By Dermot Quinn

As Dermot Quinn explains in the newly published Seton Hall University: A History, 1856-2006, the University owes its foundation to three central figures: Bishop James Roosevelt Bayley, Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton and Father Bernard McQuaid.

Quinn, professor of history at Seton Hall, worked on the account for more than 15 years, having been urged to write it by president emeritus Monsignor Robert Sheeran.

Of Seton Hall’s inception, Quinn writes “In 1856 James Roosevelt Bayley, Roman Catholic Bishop of Newark, founded a school in Madison, New Jersey, calling it Seton Hall College in honor of his aunt, Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton. The name was a gesture of piety and a statement of intent. By honoring the greatest promoter of Catholic schools in early nineteenth century America, Bayley wished to continue her work of building American Catholicism through education, charity, and moral instruction.

“The new school was thus, in various senses, an act of faith. In the first place, it kept faith with a remarkable woman. In the second place, it promoted a particular faith, Roman Catholicism, and a particular people, the Catholics of New Jersey. Seton Hall was to cater for a new flock spiritually and socially, giving it a place in the world and, perhaps, in the world to come. “‘The school-house has become second in importance to the House of God itself,’ he wrote shortly before he became bishop in 1853.”

Bishop Bayley was aided immeasurably in this endeavor by Father McQuaid, a man of “indomitable energy and zeal” who deserves credit for driving the fledgling educational enterprise forward despite divisions that arose at times between the two men. McQuaid served as Seton Hall’s president from its inception — raising money, furnishing the school, welcoming and guiding students — until 1868 (except for 1857 and 1858, when Father

Daniel Fisher presided).

The excerpt on the following pages chronicles Seton Hall’s earliest days, documenting the move from Madison

to South Orange and providing a slice of life as to what the first students encountered at the school.

The text includes the footnotes as numbered in the book, which are referenced at the end of the excerpt.

A New Home

Success depended on leadership and here the story took a turn for the better. Fisher relinquished the presidency in 1859, forcing Bayley to turn again to McQuaid. “Have been obliged to re-appoint the Rev. Father McQuaid to the Presidency of the College,” he wrote in his diary on July 16, 1859. “He is still retaining the pastorship of the Cathedral. It is more difficult to find a good College Pres. Than to find a good anything else in this world. All that the College needs to ensure its permanent prosperity is a President. Everything else is there.”41

If there is a hint of reluctance here, a sense of anticipated difficulty with a deputy now assured of his indispensability, McQuaid’s return nonetheless brought nothing but benefit to Seton Hall. Bayley deserves credit for it.

Coinciding with this second act and perhaps prompting it was a recognition that Seton Hall had outgrown its original premises. As early as 1857, Bayley was complaining of “the smallness of the College for Ecc[lesiastical] Students.”42 In 1859 he declined admission to Samuel Seaman from Philadelphia: “cannot receive him, have 30 Ecc. Students at present: would give him a situation at the College but have no place for him.”43

Students wishing to study for the priesthood needed to be closer to Newark to take part in diocesan liturgies, and proximity to New York would also encourage wealthier parents to send their boys to the college.

“The object I have in view,” he told priests in May 1860, “is to enlarge the present institution — to unite to it as soon as possible a Theological School similar to that connected with Mount S. Mary’s near Emmitsburg — and by bringing it nearer to the Episcopal City to increase its usefulness and to render it more readily accessible to the Clergy of the diocese for retreats, Conferences, and other Ecclesiastical purposes.”44

With numbers stuck at about sixty, Bayley and McQuaid had to find another place at a reasonable price, bearing in mind that other institutions (such as the recently established North American College in Rome) were also seeking support.45 Nonetheless, a site was secured, almost by accident:

One bright day in the early spring of 1860, Bishop Bayley and Father McQuaid were returning from a long drive over the Orange Hills from what had proved a fruitless search for a location for the new college; rather discouraged, they were driving slowly homeward over the South Orange and Newark turnpike, when Bishop Bayley’s attention was attracted to a large white marble villa surrounded by superb grounds and stately trees. He turned to Father McQuaid and said “do you think that property can be purchased.” “I don’t know, but we’ll try,” answered the young priest with assurance and ready promptness. For Father McQuaid to will, was to accomplish, when he once set to work with a purpose, and despite several obstacles it was not long before the property was bought and the deed transferred to Bishop Bayley … on April 2, 1860.46

Bayley recorded the transaction laconically: “New College. Purchased the House and Farm known as the Marble House near South Orange for $35,000: the house was built by a person named Elphinstone, who spent some $40,000 on it and failed before it was completed. Intend to give the property at Madison to the Sisters of Charity & remove the College to this new place.”47

The Elphinstone house and over sixty acres of land in South Orange were a bargain. Moreover, conveying the Madison property to the Sisters of Charity was not a gift. They paid $25,000 for it, which included the forty-eight acres purchased in 1854 and an additional thirteen acres bought in 1859. (The building and land formed the nucleus of a convent and, later, the College of Saint Elizabeth.) Bayley asked a real estate agent, Michael MacEntee of Vailsburg in Newark, to handle the sale, knowing that there would be local opposition had the purchaser been known as a Roman Catholic bishop.

