Artifacts of the past on campus have captivating tales to share.

By Kevin Coyne

Objects can speak. If you walk through Seton Hall’s campus and listen closely, you can almost hear the narratives that the statues, paintings, books and buildings can tell about tens of thousands of lives over a period of more than 150 years.

Three people deeply steeped in Seton Hall’s history compiled a list of notable objects at Seton Hall: Monsignor Robert Wister, author of a history of Immaculate Conception Seminary, from which he recently retired as a professor; Dermot Quinn, a history professor who is writing the official history of the University; and Alan Delozier, the University’s archivist.

Some of these objects you may have encountered and then wondered about the stories that lay behind them. Others may have escaped your attention or are hidden enough that you

may need to seek them out.

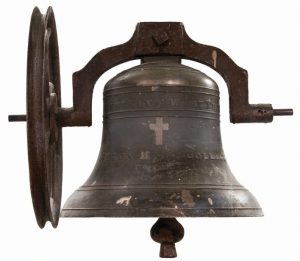

Seton Hall College Bell

Louis de Crenascol, chairman of the department of art and music in the late 1960s, was an antiques collector. When browsing in a Summit shop one day in 1969, he bent down for a closer look at a bronze bell sitting in a corner. He rubbed at the inscription until he could read it better: “Seton Hall College,” it read, “Madison New Jersey.” De Crenascol had stumbled upon the bell that had summoned the first five students to class at Seton Hall College when it opened in 1856 at the site of what is now St. Elizabeth University. By the end of that first year, the bell was ringing for 54 students.

Louis de Crenascol, chairman of the department of art and music in the late 1960s, was an antiques collector. When browsing in a Summit shop one day in 1969, he bent down for a closer look at a bronze bell sitting in a corner. He rubbed at the inscription until he could read it better: “Seton Hall College,” it read, “Madison New Jersey.” De Crenascol had stumbled upon the bell that had summoned the first five students to class at Seton Hall College when it opened in 1856 at the site of what is now St. Elizabeth University. By the end of that first year, the bell was ringing for 54 students.

How the bell landed in a Summit shop more than a century later and where it had been before that is still unknown. But the University bought it and hung it in the McLaughlin Library until that building was razed to make way for Jubilee Hall. The bell now hangs on the ground floor of Walsh Library, in the reading room of the Department of Archives and Special Collections — a silent link to the University’s birth.

Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton Window

When you walk into Presidents Hall, three stained glass windows gaze back at you from the stairway landing, lending the building an ecclesiastical air. Saint Joseph is on the left, the Virgin Mary in the middle, and on the right is the first American-born saint, Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, whose nephew, Bishop James Bayley, was the first bishop of Newark and the founder of Seton Hall.

When you walk into Presidents Hall, three stained glass windows gaze back at you from the stairway landing, lending the building an ecclesiastical air. Saint Joseph is on the left, the Virgin Mary in the middle, and on the right is the first American-born saint, Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, whose nephew, Bishop James Bayley, was the first bishop of Newark and the founder of Seton Hall.

She is dressed in dark purple, and around her head floats a green circle in a shape that seems to foretell an event that did not happen until more than a century after the window was made. “They just did it in the background color of green, but they did a halo shape because Bishop Bayley was probably figuring that Aunt Betty would become a saint,” Monsignor Wister says. “Nephew Jimmy thought so much of her that he was looking toward the future.”

Mother Seton was canonized in 1975, though Quinn is less convinced about the intentions behind the green circle. “I don’t want to pour cold water on it, but I’ve no evidence of that,” he says. “I’ve heard the story from different people, but I think you could record that as a piece of affectionate folklore.”

Stafford Hall Brick

The first building built specifically for Seton Hall College was simply called the College Building, and it was adjacent to Presidents Hall, home to the seminary. It later acquired a name: Stafford Hall, after Reverend John Stafford, president from 1899 to 1907.

The building was badly damaged by fire twice over the next century and a half (in 1886 and 1909), before it was demolished and replaced by a new building in 2014. “They were tearing the [old] building down. … It was the first building of Seton Hall College, and I said, ‘This is ridiculous, let’s save some of these bricks. Because once something’s lost, it’s gone,’” Monsignor Wister says. He gave Stafford Hall bricks to the president, the provost, the chairman of the board, the archbishop and the rector of the seminary. “And I saved one to be in some way installed in the building.”

