Does Wikipedia Tell the Truth?

Nathaniel Knight, Associate Professor and Chair, Department of History, Seton Hall University.

Those of us who have been teaching for a while will no doubt remember the moment when we first learned of Wikipedia. In my case, it was a student in a historical methods class who proclaimed the news—a new on-line encyclopedia that anyone can amend or edit. Like many, I first reacted with incredulity. So this is what the world has come to, I thought. Anyone can be an expert and broadcast delusions to the world at large via the internet. I told my students that under no circumstance did I want to see them consulting such a dubious source of knowledge.

It’s always nice to be proven wrong. At some point not too long after I delivered that stern injunction to my students, I found that I myself was relying on Wikipedia. It started turning up when I searched the internet and as I followed the links I found pages that allowed me to orient myself almost instantaneously on topics about which I knew very little. Whether it was a band I had just heard on the radio, or some obscure piece of historical minutia, there was enough seemingly accurate information on Wikipedia to slake my curiosity and provide leads for further inquiry. Over the years I’ve come to see it as an indispensable resource, a vast compendium of knowledge on every imaginable topic. Now, far from castigating my students who use Wikipedia, I encourage them to consult it—with the proviso, of course, that it should be a starting point for research, not a final destination.

Wikipedia’s strength lies in its fortuitous balance between chaos and control—a continual back and forth between anonymous contributors and a small army of volunteer editors who, lacking detailed content knowledge themselves, monitor and regulate the editing process in accordance with a detailed and clearly articulated set of protocols. Not long ago, however, a situation arose that called into question Wikipedia’s editing procedures and in the process cast a revealing light on the expansion of knowledge and the nature of historical truth.

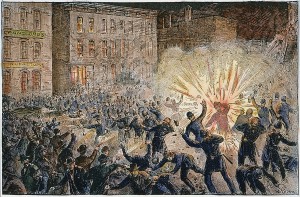

Dr. Timothy Messer-Kruse of Bowling Green University is among the country’s foremost experts on the Haymarket riot and trial of 1886, one of the iconic events of American labor history. According to the commonly accepted narrative enshrined in textbooks for almost a century, on May 4th at Haymarket Square in Chicago, police attacked a peaceful gathering of striking workers fighting for the eight hour day. In the pandemonium that followed, a bomb went off killing several officers. The police retaliated with live ammunition leaving four dead and scores wounded. In the aftermath, the authorities choose to place full responsibility on the radicals. A group of Anarchist leaders were arrested, subjected to a sham trial, and several were hanged despite the fact that no evidence was presented linking them to the crime. The incident had a galvanizing effect on American society, leading in the short run to the first great “red scare” in American history, but remembered in the long term as one of the greatest miscarriages of American justice.

Dr. Messer-Kruse has been studying the Haymarket events for at least a decade, and out of his engagement with the sources a very different version of events has arisen, one that directly contradicts the accepted narrative. The crowd of striking workers, Messer-Kruse suggests, may not have been so peaceful after all. A number were armed and eyewitnesses reported gunshots emanating from the crowd as well as from police lines. The trial too was hardly the travesty it is generally made out to be. Over the course of 6 weeks, over 100 witnesses testified presenting evidence of violent conspiratorial activity in which anarchist leaders participated. Among the witnesses was a chemist who undertook a path-breaking forensic analysis that linked the bomb thrown at the demonstration with bomb-making material found at the home of one of the defendants. Whether all of the convictions were justified is an open question, but blame for the outcome can at least in part be placed on the defense attorneys who opted for political grandstanding rather than mounting an effective defense for their clients.

Having achieved this new understanding of the Haymarket affair, Dr. Messer-Kruse thought he might perform a useful service by correcting some of the misinformation contained in the corresponding Wikipedia article. But no sooner did he start to change some of the more obvious inaccuracies, when he found himself firmly rebuffed. Within minutes his edits were reversed and the text reverted back to its initial state. Wikipedia editors explained their actions by alluding to the lack of proper citations. This came as a surprise to Mellor-Kruse who had in fact provided citations via his personal blog back to the trial transcript and other primary sources. But primary sources, it turned out, are not considered authoritative on Wikipedia. What was needed were citations to secondary works—accounts by established historians, properly vetted and published in reputable venues, in short, precisely the works Messer-Kruse was challenging.

Even the appearance of Dr. Messer-Kruse’s own monograph two years after his first encounter with Wikipedia did not substantially improve matters. Although his work was impeccably documented and published with a reputable academic press, it still fell afoul of the Wikipedia doctrine of “undue weight.” What this means is that a minority view of a particular topic should not be undue weight when it goes against what appears to the view of a majority of scholars. One editor explained that if 99 historians claimed the sky was green in 1880 and one said it was blue, blue skies would be acknowledged only as a minority interpretation. Verifiable assertion is the standard to which Wikipedia aspires—not truth itself. It was only when Dr. Messer-Kruse published an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education recounting his experience that a serious discussion began on the Wikipedia talk pages and changes were made.

