By Christopher Hann

Jerry Walker’s life and his life’s work have been so intertwined with Jersey City that it might be easy to overlook how remarkable the contributions he’s made over decades to his hometown have been.

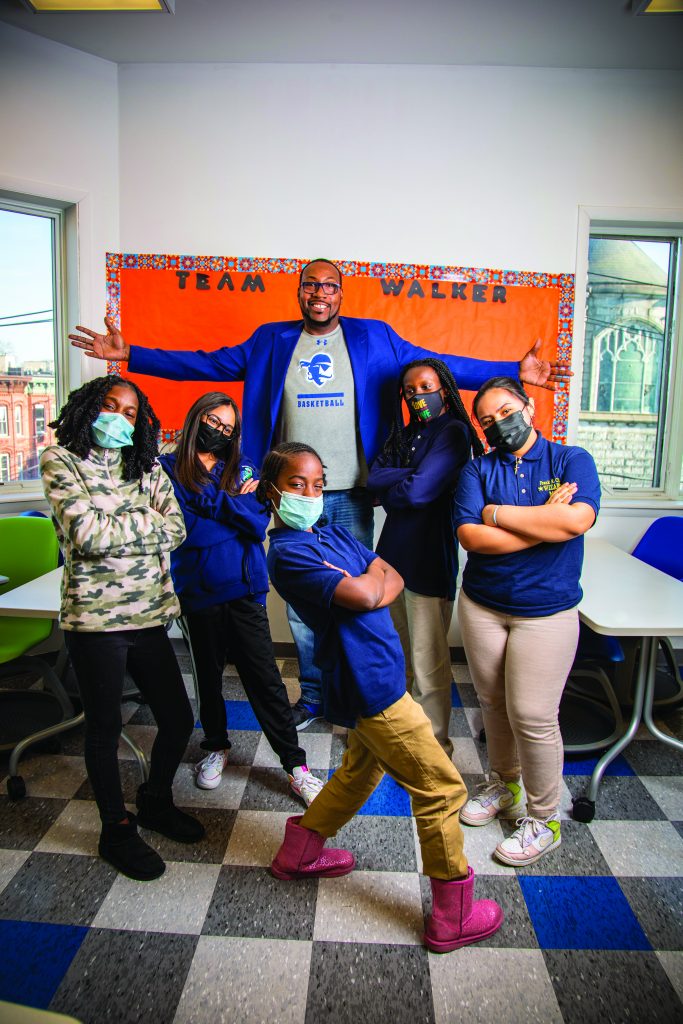

Seton Hall basketball fans will remember Walker as the workhorse power forward who started on three straight NCAA tournament teams in the early 1990s, and whose Pirates earned the BIG EAST Conference championship in 1993. But amid a nine-year career playing professional basketball in Europe, he founded Team Walker, an after-school education program made possible by a wide network of Seton Hall affiliations. Over the past quarter century, Team Walker has benefited hundreds of young people in need of a little extra support in the classroom, just as Walker had once needed.

Now Walker ’03 has set his sights on starting a vocational program for local kids who might not see college in their future but who might be motivated to pursue careers in the restaurant or hospitality industry; or as electricians, plumbers, carpenters; or heating, ventilation and air-conditioning contractors. Walker has raised $400,000 of the $557,000 needed to purchase a building he’s found and to get the program started. He has set an ambitious timetable, as he hopes to start the program in September. “We’re trying to give everybody the skills they need to provide for their family,” he says. “At the end of the day, we’re just trying to create a positive citizen.”

Walker’s life as a successful social entrepreneur with an educational focus — an entirely different sort of sports hero — might be unexpected. But he knows exactly where he found the motivation to improve the lives of so many young people in New Jersey’s second-largest city: His grandfather’s name was James Curry, but everyone knew him as Pop.

On the streets of the Bergen-Lafayette neighborhood, Pop Curry connected people. Walker remembers him as a behind-the-scenes political strategist who helped get several Jersey City mayors elected. “He had the ability to go to City Hall and bring 300 people with him and make some noise about equal opportunity.”

A builder by vocation, Pop Curry also ran a social service agency, the Lafayette Neighborhood Association, and an after-school program called Can Do — “where teenagers and young people could go for safe space and help with homework,” Walker says. Walker and his two siblings, his cousins, his friends and neighbors and classmates, all took part in his grandfather’s programs, including weeklong summer trips to faraway places — like Pennsylvania.

“When we first went out there, we were so scared,” Walker recalls of those trips. “We’d hear the crickets, and that was a little nerve-racking for a kid from the city.”

