Remembering Easter 1916

by Dr. Dermot Quinn, Professor of History

Seton Hall University

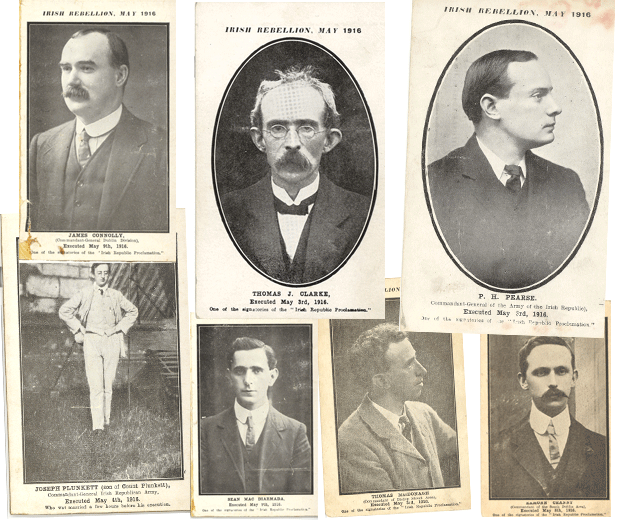

I was in Madrid recently giving a talk on G.K. Chesterton when I came across a sign which said more than it intended. About three hundred yards from the Prado, above a place called St. James’s Gate, it read simply: “Irish Pub: Practice Your English Here.” So much history in six words. (Add another three words – St. James’s Gate – and you get more history. Saint James’s Gate in Dublin, home of Guinness, is where pilgrims began their walk to Santiago de Compostela in the middle ages.) Was it for this that Pearse, Connolly, Clarke, MacDiarmada, Ceannt, MacDonagh, and Plunkett gave their lives in 1916? The teetotaler Patrick Pearse for whom nothing mattered more than the Irish language carrying with it, he said, “Irish music, Irish art, Irish dancing, Irish games and customs, Irish industries, [and] Irish politics.” The Marxist James Connolly, another teetotaler, who demanded for Ireland a socialist republic because without one “England would still rule…She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and industrial institutions she has planted in this country”? The Anglophobic Tom Clarke, his loathing for England well-honed in a prison cell for fifteen years, who thought it “grand” whenever England got a “slating”? The easy-going Eamonn Ceannt, who insisted, good Gaelic Leaguer that he was, that the shamrock was not for drowning but to be worn proudly and “unsullied”? The charming and amiable Sean MacDiarmada, whose party-piece was to recite all seventy lines of Father Michael Mullin’s poem, “The Celtic Tongue”: “Sons of Erin! Vain your efforts – vain your prayers for freedom’s crown/Whilst you crave it in the language of the foe that clove it down.” Perhaps Thomas MacDonagh, poet, academic, and whiskey-drinker, might have forced a smile at the paradox of an English-speaking Irish pub in Spain. “He is more a European,” recalled his student Desmond Ryan, “and cannot get to the heart of Gaeldom so profoundly as Pearse. There are moments when the native speakers and the Gaeltacht bore him stiff, and he returns to Elizabethan poetry and France and Greece and Rome.” As for Joseph Plunkett, cosmopolitan, literary, gifted in all sorts of ways, he would surely have seen the sign for the conceit that it was, an Irish bull in a Spanish bullring. His literary hero, in fact, was G.K. Chesterton and so we may presume in him a taste for paradox. “Now Gilbert you know you’re our man/The only one equal to seven/Tho’ you stand on the earth yet you span/With your hands the four quarters of Heaven.”[1] Irish history would have taken a different turn if the enormous Chesterton – the one equal to seven – had issued the orders that Easter Monday. Instead, Pearse and the rest of them signed the proclamation and, with it, their death warrants.

