Playthings from the Past

By Sara Fieldston, Assistant Professor of History, Seton Hall University

As the new year begins, children across America are enjoying their holiday loot. Ever wonder what kinds of playthings kids from bygone times might have expected to find under their trees? Here is a roundup of interesting historical toys that shed light on the American past.

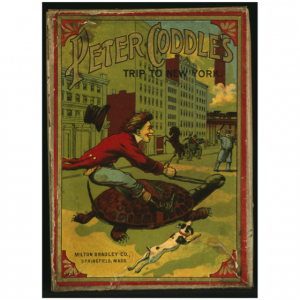

Peter Coddle’s Trip to New York was a popular turn-of-the-century game (though versions of the game appeared as early as 1858). Much like modern-day Mad Libs, the game featured a story with multiple nouns missing; players pulled cards from a deck and read the words printed on them to fill in the blanks, creating a silly tale in the process. “The curious and contrary nature of the articles, for the uses to which they are assigned in the story, cannot fail to excite merriment and laughter,” the game’s instructions promise.

Peter Coddle’s Trip to New York was a popular turn-of-the-century game (though versions of the game appeared as early as 1858). Much like modern-day Mad Libs, the game featured a story with multiple nouns missing; players pulled cards from a deck and read the words printed on them to fill in the blanks, creating a silly tale in the process. “The curious and contrary nature of the articles, for the uses to which they are assigned in the story, cannot fail to excite merriment and laughter,” the game’s instructions promise.

In the story that accompanies the game, Peter Coddle is a naïve rube from the countryside who decides to take his first trip to the big city. He boards a train that carries him from his small town into the heart of the city, where he is greeted by a sensory overload: the rattle of the streetcars, the smell of smoke, the dazzle of the wares in the shop windows. With the aid of the fill-in-the-blank cards, Coddle attests: “geewhittaker, I never did see the best of such sights before! Right in front of me was an elderly porcupine running right through a basin of turtle soup and over on one side of the street was an Egyptian mummy selling a procession of cockroaches to a city missionary and then there was an ivory-headed cane running on two rails in the middle of the street and all the queerest sights anyone could imagine.”

There were several versions of the Peter Coddle game produced by different game companies, and each gave Coddle’s story a particular twist. In the tamest version of the story, Coddle loses his friend in the crowd after a cry of “fire!” causes the audience in a theater to panic. In the most extreme version of the tale, the unfortunate Coddle is slipped a drug by a smooth-talking con-artist who steals his clothing and all his money. His trip culminates with an arrest for appearing drunk. “I’ve lost all my money and new clothes, and got nothing in exchange but a lame porpoise and a pair of old pantaloons,” Coddle laments (with the aid, of course, of the fill-in-the-blank cards).

Peter Coddle’s Trip to New York provided children with a source of silly fun, but it also carried larger cultural messages. In following Coddle from countryside to city, the game traced a route trod by many individuals during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Fueled both by migrants from small towns and by immigration from overseas, cities grew tremendously in the years following the Civil War. New York City’s population increased from about half a million in 1850 to over 1.5 million by 1890. Urban tourism increased, too, as Americans began to view city attractions—restaurants, shops, theaters—as equally worthy of a visit as the natural sites, such as Niagara Falls, that had previously drawn the majority of tourists. An expanding network of railroads swept people across the country more rapidly than ever.

Peter Coddle’s trip, then, was one that many young game players might expect to make during their lifetimes. By following Coddle into the city and describing his mishaps, the game taught children how to be savvy urban visitors. While young people were unlikely to come across a pickled whale or a small-mouthed crocodile on their visit to the big city (to use two fill-in-the-blank words), there was a likelihood of encountering rattling streetcars, chaotic crowds, and even con-men eager to swindle them out of hard-earned money. In introducing children to both the dangers and the pleasures of urban life, Peter Coddle’s Trip to New York was a primer that helped young people make sense of the rapidly-urbanizing nation.

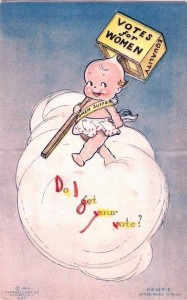

Chubby-cheeked, wide-eyed, and smiling, the kewpie doll remains a familiar icon today. Named for the cupids they resembled, kewpie dolls were first produced in 1912. Kewpies enjoyed phenomenal popularity: before the birth of Mickey Mouse in 1928, the kewpie held the distinction of being the most famous character in America.