And there it is, on the wall as you enter the new building, displayed behind glass with an explanatory letter — a brick that has seen and endured more than all the others around it.

SHP Initials

In the steady parade of students that marches up the steps inside the entrance of Mooney Hall each day — arriving on ROTC business or for meetings with counselors or academic advisors — how many notice the gray letters “SHP” set into the pink terrazzo floor, or know what they stand for?

Mooney Hall was built in 1909 as home to Seton Hall Prep. High school boys shared the campus with the undergraduates for generations — many of them living on campus as boarders as well — until the Prep moved into its own home in West Orange in 1985.

“Seton Hall College started as a kind of boys school and in a way the Prep is the continuing existence of that reality,” Quinn says. Those initials in the floor are a well-trod but often overlooked reminder of that.

Benjamin Savage Memorial

On the left wall of the chapel, just below the third and fourth Stations of the Cross, is a memorial to a man who spent half a century working at Seton Hall as groundsman, handyman and attender of cows: Benjamin Savage.

On the left wall of the chapel, just below the third and fourth Stations of the Cross, is a memorial to a man who spent half a century working at Seton Hall as groundsman, handyman and attender of cows: Benjamin Savage.

“Scarcely does he miss a day, but is always on hand in all kinds of weather, working at his beloved tasks. Yet in spite of these he is never too busy to give a hearty response to the merry greetings of his friends, the ‘boys,’” The Setonian wrote in 1924. “And if you strike up a conversation with him, you will find that in addition to his other accomplishments, Benny is also — a philosopher.”

When he died on All Saints Day in 1933, his insurance policy was valued at $5,000 and his estate was worth $10,719.83. He left it all to Seton Hall. “Who in life labored faithfully for the College and in death contributed generously to it,” reads the memorial plaque.

“That’s a lovely commemoration of a lovely piece of Seton Hall history,” Quinn says. “It’s one of those stories that gets all the brighter in the retelling.”

Bishop Bayley Plaque

Between two windows along the back wall of the sacristy in the chapel, beneath a crucifix and above the vesting table where priests prepare for Mass, hangs a small bronze plaque inscribed with Latin script. It caught Monsignor Wister’s eye one day back when he was a Seton Hall undergraduate — he spent two years on the South Orange campus, as was customary at the time, before going to the seminary at Darlington — and the chapel sacristan asked him to help serve Mass. “Back then, every priest and most seminarians could sight-read Latin,” he says, and he had already had four years of Latin at Marist High School in Bayonne.

Monsignor Wister saw Bishop Bayley’s name at the top of the plaque and “V. Mill” farther down, and as he read to the end he saw that it had been placed there in 1878 to mark a bequest by the bishop’s “very generous providence.” Bayley had left Newark and Seton Hall in 1872 when he was named archbishop of Baltimore, but he hadn’t forgotten the school he had founded. In his will, Bayley left “the sum of five thousand dollars as a perpetual bursary,” the plaque says in Latin. “Through this gift and by regulation, the sacrifice of the Mass will be offered once each month for the repose of his soul.”

The Sanctuary Light and the Altar Rail

When you walk into the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception, it’s easy to think you have stepped back into 1863, when Seton Hall had just 50 students, and before the steady procession of alumni returning for their weddings or the baptisms of their children had begun.

When you walk into the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception, it’s easy to think you have stepped back into 1863, when Seton Hall had just 50 students, and before the steady procession of alumni returning for their weddings or the baptisms of their children had begun.

But you haven’t. The sandstone building is the same — although 40 percent of the sandstone has been replaced. But almost everything inside is different, altered by a series of renovations reflecting changing ecclesiastical styles and the institution’s increasing prosperity. Marble statues replaced plaster, and the marble statues were in turn replaced by polychrome hand-carved wood. A baldachin rose over the altar. Stained glass filled the windows and expansive murals filled blank walls. Much of the wooden altar rail that stretched across the whole sanctuary was removed long ago, in a renovation of the 1970s, but two pieces remain, one on each side, and you can imagine those first 50 students kneeling there for Communion.

And when you look up from the altar rail to the tabernacle, a red light hanging on the wall beside it catches your eye — the gilt sanctuary lamp that has signaled the presence of the Eucharist ever since Bishop Bayley was saying Mass here. The lamp is the only piece of furniture that remains from the chapel furnishings of the 1860s; a tiny inscription “J. R. Lamb of New York” testifies to its maker.