I was in Madrid recently giving a talk on G.K. Chesterton when I came across a sign which said more than it intended. About three hundred yards from the Prado, above a place called St. James’s Gate, it read simply: “Irish Pub: Practice Your English Here.” So much history in six words. (Add another three words – St. James’s Gate – and you get more history. Saint James’s Gate in Dublin, home of Guinness, is where pilgrims began their walk to Santiago de Compostela in the middle ages.) Was it for this that Pearse, Connolly, Clarke, MacDiarmada, Ceannt, MacDonagh, and Plunkett gave their lives in 1916? The teetotaler Patrick Pearse for whom nothing mattered more than the Irish language carrying with it, he said, “Irish music, Irish art, Irish dancing, Irish games and customs, Irish industries, [and] Irish politics.” The Marxist James Connolly, another teetotaler, who demanded for Ireland a socialist republic because without one “England would still rule…She would rule you through her capitalists, through her landlords, through her financiers, through the whole array of commercial and industrial institutions she has planted in this country”? The Anglophobic Tom Clarke, his loathing for England well-honed in a prison cell for fifteen years, who thought it “grand” whenever England got a “slating”? The easy-going Eamonn Ceannt, who insisted, good Gaelic Leaguer that he was, that the shamrock was not for drowning but to be worn proudly and “unsullied”? The charming and amiable Sean MacDiarmada, whose party-piece was to recite all seventy lines of Father Michael Mullin’s poem, “The Celtic Tongue”: “Sons of Erin! Vain your efforts – vain your prayers for freedom’s crown/Whilst you crave it in the language of the foe that clove it down.” Perhaps Thomas MacDonagh, poet, academic, and whiskey-drinker, might have forced a smile at the paradox of an English-speaking Irish pub in Spain. “He is more a European,” recalled his student Desmond Ryan, “and cannot get to the heart of Gaeldom so profoundly as Pearse. There are moments when the native speakers and the Gaeltacht bore him stiff, and he returns to Elizabethan poetry and France and Greece and Rome.” As for Joseph Plunkett, cosmopolitan, literary, gifted in all sorts of ways, he would surely have seen the sign for the conceit that it was, an Irish bull in a Spanish bullring. His literary hero, in fact, was G.K. Chesterton and so we may presume in him a taste for paradox. “Now Gilbert you know you’re our man/The only one equal to seven/Tho’ you stand on the earth yet you span/With your hands the four quarters of Heaven.”[1] Irish history would have taken a different turn if the enormous Chesterton – the one equal to seven – had issued the orders that Easter Monday. Instead, Pearse and the rest of them signed the proclamation and, with it, their death warrants.

Paradox is at the core of the rising. A generation ago, Ruth Dudley Edwards called it a “triumph of failure,” a political and cultural success achieved on the back of a military and logistical disaster. That is not simply a clever line: it also captures the unexpectedness of a symbolic victory made possible not by British malevolence (which the rebels took for granted) but by British stupidity (which they did not). (Only Pearse wished for martyrdom although Plunkett, who was dying already, also spoke of his soul’s “divinest flame” seeking to die. The rest of them would rather have lived.) That aside, reactions to the rising have varied significantly since its fiftieth anniversary (not least, historiographically, by the restoration to the picture of women as well as men). There used to be a choice between “reverence for the Rising or scathing skepticism”, Fintan O’Toole wrote in The Irish Times recently. Now it is possible to hold both views.[2] Certainly the reverence has worn off. Too much has happened in the interim – too much blood-letting in the north of Ireland, too much sacred violence, too much research and revisionism, too much postmodern irony – to allow the haloes of Pearse, Connolly et al. to go unadjusted. Celebration has given way to commemoration, to contemplation, even contrition. (Of course, the last of these is nothing new. “Did that play of mine/Send out some men the English shot?” asked Yeats in 1938, characteristically fretting about the moral power of poetry by writing a poem. The answer to his question, by the way, is: almost certainly not.) Yet a centenary does seem to call for some sort of collective reaffirmation of an event that, one way or another, determined the next one hundred years of Irish history. Even a commentator as usually ironic as Declan Kiberd has spoken approvingly of the “nationwide cultural celebration” that took place in Ireland this year – “concerts, plays, poetry readings, energetic debate, often in the thoroughfares.” After the years of the Celtic Tiger, “in which everything from public transport to consciousness itself seems to have been privatized, the community was learning once again how to use public space and reclaim the streets. After the even more recent years of austerity, the people were simply happy to have something to celebrate.”[3] Using public space and reclaiming the streets? In a more innocent age, de Valera called it “comely maidens dancing at the crossroads.” Skepticism has given way to delight.