Bayley’s reference to the Elphinstone failure is obscure. It may have been financial, personal, or domestic, the inability of two brothers of that name to live under the same roof. (The brothers, it should be added, were not the vendors; the property belonged to a Mr. Charles Osborne of Exchange Place, New York.) At any rate, the farm alone was worth more than the price Bayley and McQuaid paid for house and land together.

McQuaid noted in 1886 that “the value of the land has greatly appreciated since I bought it in 1860 … the buying price was about $500 per acre, with the Marble Building thrown in [for nothing]. The land today, about sixty-eight acres, should be worth from two to three thousand dollars per acre.”48 The village of South Orange added to the appeal, an hour by train from New York. With the Orange Mountains adding a touch of grandeur to the estate, the Elphinstone property overlooked “a beautiful country,” the College Catalogue of 1862 boasted, “noted for healthfulness” with “villas and mansions on every available site for miles around.”49 It was perfectly chosen.

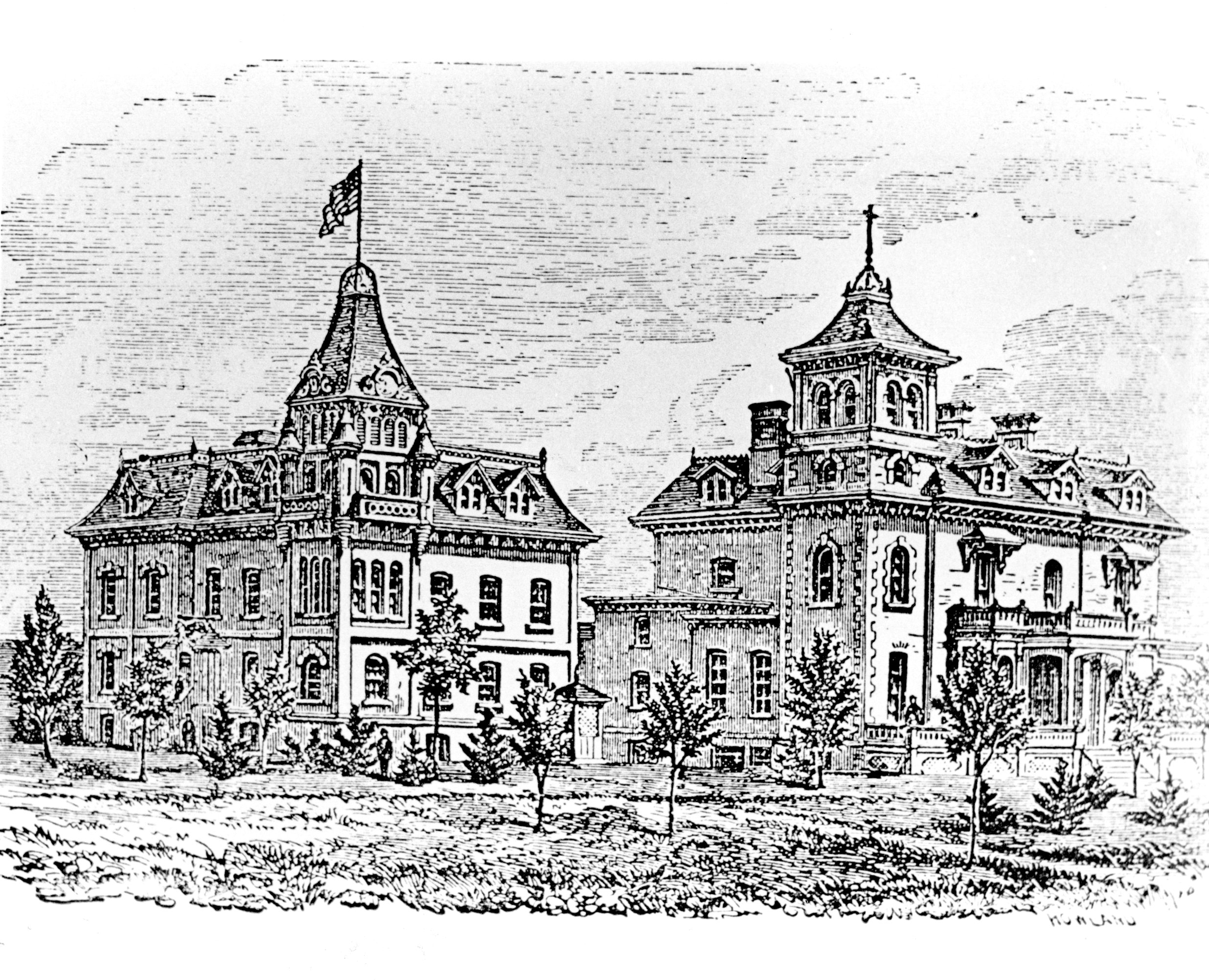

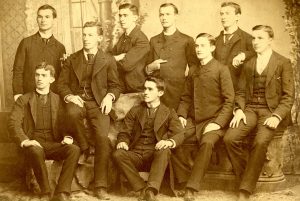

The removal of Seton Hall from Madison to South Orange was a diocesan event and Bayley made the most of it. Clergy and laity contributed $8,100 to an appeal launched in May 1860, enabling work to begin immediately on modifying the villa but insufficient to offset the purchase price. Almost as soon as the ink was dry, the Marble House was customized to serve the needs of seminarians with the addition of dormitories and a study hall. On May 15, 1860 Bayley laid and blessed a cornerstone — a “large number of people present — made an address”50 — for a new building to house the college proper as opposed to the seminary (whose independent life may be said to begin with the move to South Orange). On September 10, 1860, Bayley recorded that “the new college building at South Orange is finished and has opened,”51 which does scant justice to its extraordinarily rapid construction. This “College Building” — the first of several — housed fifty students taught by seventeen faculty members. A three-story building in brick with dormer rooms, two chimney stacks, and a pointed tower, it was to the left of the Marble Villa. The household was again under the Sisters of Charity.

The Marble Villa and College Building were set in pleasant surroundings of parkland, some well-tended lawns, and a couple of playing fields. The rest of the property consisted of a farm providing vegetables and milk for the college kitchen. In October 1864 a further purchase of farmland was made, adding to the supplies of fresh produce for the seminary. Long after Bayley and McQuaid were dead, this farm and its modest set of outbuildings would form the basis of a legal case that ended before the United States Supreme Court. But that is a story for a later chapter. In 1864, it produced fodder, not lawyers’ fees.