It is easy to understand Dr. Messer-Kruse’s frustration. Historians engaged in detailed research with primary sources will inevitably find facts and assertions repeated time after time in the secondary literature that turn out to be inaccurate if not downright wrong. All it takes is a single slip—a source not checked, an assumption not verified, a text misread—for inaccuracies to become enshrined in an authoritative work and repeated for decades to come. It is precisely for this reason that historians insist on returning to the sources, even for topics with a well-established historiography. Only by immersing themselves in the original materials and piecing together a narrative from the ground up, can historians cleanse the record of its accumulated errors and arrive at new interpretations. This, it would appear, is exactly what Dr. Messer-Kruse has done, and he understandably feels that his narrative should take precedence.

Readers may be surprised, therefore, to find that my sympathies in the controversy lie not so much with Dr. Messer-Kruse, as with Wikipedia. It is certainly tempting for a scholar to emerge from the archives guns blazing and to charge straight for Wikipedia, but this may not be the most effective strategy. Like any encyclopedia, Wikipedia is largely a repository of conventional wisdom. Its purpose is to acquaint non-specialists with the closest approximation to a consensus view. There are good reasons why Wikipedia editors would look with skepticism on a single scholar, however well-credentialed, who attempts to overturn an established historical narrative. Perhaps Dr. Messer-Kruse, is right about the Haymarket affair, but he stands against a cluster of well-known authorities who no doubt also examined primary sources in formulating their views. So it becomes a matter of judgment, and the question inevitably arises—whose? Should the historical consensus be decided by a random assortment of volunteer editors at Wikipedia with no specialized training whatsoever? Or, perhaps, the matter should be left to the historians themselves.

The formation of a historical consensus, to be sure, is not a rapid process, but contrary to Messer-Kruse’s assertion in the conclusion to his Chronicle article, it is a matter of years, not decades. Within 3-5 years of the appearance of an important monograph, generally, a range of scholarly reviews will have been published, citations will have started to crop up, and any new work on the topic that does not engage the monograph will be considered deficient. Even if a clear consensus has not emerged, there will be enough of a response to allow an informed observer to determine whether an interpretation remains controversial and whether a work has been acknowledged as an authoritative source. This is the point at which editors of Wikipedia can safely integrate a new historical interpretation into its articles.

Of course, it is difficult for an author to have to wait several years for what may seem like blatant factual errors on Wikipedia to be corrected. But imagine the alternative. Remove the requirement that changes reflect a consensus of expert opinion and the result would be a field day for holocaust deniers, conspiracy theorists, crackpots, mystics and revisionists of all shapes and kinds. In the process Wikipedia would lose the very features that have brought it success—its reliability and impartiality. Dr. Messer-Kruse feels his experience reflects a lack of deference to contributors with academic credentials. It seems to me, however, that the episode only highlights the critical importance of the academic community to an enterprise like Wikipedia. The facts of history are rarely as clear and straightforward as they appear at a distance. Historical truth exists without a doubt, but it is only accessible through sources which more often than not present an incomplete, opaque and even misleading picture. Lacking the full story, the historian’s task is to arrive as close a reconstruction of truth as is humanly possible given the available resources. To do this requires specialized skills, breath of knowledge and sound judgment honed through years of engagement with the past. The firmest verification of a historian’s reconstruction of the past lies in the informed assent of his or her peers. It is to Wikipedia’s credit that it has not tried to usurp this role, but rather uses the model of academic consensus as its guiding principle. The verdict of history may not always be prompt, but it is well worth the wait.

Postscript: This piece was originally written in 2012 when the controversy first erupted and was published on the now-defunct Franklin’s Opus blog. Since that time, the Wikipedia article on the Haymarket affair appears to have been further refined with additional information and citations. Timothy Messor-Kruse’s views are acknowledged as one of several interpretations and his book is cited in a few places in support of factual assertions. For the most part, however, the article continues to reflect the traditional narrative regarding the Haymarket riot and its aftermath. For now, it would seem, the consensus stands.

Readings

“The Haymarket Affair” Wikipedia: the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haymarket_affair Accessed October 17, 2015.

Timothy Messer-Kruse, The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists: Terrorism and Justice in the Gilded Age. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Timothy Messer-Kruse, “The Undue Weight of Truth on Wikipedia.” http://chronicle.com/article/The-Undue-Weight-of-Truth-on/130704/. Accessed October 17, 2015.

Wikipedia can be easily manipulated these days and the more bad actors there are online, the worse its going to get.