To be sure, other acts of remembrance have taken place this year, more painful because less practiced. 1916 was also the year of the Somme. More Irishmen, by many tens of thousands, were prepared to fight for the Empire than against it, my grandfather, a young Catholic from Donegal, being one of them. The usual explanations for this willingness to fight – that they were following instructions from Redmond, that they wanted to be with their friends, that they were deluded by false consciousness – seem too neat – the kind of explanations historians give – and too condescending – denying agency to those who, with their lives at risk, had every reason to exercise it. Few of them achieved the eloquence of a Tom Kettle who went to his death, he said, defending the “secret scripture of the poor” but their lives are reminders to us that there were different ways of being Irish in 1916. Pearse and his colleagues seemed to think there was only one.

The existence of those other Irelands is why the centenary may give us pause. The men of 1916 were teetotalers in another sense, having what historians these days like to call a “totalizing” view of Irish history, a narrative so sweeping as to sweep all other stories aside. They drew their legitimacy not from the inconveniently alive – those who might contradict them, those who might disagree, those whose interests did not align with theirs – but from the conveniently dead – those who represented “the old tradition of nationhood,” those who represented the unextinguished right of “every generation”, those who had risen six times in three hundred years to achieve that Irish freedom that they now proclaimed to exist. The past was invoked as a sanction and a prayer: “In the name of God and of the dead generations”; in Ireland’s “supreme hour” “under the protection of the Most High God” Ireland’s “freedom,” “welfare” and “exaltation” would be assured. They were thinly disguised theologians believing in a secularized version of divine providence, Ireland to achieve her freedom because such – despite the obscurities of history – was her destiny. It was as if Hegel was a member of the Gaelic League. The irony is that the men of 1916 promised freedom but were themselves in thrall to a kind of thanatological mysticism, the very names of the dead, Tone, Emmet, Mitchel, an incantation and an assurance to them.

In fact, their most obvious inspiration was not Tone or Emmett or Mitchel but Rousseau. The Easter Proclamation spoke of the “people of Ireland” or “the Irish people” or the “whole nation” as if the people of Ireland would recognize themselves in such descriptors. The truth, of course, is that they would not. Indeed the proclamation itself admitted as much, speaking of the “whole nation” but also “its parts,” a majority and a minority whose differences had been fostered by an alien presence and which would disappear when that alien presence disappeared. The foreigner had made Irishmen foreign to each other. Banish the foreigner. To put the point in Rousseau-ean terms, it was the General Will that was proclaimed at the General Post Office, all contrary views reduced to the status of ‘factions” which, eventually, would be “forced to be free.” The General Will, that seductive, coercive doctrine, has given moral force and sanction to any number of enormities committed in its name. In a famous set of lectures later published as Two Concepts of Liberty, Isaiah Berlin witheringly spoke of “one of the most powerful and dangerous arguments in the …history of human thought”: the notion that to liberate people “is to do just that for them which, were they rational, they would do for themselves, no matter what they in fact say they want.”[4] Souls must be engineered whether those souls wish to be engineered or not.

In that sense, one can almost hear in the proclamation a summons to moral unity that would be provided by the summons itself, its declarative certainties substituting for argument and making it redundant. “We have no misgivings, no self-questionings,” Pearse wrote. “While others have been doubting, timorous, ill-at-ease, we have been serenely at peace with our consciences…We called upon the names of the great confessors of our national faith, and all was well with us. Whatever soul-searchings there may be among Irish political parties now or hereafter, we go on in the calm certitude of having done the clear, clean, sheer thing. We have the strength and peace of mind of those who never compromise.”[5] What Chesterton called, in other circumstances, “healthy hesitation and healthy complexity” seems lacking.[6] The sheer thing was the right thing.

Yet the men of 1916 were in some ways as complicated, as variegated, as divided, as the history they proclaimed to be sheer and simple. Tom Clarke’s father was a cavalryman in the Royal Artillery, a member of the Church of Ireland, a veteran of the Crimean War. His brother also served in the army. Thomas MacDonagh’s father was a schoolteacher who rejected the Fenianism his son was later to embrace. His grandmother was an English Unitarian. Eamonn Ceannt’s father was a native Irish speaker who insisted that the family speak English. Ceannt taught himself Irish and persuaded the family to revert to it. Connolly served in the British army for seven years, admittedly calling it a “veritable moral cesspool,” a “miasma of pestilence” “most revolting” and “bestial.”[7] Joseph Plunkett, educated in England and deeply read in English literature, was a cosmopolitan mystic who discovered his Irishness almost as if discovering himself in an unknown country. “This island is fascinating” he said of a visit to Achill in 1909, sounding more like an anthropologist than himself an Irishman.[8] Sean MacDiarmada tried his hand at teaching, gardening, and tram-conducting before finding his vocation as a Sinn Fein organizer working mainly for the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The brotherhood, you sometimes feel, was almost as important to him as the Irish Republicanism, giving him a moral companionship otherwise unavailable to him.