Academic Life

In South Orange as in Madison, Seton Hall’s curriculum was classical, linguistic, and mathematical with an emphasis on commercially useful subjects such as book-keeping. The purpose was to cover subjects from rudimentary to advanced level (some of the students were hardly even teenagers) with a view to future employment. There were four courses: Classical, English, French, and Mathematical. Students could not take logic, metaphysics, and ethics without first mastering the sixth and seventh years of the classical course. French was compulsory, Spanish and German optional. Pupils could do music, drawing, and painting, for which an extra fee was charged. Sport did not feature but games played a large if informal part in college life.

The classical course was textual. The first year was spent doing basic Latin grammar, the second year proceeded to Caesar’s Gallic Wars, elementary Greek, and Aesop’s Fables. By the third year students did Latin prose composition and were translating Sallust, Ovid, and Virgil’s Ecologues. In Greek, they studied the Anabasis of Xenophon. In the fourth year, the curriculum consisted of Virgil, Cicero, Xenophon, and Homer; in the fifth, Livy, Horace, Cicero, Demosthenes, and Aeschylus; in the sixth, Tacitus, Horace, Cicero, Euripides, and Longinus; in the seventh, Juvenal, Perseus, Herodotus, and Thucydides.

The mathematical course was a combination of theoretical and practical work taking in some hard science. After the gentle slopes of mental arithmetic and algebra, students climbed through plane, solid, and spherical geometry; trigonometry; surveying and navigation; analytical geometry; differential and integral calculus; mechanics and civil engineering; natural philosophy (that is to say, physics); chemistry; and astronomy. Anyone who mastered it could hope for a career in engineering, building,

the maritime industries, accounting, or commerce. The hard sciences proper consisted of physics, chemistry, and astronomy but not biology.

English covered a range of materials. Rudiments came first — reading, spelling, prose composition, the taking of dictation. Harder material followed — elocution, precepts of rhetoric and poetry, criticism of ancient authors, finally “English Classical Reading.” English covered more than the word suggested, taking in historical material (Hale’s History of the United States, Lingard’s History of England, Fredet’s Ancient and Modern Histories) and also (oddly) Geography.

French was the foreign language nonpareil. A number of students knew Spanish already and German was the first language of others. The course was linguistic rather than literary. Grammar, conversation, dictation, and composition came first, poetry and prose second. The catalogue announced that students would undertake “the Study of French Literature” but without specifying what: probably whatever took the professor’s fancy on a given day.

