says, “the author cares about the Church functioning and surviving as an entity, rather than really worrying about questions of doctrine — that is, how people are saved. And he doesn’t think the Church should suffer division, or become a victim to abstract disputes, like the one with Martin Luther.

“In his history of the Church, Giannotti leaves aside accounts of miracles and the lives of saints. He wants the Church to be well governed. I remember thinking that this could be imagined as something like the critical report a consultant for McKinsey and Company might have written.”

While in the employ of Cardinal Ridolfi, Connell says,Giannotti wrote “ironically” about having to eat his meals “at the ringing of the bell.” At one point, Giannotti is given a prebend — regular income drawn from Church revenue.

“And he writes to a friend that he’s glad he won’t be called Reverend or have to dress like a priest in accepting the prebend. But he certainly values the Catholic Church. He’s strongly on its side against the Protestants. And he wants it to succeed.”

Giannotti wrote that the book was written at the behest of Ridolfi, and Connell surmises that because it espoused sweeping reforms that would have been fiercely opposed by powerful Church authorities, and because it was never published, the book would have been circulated among only a trusted few.

At the conclave of 1549-50, Giannotti served as Ridolfi’s conclavista — his secretary, or campaign manager — who would go from cell to cell passing messages to the cardinals who were assembled to elect a new pope. Ridolfi, in fact, was a favored candidate for the papacy, which leads Connell to conclude that few people, and certainly no one in a position of authority within the Church, knew of the book he had directed Giannotti to write less than a decade earlier.“ If it had become known that the cardinal had asked such a book to be written, proposing to turn the Church into a republic, he would have had a difficult time of it,” Connell says.

At that very conclave, just as Ridolfi appeared to be on the verge of ascending to the papacy, he suddenly took ill. Within days, he was dead. Poisoning was suspected, and later confirmed by an autopsy, a turn of events still debated by Church historians half a millennia later.

IN MAY 2023, nearly five years after Connell had walked into the antiques shop in Amalfi, Della Republica Ecclesiastica was published. The 480-page book includes an 85-page introduction by Connell.

“[T]here is an undeniable nobility in the attempt of Giannotti to apply historical criticism in a rigorous way to the Church,” Connell writes, “not for erudition’s sake, nor to promote a set of doctrinal beliefs, but to improve an institution he hoped would become and remain a bulwark against tyranny.”

Christopher Hann is a freelance writer and editor in New Jersey.