One other feature might also be original, the small “eye of God” window at the peak of the chancel arch. “It reminds us that God is present in this Chapel and His benevolent eye is always watching over us,” Monsignor Wister wrote in his history of the chapel. “It also points us beyond the world to the new creation and draws us into the worship of God.”

The Pirate

There is a reason for the pirate on your Seton Hall sweatshirt — and on the rear window of your car, and cast in bronze in front of the athletic center, and grinning at you from every corner of the Seton Hall world. It is because in the ninth inning of a baseball game in Worcester, Massachusetts, on April 22, 1931, the Seton Hall team, three runs down and one out away from losing to a Holy Cross team whose fans were so sure of victory they had already started filing out, managed to score five runs, and, shockingly, won, 12-11.

“One of the sports writers was so excited at the sudden change of events that he exclaimed with disgust, ‘That Seton Hall team is a gang of pirates!’” the Newark Evening News reported. “When the Seton Hall team heard about it in the dressing room after the game they decided from then on they would call themselves the Pirates.”

The pirate has evolved over the years into what Monsignor Wister calls “that tasteful pirate symbol we have now.” The fiercer earlier version he prefers, salvaged from the old floor of Walsh Gymnasium, hangs now in the corridor outside the gym.

‘Setonia Stabbers’

As storied and beloved as basketball is at Seton Hall, the athletic team that scaled the greatest heights was the fencing team. “Our only national champions,” Delozier says.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, led by coach Gerald Cetrulo — a national champion at Dartmouth and a three-time Olympian — the Seton Hall fencers rarely lost. In 1939 and 1940, they won the East-West and United States Intercollegiate Fencing Titles — the de facto national championship before the NCAA established an official one. Their trophies are displayed in a glass case in the hall outside Walsh Gym.

Above the entries at each end of that hall are what look from a distance like faded black-and-white photos — the basketball team at one end, the fencing team at the other — but are actually grisaille murals, painted in shades of gray by Gonippo Raggi, the prominent ecclesiastical artist who painted the murals in the Immaculate Conception Chapel and designed all the interior decoration of the Cathedral Basilica of the Sacred Heart in Newark. The basketball players are standing in their mural, which Raggi painted when the gym opened in 1941, but the fencers are brandishing their swords, captured at the peak of their success.

Christmas Tree

The 60-foot Norway spruce that stands before Presidents Hall has long been garlanded for Christmas, but it wasn’t until 2010, at the suggestion of the new president, Gabriel Esteban, that switching on its lights — all 43,000 of them at once, in a joyous blaze — became a treasured campus ritual. It is a welcome burst of light in the dark and frazzled days at the end of the semester; students gather in their blue Santa hats to cheer the start of a series of holiday events that Best College Reviews ranked as the No. 1 college Christmas in the United States.

The 60-foot Norway spruce that stands before Presidents Hall has long been garlanded for Christmas, but it wasn’t until 2010, at the suggestion of the new president, Gabriel Esteban, that switching on its lights — all 43,000 of them at once, in a joyous blaze — became a treasured campus ritual. It is a welcome burst of light in the dark and frazzled days at the end of the semester; students gather in their blue Santa hats to cheer the start of a series of holiday events that Best College Reviews ranked as the No. 1 college Christmas in the United States.

In earlier Christmas seasons, before the tree was so tall and the lights so bright, other traditions prevailed. Animals snorted and bleated in a living creche outside the chapel: a sheep, a calf, a heifer and a donkey named Amos who was fond of chewing tobacco. “A student had to tend it, you can’t just leave these sheep by themselves, and the story goes that this particular student forgot to do what he had to do, and the animals escaped,” Quinn says. “They were last seen going down South Orange Avenue.”

The inanimate creche outside the chapel at Christmas now poses no escape hazards.

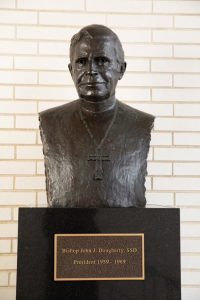

A Presidential Bust

At the top of the entry stairwell in the Bishop Dougherty University Center is a bust of the University president throughout the 1960s for whom the building is named. “It’s perfect; that’s him,” Monsignor Wister says of the likeness.