And then there was Pearse – in some ways the most divided of them all. “Pearse, you are too dark in yourself,” he wrote in 1912:

Is it your English blood that is the cause of that, I wonder. I suppose there are two Pearses, the somber and taciturn Pearse and the gay and sunny Pearse. I don’t like that gloomy Pearse. He gives me the shivers. And the most curious part of the story is that no-one knows which is the true Pearse.[9]

His father Jim was himself a divided man – an Englishman living in Ireland, a free-thinker whose livelihood came from the Church, a pamphleteer whose tracts included The Follies of the Lord’s Prayer who died “fortified by the rites of the Roman Catholic Faith.”

“In you, our dead enigma, all the strains/Criss-cross in useless equilibrium.” Seamus Heaney’s lines in memory of the poet Francis Ledwidge, killed in France in July 1917, might apply to the men of 1916. All the strains crisscrossed on Easter Monday. All the deaths were enigmatic.

Too much may be made of this, of course. Which life does not have its complications, its angularities, its contingencies? These were human beings, not stock characters in a creaky Irish play. Reducing them to representative types – the Gaelic Leaguer, the Marxist autodidact, the Romantic poet – avoids the duty of understanding them. On the other hand, they did play their roles uncommonly well and, in the end, seemed almost to be doing impersonations of themselves, the masks hard to separate from the men. Swept along by the scripts they had written for themselves, they faced their appointment with destiny, going into battle, said Joyce Kilmer, “with a revolver in one hand and a copy of Sophocles in the other.”[10]

So, the strains crisscrossed in Easter week. One way of reading 1916 is to see it as the resolutions of these tensions, ending at a stroke the misgivings and soul-searchings in a supreme act of will which was not a demand for freedom but a personal expression of it. For Pearse and Plunkett, the Rising almost had the status of a work of art, its symbolism so obvious that even the most literal-minded reader could understand it. “I do not think the Rising week was an appropriate time for the issue of memoranda couched in poetic phrases, nor of actions worked out in a similar fashion,” Michael Collins later wrote. “Looking at it from the inside, it had an air of Greek tragedy about it.”[11] But even as Collins repudiated its artistry, he still saw it as art. Perhaps, in fact, there was a different aesthetic at work. Think for example of Schiller’s distinction between naïve and sentimental poetry. The first is unselfconscious, innocent, and childlike. The second is troubled, disturbed, and self-aware. Sentimental artists, as Michael Ignatieff has pointed out, make an art “out of their own alienation, their own inability to identify fully with their times or with their milieu.”[12] In that sense, some of the men of 1916 were sentimentalists, creating in their imaginations an Ireland uncontaminated by capitalism or colonialism so that they, too, could be purified and made whole when that Ireland achieved its freedom.

What that freedom would look like, of course, was never entirely clear. It was enough, for the time being, to defeat the enemy. The details could be sorted out later. Oceans of ink have been spilt comparing Connolly’s Ireland to Pearse’s; and rightly so, for serious matters were at stake. But an air of unreality hung over these debates before the Rising and, once it had started, an air of surrealism. As the bombardment of the GPO was getting under way, Pearse and Plunkett wondered whether Germany, their soon to be victorious ally in the war, would annex Ireland once the war was over. No, they thought. The better idea would be to establish an independent Ireland under Prince Joachim of Prussia, which “would encourage de-Anglicization because Joachim would favor the Irish language over English, since making the country German-speaking would be impossible. After the first generation or so, [Joachim] would have become completely Irish.”[13] This was – let us speak charitably – a fairly unhinged conversation.