Every class assumed the truth of the Catholic worldview. Astronomy, for example, was taught as a subset of natural theology, English history as branch of counter-reformation apologetics, and so on. Catholic teaching itself also had to be imparted. Students were expected to master “in regular succession” the Small Catechism, Butler’s Catechism, Collot’s Doctrinal and Scriptural Catechism, and Lectures on the Doctrines and Evidences of the Catholic Church. These exercises were reinforced in the sixth and seventh years by logic, metaphysics, and ethics.

Not every student undertook every course. The early curriculum was high school standard, the later stages more advanced. One option was to attend Seton Hall for a few years, then leave to find work. Getting a degree was not necessarily a goal. Those intent on ordination stayed longer. To receive a diploma, a student had to persevere for seven years. “Candidates for the degree of A.B.,” said the catalogue of 1861–62, “must undergo a public examination in the full course of studies pursued in the College.” Their scrolls were hard won.

Life outside the classroom was equally tough. Discipline and moral wariness were the watchwords:

No student ever leaves the College grounds without a teacher. Leaving the College grounds after night-fall subjects the student to expulsion.

The use of tobacco is forbidden …

No books of any kind can be held by the Students, unless by permission of the President.

Students are not allowed to receive newspapers, except for their Reading Room, which is under the direction of the President.

No correspondence is permitted, except under cover, to and from parents and guardians; and the President will exercise his right to examine all letters, as, in his judgment, it may be necessary.

No student of low and vicious habits will be retained in this College …

The number of letters scrutinized cannot be known; few enough, in all likelihood. The interdiction of “books of any kind” was designed to perfect reading, not prevent it. Cheap novels were disdained and anything worse, the surreptitious currency of dormitories, was ground for expulsion. Every school banned tobacco, less for reasons of health than safety. The rules were no better or worse than those of comparable institutions. Indeed, they were directed as much at parents as at pupils: “Parents have the right to withdraw their children at any time; they have not the right to interfere with the established discipline of the College; they have not the right to keep us and our punctual students waiting for laggards who want one more day of idleness.”52 McQuaid sought and achieved mastery over adults as well as children. He could be a torture at times.

The academic year lasted two terms of five months each, beginning on the last Wednesday in August and ending on the last Wednesday in June. Except for a ten-day vacation at Christmas and a brief exeat in May, students remained in college throughout the academic session. (Exceptionally, a student might also stay during summer.) Board and tuition, $225 per annum payable half-yearly the beginning of each term, included linen, laundry, the mending of clothes, but not the doctor’s fee ($5) or the cost of medicine. Other extras included music lessons ($50), drawing ($40), and tuition in German, Italian, and Spanish ($25 each). Students were allowed pocket money, lodged with the college treasurer, who disbursed or withheld it as he saw fit. Rich or poor, the typical student had an equipage fit for a prince: “On entering [he] must be supplied with four Summer suits, if he enters in the Spring; or three Winter suits if he enters in the Fall. He must also have at least twelve shirts, twelve pair of stockings, twelve pocket handkerchiefs, six towels, six napkins, three pairs of shoes or boots, and a napkin ring marked with his name.”53

Thus dressed, he faced an unknown but rule-bound world.

41. Bayley, Diocesan Diary, July 16, 1859.

42. Bayley Letter Book, October 29, 1857. ADN, 1.31.

43. Bayley Letter Book, March 5, 1859. ADN, 1.31.

44. Bayley circular, May 16, 1860. ADN 2.1, Bayley Papers 1836–1872, Box 1, Folder 23.

45. Bayley to Robert Seton, January 15, 1865, quoted in Yeager, Life, 203n163.

46. William F. Marshall, Seton Hall College Catalogue, 1895, 2, quoted in Robert J. Wister, Stewards of the Mysteries of God: Immaculate Conception Seminary, 1860–2010 (South Orange, NJ: Immaculate Conception Seminary, 2010), 24.

47. Bayley, Diocesan Diary, April 2, 1860

48. McQuaid to Archbishop Williams, April 13, 1886. Letter Book, Diocese of Rochester, 188.

49. Catalogue of the officers and students of Seton Hall College, 1861-1862, 5

50. Bayley, Diocesan Diary, May 15, 1860

51. Bayley, Diocesan Diary, September 10, 1860

52. Seton Hall College Catalogue, 1865–1866, 22.

53. Catalogue of the officers and students of Seton Hall College, 1861-1862, 7.

Excerpted from Seton Hall University: A History, 1856-2006

by Dermot Quinn, published February 10, 2023, by

Rutgers University Press. Copyright 2023 by Dermot Quinn.

All rights reserved.