Walker was a big kid with a big heart, 6 feet 4 inches tall by the time he entered St. Anthony High School in downtown Jersey City. Even at a young age, he took an outsize interest in the welfare of others, and his grandfather took note. “I never liked bullies,” Walker says. “If one of my classmates was getting bullied by somebody, and [was] not so physical, I would offer to take it up for them. I didn’t like people taking advantage of people. I was always a caring person in that aspect, and [Pop] really loved that about me. When you care about other people, it’s a sign you’re going to do great things.”

Walker spent much of his childhood in the company of his grandfather. And while he might not have understood it at the time, the seeds of his grandfather’s influence were taking root. “He used to call me the little bump of knowledge,” Walker says. “At that time I was struggling in school, and I didn’t know what he was talking about. He saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself.”

At St. Anthony, Walker played under the demanding eye of legendary basketball coach Bob Hurley Sr., one of only four high school coaches inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Walker starred on the 1988-89 national championship team, considered by some the greatest collection of talent in the history of high school hoops. When it came time to choose a college, Walker ventured only as far as South Orange, not 20 miles from home. In his senior year, under Coach P.J. Carlesimo, he helped lead the Pirates to the most lopsided championship game victory in the history of the BIG EAST Tournament — a 103-70 shellacking of Syracuse.

In 1996, following the death of Pop Curry, Walker and his brother, Jasper, himself a basketball star at St. Peter’s University in Jersey City, started a summer basketball program in their hometown. It was the beginning of Team Walker, though the early years saw only choppy progress. Walker was still living and playing overseas for much of the year. When he came home each summer and organized the basketball program, he paid for much of it himself. Yet he always envisioned something bigger.

So when he retired as a player in 2002, Walker returned once again to Jersey City, not to bask in all that he had accomplished on the basketball court, certainly not to rest on his considerable laurels.

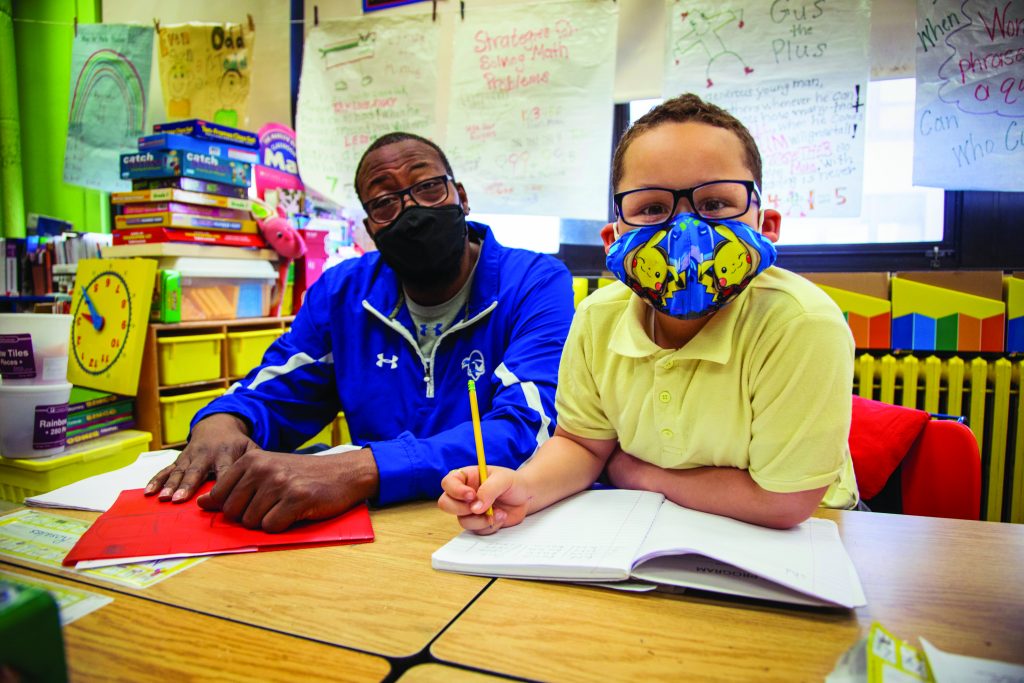

No, Walker had other plans. He wanted to incorporate an educational component into Team Walker’s mission, an aspiration drawn from his own experience at Seton Hall. As a wide-eyed freshman unsure of his own capacity in the classroom, he felt intimidated by the college-level curriculum and struggled to keep up. Today, more than 30 years after arriving on campus, Walker still invokes the name of his academic adviser, Robin Cunningham, ’78/M.A. ’84/Ed.S. ’96. Over time, and lots of study halls, she helped him believe he could achieve in the classroom. “She taught me a great deal,” Walker says. “She let me know I could compete in that arena, too.”

