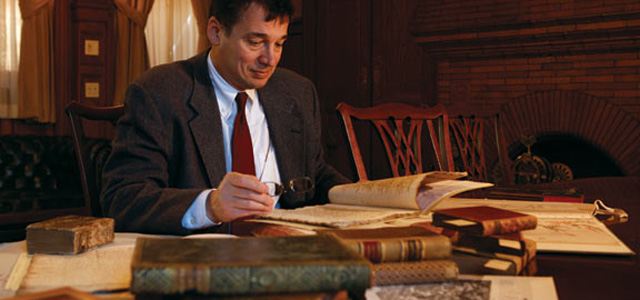

A tiny notation in a long-forgotten letter translates into a major find for historian William Connell.

William Connell didn’t set out to rewrite history. He just wanted the facts. His search began with a footnote, a passing reference to a letter from the Florentine Chancery in 1513 that appeared to have a connection to Niccolò Machiavelli. After following the trail across the Atlantic, Connell believes he has uncovered a letter whose true intent remained hidden for 500 years — a letter that likely played a key role in the writing of Machiavelli’s The Prince.

Early on a Saturday morning more than four years ago, Connell, a history professor and the Joseph M. and Geraldine C. La Motta Chair in Italian Studies, boarded a ferry leaving from Stresa, Italy. He was bound for the popular tourist destination of Isola Bella where, in the 17th century, the Borromeo family built a grand palace. Over the past four centuries, this noble family amassed a storied collection of historical documents — including the letter referenced in the footnote read by Connell.

As tourists walked the island’s grounds and remarked on the classic paintings and furniture within the palace walls, Connell, 49, entered an unadorned study with the keeper of the Borromeo family records. The archivist brought forth original correspondence from a massive storeroom lined with wood and steel shelves.

In a room big enough for only a few people, Connell set to work examining a seemingly innocuous letter addressed to Francesco Vettori, the ambassador to the Holy See, with the postscript “N. Mach. L.”

“There wasn’t the immediate shock of discovery,” says Connell of his find. “It was a puzzle that needed to be unfolded, and that puzzle is, why is the name Machiavelli at the bottom of that letter?”

Even though the letter came from the chancery where Machiavelli was once employed and was written to his patron Vettori, it seemed impossible that Machiavelli could have written the missive himself. The letter was dated Nov. 12, 1513, almost a year after Machiavelli was forced to leave the chancery. A conflict with the Medici family, who returned to power in 1512, had led to a one-year ban on Machiavelli’s travel, a sentence that expired two days before the letter was written.

Cracking the code

Connell believes the letter was written not by Machiavelli, but was in fact a cryptic message about him from an unknown scribe in the government of Florence to a patron, sympathetic to Machiavelli. The letter, essentially saying that nothing is happening in Florence, has a postscript that was an ingenious way of telling Vettori that Machiavelli was free to travel.

The scribe, Connell says, had subtly changed the name of Niccolò Michelozzi, Machiavelli’s successor in the chancery, who was referenced in letters as “N. Mich. L.,” to “N. Mach. L.,” for Machiavelli.

“All it comes down to is the difference between an “A” and an “I.” And yet, even if the coded message was discovered, there is a little degree of deniability,” says Connell, impressed with the subterfuge. The notation could easily be dismissed as an innocent error.

The letter didn’t arouse suspicion, and it arrived in Rome on Nov. 18. Five days later, Vettori penned a missive to Machiavelli, inviting his friend to come for an extended visit.

“This is part of the chain reaction that leads Machiavelli to write his famous letter — probably the most famous private letter ever written — describing what he was working on,” says Connell, “the work that would become The Prince. This was Machiavelli’s letter to Vettori dated Dec. 10, in which Macchiavelli announced he was writing a book about princes that he would dedicate to the Medicis.”

The next chapter

Historians don’t jump to conclusions — they gather evidence in order to place events within a context. After his trip to Isola Bella, Connell journeyed to Florence to view another collection of letters that had originally included the Borromeo letter. Using scans and the information he’d gathered from the Borromeo family records and comparing them to the collection in Florence, Connell was able to authenticate the document: the signature and date had not been altered.

“I would have been perfectly happy to say the letter was fake and to have discovered that,” says Connell.

Machiavelli has been a constant throughout Connell’s academic life, beginning with his doctoral dissertation at the University of California, Berkeley, which sought to interpret historical documents from the Florentine territory that Machiavelli helped to control. Nearly two decades of work led Connell to publish an updated translation of The Prince in 2005.

“A lot of people who work with Machiavelli are looking from a political perspective of what is right or wrong.

I come from the historian’s perspective of trying to determine what actually happened,” says Connell.

Machiavelli once wrote, “one change always leaves the way open for the establishment of others.” He might have been envisioning the history professor’s dogged pursuit of the chain of events that led to The Prince being written.

Connell is attempting to sort out the last piece of the chancery letter puzzle: the identity of the scribe who wrote it. He has eliminated five of the 10 scribes working in the chancery at the time, and he has uncovered several more documents written in the same hand.

Once he finds that answer, Connell will publish his findings in a journal and move on to uncover whatever mysteries await him on his next project: a search through the archives of another family from the Italian Renaissance.

“This is what historians try to do,” says Connell. “You bring new evidence to bear and retell the story in an interesting manner.”

Jonathan Bender is a freelance writer based in Kansas City, Mo.

The image above is courtesy of the Archive and the Princes Borromeo-Astese. Special thanks to the Monsignor William Noé Field Archives and Special Collections Center and Alan Delozier for sharing some medieval manuscripts with us.