Kewpies were the brainchild of Rose O’Neill, an illustrator who introduced them in a comic strip in the recently-launched women’s magazine The Ladies’ Home Journal in 1909. O’Neill had begun her career as an illustrator at an early age. As a thirteen-year-old, a newspaper sponsoring a children’s drawing contest was so impressed with her submission that O’Neill was asked to prove that she had actually produced the illustration. A quintessential New Woman, O’Neill bobbed her hair, married and divorced twice, and was a vocal proponent of women’s suffrage. Her kewpie characters embodied her values. The cherubic characters—gendered male in the cartoons but with a purposefully androgynous appearance—carried placards in support of women’s suffrage. While O’Neill eschewed constricting Victorian dresses, kewpies rarely wore any clothing at all.

Kewpies were the brainchild of Rose O’Neill, an illustrator who introduced them in a comic strip in the recently-launched women’s magazine The Ladies’ Home Journal in 1909. O’Neill had begun her career as an illustrator at an early age. As a thirteen-year-old, a newspaper sponsoring a children’s drawing contest was so impressed with her submission that O’Neill was asked to prove that she had actually produced the illustration. A quintessential New Woman, O’Neill bobbed her hair, married and divorced twice, and was a vocal proponent of women’s suffrage. Her kewpie characters embodied her values. The cherubic characters—gendered male in the cartoons but with a purposefully androgynous appearance—carried placards in support of women’s suffrage. While O’Neill eschewed constricting Victorian dresses, kewpies rarely wore any clothing at all.

When an American businessman approached O’Neill about creating a prototype for a kewpie doll, she labored to produce a figure that resembled her cartoons. Once she received the samples from the German factory where the doll would be produced, however, O’Neill was horrified. The dolls had, she complained, the “shoulders of a pugilist, tummy of a drunken Silenus, the face of an infant fiend—the sidelong eyes and the smile, a diabolical leer!” O’Neill forced the factory to destroy the mold, and she worked with another dollmaker to craft a kewpie more fitting with her vision. The final product, while no longer the “infant fiend” that had horrified O’Neill, still departed from the original articulation of the kewpie as presented in her comic strip. Instead of an androgynous male, the kewpie doll was now marketed as female. Instead of marching proudly with suffrage placards, the dolls now cast bashful smiles. The kewpies’ popularity soared, but the dolls’ bisque bodies contained few traces of O’Neill’s original radical vision.[1]

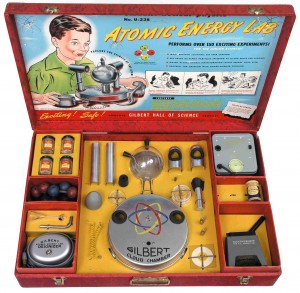

The United States dropped the first atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945. In the aftermath of the attacks, observers noted a plethora of reactions: horror at the magnitude of the destruction; elation over the end of the war; anxiety concerning the future of civilization; fascination with the mechanics of nuclear energy. It was this latter reaction that gave rise to a new phenomenon in children’s playthings—atomic toys.

The years immediately following the Second World War saw the proliferation of toys that featured atomic energy. Kix Cereal boxes offered youngsters the opportunity to send away for a “Kix Atomic ‘Bomb’ Ring,” promising the opportunity to “see real atoms split to smithereens.” The ring contained polonium alpha particles that hit a zinc sulfide screen, producing small flashes of light. Aspiring scientists could perform experiments using Gilbert’s U-238 Atomic Energy Lab, a kit that contained several samples of radioactive materials and a “cloud chamber” for watching the materials react. Gilbert also sold a Geiger counter so children could search for uranium deposits themselves. To encourage young would-be prospectors, Gilbert noted that the U.S. government offered a $10,000 reward to anyone would discovered substantial new sources of uranium.

Anxiety over the inability to control atomic energy once it had been unleashed inspired characters such as Godzilla, the famous monster with radioactive breath. In suggesting that the power of atoms could be contained in a small vial atop a child’s ring finger, atomic toy manufacturers presented nuclear energy as safe and manageable. “Atomic materials in Atom Chamber are harmless,” Kix Cereal promised. Gilbert described its Geiger counter as “Safe! Exciting! Instructive!”

The atomic toys also subtly rallied support for the United States’ military and foreign policy objectives, which centered on amassing huge stockpiles of atomic weapons in an effort to counter the Soviet threat. In 1952, shortly after Gilbert’s Atomic Energy Lab debuted, the United States successfully exploded a hydrogen bomb, a weapon about a thousand times more powerful than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By the 1980s, the Gilbert Geiger counters were gathering dust, and the United States possessed over 20,000 nuclear weapons. The half-life of the country’s arsenal would prove to be much longer than that of the atomic toys.

[1] For more information on Rose O’Neill and the kewpie dolls, see Miriam Formanek-Brunell, Made to Play House: Dolls and the Commercialization of American Girlhood, 1830-1930 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 117-134.

love to read this amazing post