By then, it was too late. Within days, defeat awaited, then surrender, then trials whose verdicts were foreordained, then a series of executions whose cruelty and stupidity stunned the world. The conclusion of George Bernard Shaw has been the conclusion of most historians: “It is absolutely impossible to slaughter a man in this position without making him a martyr and a hero, even though the day before the rising he may only have been a minor poet…The military authorities and the English government must have known that they were canonizing their prisoners.” “You are letting loose a river of blood,” said John Dillon in the House of Commons. “It is the first rebellion that ever took place in Ireland where you had the majority on your side. It is the fruit of our life work…and now you are washing away our whole life work in a sea of blood…It is not murders who are being executed; it is insurgents who have fought a clean fight, a brave fight, however misguided, and it would be a damned good thing for you, if your soldiers were able to put up as good a fight as those men in Dublin – three thousand men against twenty thousand with machine guns and artillery.”[14]

Dillon was right. Not even those who found fault with the insurgency faulted the insurgents as they faced their deaths. “I have had to condemn to death one of the finest characters I have ever come across,” Brigadier-General Blackader said of Pearse. “There must be something wrong in the state of things that makes a man like that a rebel. I don’t wonder his pupils adored him.”[15] Connolly’s last meeting with his wife was extremely poignant. The rest of them made their farewells in suitably dignified ways.

Their legacy has been disputed ever since. How could it be otherwise? The way Irish people view these seven men is the way they view themselves and the country bequeathed to them by their lives and deaths. But an Ireland that can remember both the GPO and the Somme a hundred years on has at least partially fulfilled the promise of the Proclamation to guarantee “religious and civil liberty” and to cherish “all of the children of the nation equally,” oblivious of differences. Such an outcome has taken too long and has entailed too much bloodshed along the way. But perhaps, almost in spite of ourselves, we are beginning to learn our history lessons. That is surely worth celebrating, perhaps even in an English-speaking Irish pub in Spain.

[1] For references in this paragraph, see Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Seven: The Lives and legacies of the Founding Fathers of the Irish Republic (Oneworld: London 2016), pp.49, 65, 129, 166, 187, 220.

[2] “Artists show mixed feelings are the heritage of the Rising” in The Irish Times July 30, 2016, p.8.

[3] Declan Kiberd, “Acting on Instinct” in The Times Literary Supplement, No. 5899, April 22, 2016, p.15.

[4] Michael Ignatieff, Isaiah Berlin: A Life (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998), p.202.

[5] Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Seven: The Lives and legacies of the Founding Fathers of the Irish Republic (Oneworld: London 2016), p.277.

[6] Kevin L. Morris (ed.), The Truest Fairy Tale: An Anthology of the Religious Writings of G.K. Chesterton (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 2007), p.14.

[7] Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Seven: The Lives and legacies of the Founding Fathers of the Irish Republic (Oneworld: London 2016), p.209.

[8] Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Seven: The Lives and legacies of the Founding Fathers of the Irish Republic (Oneworld: London 2016), p.186.

[9] Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Seven: The Lives and legacies of the Founding Fathers of the Irish Republic (Oneworld: London 2016), p.117.

[10] Briona Nic Dhiarmada, The 1916 Irish rebellion (University of Notre Dame Press: South Bend 2016), p.159.

[11] Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Seven: The Lives and legacies of the Founding Fathers of the Irish Republic (Oneworld: London 2016), p.319

[12] Michael Ignatieff, Isaiah Berlin: A Life (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998), p.223

[13] Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Seven: The Lives and legacies of the Founding Fathers of the Irish Republic (Oneworld: London 2016), p.318.

[14] Briona Nic Dhiarmada, The 1916 Irish rebellion (University of Notre Dame Press: South Bend 2016), p.161.

[15] Briona Nic Dhiarmada, The 1916 Irish rebellion (University of Notre Dame Press: South Bend 2016), p.148.

The Easter Rising is also known and sometimes is called the Easter Rebellion. A time in Ireland during Easter Week, April 1916, that will never be forgotten. A fight against British rule in Ireland, responded by British military.

The Easter Rising took place in Dublin, and a few outposts across the country: Skirmishes in counties Meath, Galway, Louth, Wexford and Cork.

it’s already 102 years…

In 2016 Ireland marked the centenary of The Easter Rising.

this is a lovely post, Nathaniel. Thanks for sharing . The Easter Rising is also known as the Easter Rebellion. ….to end British rule in Ireland. Patrick Henry Pearse was an Irish teacher, barrister, poet, writer, nationalist. Bet he is best known in Irish history as an activist and one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916. There is a Pearce museum in Dublin, which is dedicated to the memory of Patrick Pearse and his brother, William. Its free of charge, gives plenty of info and historical insights.

Dublin also has a number of historical places , where all the events took place.