To commemorate Immaculate Conception Seminary’s 150th anniversary, Monsignor Wister, an associate professor of Church history, embarked on a quest to write the definitive history of the institution. Over six years, he reviewed original correspondence between rectors and bishops, read journals, textbooks and newspapers, and pored over hundreds of photographs, consulting sources that had never before been used for scholarly purposes.

To commemorate Immaculate Conception Seminary’s 150th anniversary, Monsignor Wister, an associate professor of Church history, embarked on a quest to write the definitive history of the institution. Over six years, he reviewed original correspondence between rectors and bishops, read journals, textbooks and newspapers, and pored over hundreds of photographs, consulting sources that had never before been used for scholarly purposes.

To a traveler sailing on the Nile, gazing at the monuments of the pharaohs, 150 years might seem to be no more than a blink of an eye. Even in the history of a Church that measures time in centuries, a century and a half does not appear to be so long a time. In the life of the Church in the United States, it is quite a different matter.

Most of the seminaries established in the United States since the first in 1791 have disappeared. Simply to have survived is an accomplishment. To have prospered and thrived is an astounding feat.

The story of Immaculate Conception Seminary reflects the history of the United States and the history of the Catholic Church in this country. I do not know of any other seminary north of the Mason-Dixon Line that had a rector who was a veteran of the Army of the Confederate States of America. All seminaries have faced financial crisis, but what other seminary was on the brink of sale by its bishop not once or twice, but on three separate occasions?

Like all seminaries, it has alumni who became bishops. But it also is a seminary that has produced chaplain heroes who have received the Medal of Honor and a unique Congressional Medal of Valor in two twentieth-century wars.

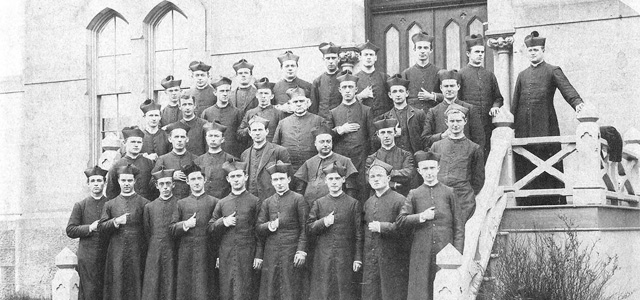

At one time or another, Immaculate Conception Seminary has been a school with a dozen or more seminarians within a small college, an enclosed monastery-like institution with more than 300 seminarians, and finally a seminary and school of theology educating seminarians and lay men and women on the campus of a major university.

In each of these incarnations, it has maintained its central mission of training men for the priesthood of the Catholic Church as it has adapted to the needs of the Church and the realities of the times.

From 1808 until 1853, Catholic New Jersey had been divided into two parts, the eastern section a part of the diocese of New York, the western a part of the diocese of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. By decree of Pope Pius IX, it had a new integrity as a single diocese encompassing the entire state.

The best estimates at the time count approximately 30,000 Catholics in the new see. Most were concentrated in the northeastern portion of the state, in the cities of Newark and Elizabeth and their environs, and in nearby Hudson County. The remainder were scattered from the Delaware Water Gap to Cape May.

To govern this new missionary diocese, the pope chose a young American of upper-class background, James Roosevelt Bayley. Born in 1814, he first studied medicine but found his calling in the priesthood of the Episcopal Church, and was ordained in 1840, serving as rector of St. Andrew’s Church in Harlem. Like a number of his confreres, probably influenced by the Oxford Movement, Bayley harbored doubts about Anglican claims, and resigned his rectorate the next year.

He traveled to Rome and, in spite of opposition from his family, he entered the Catholic Church in 1842. In doing so, he was following in the footsteps of his father’s half-sister, Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton. He was ordained a priest in 1844, and served as vice president of St. John’s College, Fordham; pastor in Staten Island, New York; and secretary to Bishop John Hughes. On October 30, 1853, he was consecrated the first bishop of Newark by Archbishop Gaetano Bedini in the old New York cathedral on Mott Street.

Two days later, the 39-year-old bishop crossed the Hudson River, debarked on the shores of his new diocese, and took the train to Newark. The train chugged into Newark where “thousands and thousands” welcomed him and, led by three brass bands, escorted him in an impressive procession to St. Patrick’s Church, which had been designated the cathedral.