When he returned to Jersey City following his playing career, Walker also returned to the classroom, earning the final 20 credits he needed for his degree in communication (he minored in religion). Though reluctant to take part in the formal graduation ceremony, he says his mother, Carol Walker, a pastor, insisted.

“I learned a great deal at Seton Hall University,” Walker says. “How to be organized. How to be a leader. How to be somebody that’s not going to be easily deterred. You’ll always have obstacles. You just have to have confidence enough to work through any problem and find a solution. We won a lot of championships, but some of my classic moments came in the classroom.”

Walker’s Seton Hall experience taught him the value of education, and he wanted to pass on that lesson to the young people of Jersey City. “It took a long time for people to understand that Team Walker was about education,” he says. “Given my background, the real priority was the academic piece. Kids who are more educated make better decisions. They stand on their own two feet. You can’t take education away from somebody. The limbs are not going to last. The mind lasts much longer than that.”

In its early years, Team Walker operated on a limited budget, with volunteer tutors conducting lessons in local churches and P.S. 22, a public elementary school. But Walker had bigger dreams. He wanted a building he could call his own, which he knew would require a much greater financial investment. He reached out to his Seton Hall network, to on-campus personnel such as Cunningham and Athletic Director Bryan Felt ’97/ M.A. ’05, who both serve on Team Walker’s board of directors, and to business-world movers and shakers such as Jim O’Brien ’82, Robert Sloan, M.B.A. ’86, Leo Zatta ’78/M.B.A. ’84/M.S. ’86, and the late George Ring ’65/M.B.A. ’71. O’Brien and Sloan serve on Team Walker’s advisory board. Zatta has been chairman of Team Walker’s board for two decades. And Ring, according to Walker, provided the first six-figure donation to the building fund.

Like his grandfather, Walker is a connector of people. Zatta says Walker’s charisma — “he has the ability to pick up the phone and talk to anyone” — has been central to his success. “It’s really the personal touch that he has,” Zatta says.

That personal touch extends to the students enrolled at Team Walker, many of whom face challenges that can be hard to fully appreciate. Zatta remembers walking the halls of Team Walker with its founder one afternoon when a young girl, maybe 10 years old, ran up to Walker and wrapped her arms around him. Walker asked where she was supposed to be. “I’m supposed to be in class, Mr. Walker,” the young girl said. After she scampered down the hallway, Walker confided to Zatta that he was worried about the girl. Zatta asked why. “Her father was shot and killed two weeks ago,” Walker said.

In his quest to raise money for a new building, Walker also reached out to Michael Reuter, then the director of the Gerald P. Buccino ’63 Center for Leadership Development, now retired and director emeritus. Walker sought help from Reuter and his students in finding funding sources for Team Walker’s formidable expansion plans. The students took the challenge to heart, and several months later they presented a plan to seek a federal grant administered by the New Jersey Department of Education that was designed to support community learning centers. Over the past decade the grant has funded 50 percent of Team Walker’s $1.1 million annual budget.

“When he walks into a room,” Reuter says of Walker, “he lights up the room. People feel his energy, his excitement, his enthusiasm, and his passion for what he does. He loves the children. He will do anything for them.”

In May 2014, with a stable funding source in place, Walker presided over the official opening of Team Walker Learning Center, a three-story, 10,000-square-foot building on Communipaw Avenue in Jersey City. Today the center serves 170 students, from kindergarten through tenth grade, five days a week, with hundreds more involved in summer programs. Each member of the teaching staff is state-certified, and its roster of 22 full-time employees includes teacher’s aides in every classroom.

Team Walker recently received a pledge — $300,000 over three years — to create individualized programs for students with special education needs. Robin Cunningham will lead the program, and Leo Zatta says Team Walker is on track to begin in September.

To date, 155 former Team Walker students have earned college degrees, with two earning master’s degrees. Realizing those numbers represent a small percentage of the young people who could benefit from Team Walker’s programs, Walker started thinking about the value of vocational education and the need to help students who might not be bound for college.

Now he has found a building he wants to turn into a trade school and has identified a local minority-owned construction company to renovate it. And he continues his search for funding to get the school started.

Turning his ambitious vision into reality will be a challenge. But Jerry Walker has been there before. And he knows how to get things done. Pop Curry showed

him the way.

Christopher Hann is a freelance writer and editor in New Jersey.