Wister was an undergraduate in the first years of Dougherty’s presidency, a product of the same Jersey City parish, Saint Aloysius. “When he gave talks here it was high drama. Everyone went because it was like a show. He’d come in with his flowing cape on, and he’d be flashing it up in the air, and he had this deep baritone voice. He was a delightful character, and you couldn’t help but like him. He knew that people teased him about being a ham.”

That voice was familiar to the audience of “The Catholic Hour,” the show — first on radio and then television — that Dougherty hosted in the 1950s, like his media counterpart Bishop Fulton J. Sheen.

“He was a transitional figure in a way because Seton Hall was kind of revolutionized in the 1960s,” Quinn says of Dougherty, who also served as auxiliary bishop of Newark while he was president. “It went from being basically all-male to coed; new buildings went up. It became more of a liberal arts university, and he presided over all of that.”

Among those new buildings was the one where his bust now stands watch — the student center

that was his idea, and that includes the Theatre-in-the-Round he suggested to accommodate his love of classical drama.

The Detour on the Green

Bishop Dougherty’s bust has a commanding view through the University Center’s tall atrium windows onto the Green around which the campus radiates. A curious pedestrian traffic pattern prevails there: As students cross the Green they veer slightly around the University seal that is inscribed in a granite circle at its center. The seal was installed more than three decades ago in one of the many reconfigurations of that central space where commencement was once held, and where a superstition quickly emerged: Step on the seal, and you won’t graduate. If you do — perhaps inadvertently these days while engrossed in texting — there is an antidote that can reverse the curse: Run to the pirate statute outside the Richie Regan Recreation and Athletic Center and touch its foot within 30 seconds of your transgression. Hazard Zet Forward, the seal commands, the school’s motto: “Whatever the peril, ever forward.” But please look both ways when crossing Seton Drive.

Bishop Dougherty’s bust has a commanding view through the University Center’s tall atrium windows onto the Green around which the campus radiates. A curious pedestrian traffic pattern prevails there: As students cross the Green they veer slightly around the University seal that is inscribed in a granite circle at its center. The seal was installed more than three decades ago in one of the many reconfigurations of that central space where commencement was once held, and where a superstition quickly emerged: Step on the seal, and you won’t graduate. If you do — perhaps inadvertently these days while engrossed in texting — there is an antidote that can reverse the curse: Run to the pirate statute outside the Richie Regan Recreation and Athletic Center and touch its foot within 30 seconds of your transgression. Hazard Zet Forward, the seal commands, the school’s motto: “Whatever the peril, ever forward.” But please look both ways when crossing Seton Drive.

The Marble Stone

Seton Hall moved from Madison to South Orange in 1860 when Bishop Bayley bought a portion of the Elphinstone estate: 60 acres and a large villa built of white marble, which originally housed the seminary.

“He had to have the [purchase] basically conveyed in secret so that it wasn’t known that a Catholic was buying it,” Quinn says. “There was a bit of anxiety among the local Protestants.”

But the villa burned to the ground in 1866, and a new seminary, now Presidents Hall, quickly rose in its place, with some pieces of the original marble repurposed in

its foundation.

“In wandering around the building, you can see they had a few stones from the original that they integrated into it,” Monsignor Wister says. If you approach the entrance and then, instead of climbing the stairs into the building, veer into the bushes on the left side and slip back toward the corner, you will see one. It’s easy to miss, but it’s there, beside a downspout and beneath a mossy brown stone, one of the last pieces from the first days of the school’s life.

Kevin Coyne is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

Please allow me to share a story about the Seton Hall College Bell.

The class of 1932 had thirty graduates half of whom became priests. One of those grads was my uncle Matt Cummings who paid for me to complete a four year degree 50 years later.

The Seton Hall bell was actively used them to wake the students for morning prayers. One day, Uncle Matt and his roommate conspired to paint the inside of the bell so as to deaden the sound when it rang in the morning. Naturally the authorities were outraged and went hunting for the culprit(s). They went door to door and when arriving at my uncle’s room discovered a spec of paint on his roommates shoe. Needless to say, the roommate spent the rest of the day cleaning paint off the bell.

In 1982 my aunt and uncle came to visit the campus just before graduation. The bell was then displayed out side and when Uncle Matt saw the bell he started laughing and told the story that his wife of many decades had never heard.

My uncle loved Seton Hall and was generous enough to pay my tuition for four years. Good bless him and Seton Hall.