After the ceremony, Bayley was honored at a gala banquet provided by the rector of the cathedral, Reverend Bernard J. McQuaid, who sold his horse and carriage to meet the expense. Many of the clergy had been concerned that such public Catholic demonstrations and open display might arouse Nativist feelings, and had complained to Bayley about McQuaid’s plans. To Bayley’s queries, McQuaid responded: “You are not bishop yet, and if trouble comes, then suspend me after you have taken possession of your cathedral.”

McQuaid was a familiar face to Bayley. The bishop had known him as a student during his time as vice president of St. John’s College, Fordham. McQuaid, born in 1823, had a difficult, if not traumatic, childhood. His mother died when he was only four years old and his father remarried, only to die in an accident before McQuaid was seven. His “life with his stepmother had become such that … even to the day of his death, [he] could not shake off the bitter memories of the woman who abused him terribly in his childhood.” Fortunately, he was sent to the Prince Street Orphanage of the Sisters of Charity in New York, where the sisters provided his early education.

McQuaid then attended Chambly College near Montreal before going on to St. Joseph’s Seminary at Fordham. Frail as a youth, he suffered a severe hemorrhage at Fordham but recovered after Father Bayley applied an “old-fashioned remedy.” Many years later, he referred to his early frailty, remarking that “sixty-three years ago friends expected to put me under the sod.”

He was ordained in 1848, five years before the establishment of the diocese of Newark. Assigned to Madison, New Jersey, he thereby became a priest of the new diocese and, five weeks before Bayley’s installation, was named rector of the newly designated Cathedral of St. Patrick in Newark.

Bishop Bayley quickly began to learn about the diocese and to assess its needs. He discovered that there were some 30,000 to 40,000 Catholics across the 7,400 square miles of New Jersey. Half of New Jersey’s foreign-born population was in Hudson and Essex Counties.

The first church, St. John’s, had been established in Trenton in 1814, and the first in Newark, also St. John’s, in 1828. The number had grown to 33 churches and missions in 1853. Appealing for funds in June 1854, Bayley described the situation in a letter to the Society for the Propagation of the Faith in Lyons.

… the number of priests is not in proportion to the faithful; the diocese can count only on thirty-three clergymen to meet all its wants and demands. And what is most regrettable is the state of New Jersey, having been regarded up to the present as an accessory rather than an integral and a permanent part of the dioceses of New York and Philadelphia, does not possess a single institution of learning or religion, so necessary to the establishment of religion.

Catholic education at all levels would be the cornerstone of Bayley’s efforts during his episcopate in Newark. He moved swiftly not only to establish parochial schools, but, in spite of financial difficulties, to found a college and a seminary. One of the reasons for this ambitious undertaking was to improve the cultural level of Catholics in order to help eliminate prejudice, which the bishop knew well from his own Protestant background.

Many of our Catholic immigrants have made fortunes, and if their children can be taught that in holding to their faith they can stand on the same level with Protestants, they will be able little by little to remove the prejudices which hinder the enemies of the Church from examining the truth of our holy religion.

Bayley was continually concerned about the shortage of priests. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s he sought to obtain priests from abroad, chiefly from Ireland. His successes were few. Many seminarians, whom he sponsored at great expense for a poor diocese, left before ordination. Some proved to be problems after ordination. Others asked to leave for another diocese after just a few years in Newark. Years later, he wrote that “for the most part, the only way by which we can hope to obtain [priests] is by taking those of our youth who give evidence of a vocation … and educating them ourselves.”

In 1855, Bayley purchased the property belonging to the Young Ladies’ Academy conducted by Madame Chegary at Madison, New Jersey. He named the new institution “Seton Hall” in honor of his aunt, Mother Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton. This institution was to have a twofold purpose: the education of young Catholic laymen and the training of future priests.

Charged with establishing the institution was 33-year-old Father Bernard McQuaid, still rector of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Newark. While the gentle and mild-mannered Bayley was the visionary father of Seton Hall and Immaculate Conception Seminary, McQuaid was the practical and hard-driving force behind their creation and their survival in the early years. McQuaid was a man who “knew no timidity.”

According to Joseph M. Flynn, in his 1904 history of The Catholic Church in New Jersey, “There is every reason to believe that success would not have crowned Bishop Bayley’s efforts for the establishment and continuation of the college, has it not been for the indomitable energy and zeal of Father McQuaid.” The dauntless and indefatigable McQuaid hoped to have “30 to 40 students” when the college opened on September 1, 1856, but only five answered the first roll call. Among them was Leo G. Thebaud, who was ordained a priest eleven years later. By the end of September, 20 more had registered.