The Prague Spring as Seen from the United States

By William J. Connell, LaMotta Chair and Professor of History, Seton Hall University

The Prague Spring had resonances in the United States that were quite different from those in Europe. To begin with, because 1968 was a year of great domestic upheaval, the events in Czechoslovakia appeared distant and even, in certain respects, quaint. At the time American society was trying to cope with a war in Vietnam that was becoming increasingly bloody, with no easy end in view. The assassinations of civil rights leader Martin Luther King and presidential candidate Robert Kennedy severely people’s faith in the ability of the political system to correct its shortcomings. Riots in African American ghettos and the rise of a Black Power Movement were countered on the opposite extreme by the presidential candidacy of a racist former Governor of the state of Alabama, George Wallace. The student occupation of buildings at Columbia University in April 1968 set off a wave throughout the nation of protests, occupations and riots at universities. Thus, while the Prague Spring was endorsed in the United States, both on the political left and the political right, in the mind of the American public the Prague Spring was perceived as a peripheral event, more like the student uprisings in Paris and Mexico City that year, than the serious challenge to Communist Party rule and Soviet domination that it really was.

Within the besieged American Establishment there were no doubt feelings of Schadenfreude stemming from recognition that Soviet leaders were confronting in Czechoslovakia some of the same idealistic turmoil that was then taking place in the US. Above all, it helps to remember that the US had already shown itself as embarrassingly helpless in 1956 in Hungary. There, although a revolt against the Soviet system had been encouraged by the Eisenhower administration, the government decided, as a matter of policy, to do nothing when it actually occurred. Thus, from the very outset of Dubček’s revolt within the Communist Party, although there was sympathy in Washington, it was recognized that the US would not provide material support for the Czech innovators in the event of resistance by revanchist Communists or of Soviet intervention. Moreover, the US decided against active propaganda measures on behalf of the new Czech regime on the supposition that these would make Soviet repression more likely. Without an official narrative of serious government support, the US media, always attracted to charismatic politicians, tended to treat the Czech reformers as utopians—much like the icons of domestic popular culture—who were only possibly the harbingers of a new age. There was little popular understanding in the United States that these were committed and serious politicians who were engaged in a fierce struggle.

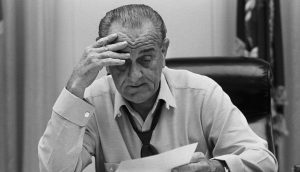

Thus, when the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact nations invaded Czechoslavakia on August 20, the American response was relatively weak. President Lyndon Johnson, who had already announced on March 31 that he would not seek re-election as President was focused during his last months in office on pursuing a policy of détente with the USSR that he hoped would reduce nuclear tensions while also facilitating an exit from Vietnam. Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador in Washington, in his memoir, related how he delivered an official announcement of the invasion to Johnson. He was astonished that Johnson said he knew there was a “crisis” in Czechoslovakia, but he believed it was internal and not caused by the Soviets, and he wanted to go ahead with a summit meeting planned with Soviet Foreign Minister Alexei Kosygin the following day on August 21. Only after he met with National Security Council officials did Johnson realize how politically unpractical that would be and cancel the meeting. The US did protest the invasion in the United Nations Security Council. And, in one of the most interesting developments, it gave a diplomatic warning to the USSR that if there were a similar invasion of Romania, the United States would take more forceful action. These, of course, were years when Romania’s established ruler, Nicolae Ceauşescu, was demonstrating independence from the Soviet Union in the realm of foreign policy, and the United States hoped that Romania might become a neutral state in the Cold War in the manner of Yugoslavia. The warning concerning Romania was prompted also by the country’s strategic significance as a nation on the Black Sea that had a long border with the USSR (now Ukraine and Moldova) and another border with Yugoslavia. Czechoslovakia, by contrast, had a tiny border with the USSR (now Ukraine), while being hemmed in by the hard-line states of the GDR and Hungary.

In subsequent months and years the United States did, however, turn the Soviet repression of the Czechs to its advantage. The shock of witnessing a coordinated invasion by Warsaw Pact forces (USSR, GDR, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria—Romania abstained) and the promulgation the following month of the Brezhnev Doctrine served as a wake-up call to the NATO countries. NATO had been languishing since France’s 1966 withdrawal of its troops from the alliance, but this show of power by the Warsaw Pact resulted in fresh commitments across the alliance, including a decision by the United States to continue its stationing of troops in West Germany.

What many in the intelligence community perceived as a “missed opportunity” in Czechoslovakia led to criticism and planning for the future, in the event of other protests against Communist regimes in Eastern Europe. Thus, in 1980, when the Solidarnosc movement in Poland took off, effective encouragement and material support were available. It was particularly important that this assistance not arrive directly from the US government, but instead from other sources more difficult to challenge. American labor unions, especially the AFL-CIO under the guidance of President Lane Kirkland, were able to offer major support to the Polish labor movement. The Catholic Church (under a Polish pope) had multiple avenues for providing funds and other assistance within a country that was predominantly Catholic.

In the early 1980s I happened to be working in Washington DC, where I knew a number of high-ranking officials in the US diplomatic service, as well several important journalists. I remember well a dinner party that was held by one of these journalists, Joseph Alsop, where the labor leader Lane Kirkland was also a guest. Since the situation on Poland was on everyone’s mind, Alsop, in an attempt to be outrageous, attracted everyone’s attention by proclaiming to great laughter, “The current Pope is a far, far holier person than that wretched Calcutta woman!” The “Calcutta woman,” of course, was Mother Teresa. Today, Mother Teresa and John Paul II are both saints in the Roman Catholic Church…

The role that was played in the Polish resistance by foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) was certainly noticed by many who were involved on both sides. For some parties it created an example to be avoided, and it thus explains the obsessive fear of foreign NGOs, recently expressed in the form of severe restrictions on their activity, by the likes of Vladimir Putin and Viktor Orbán. But nothing like what happened in 1980-1981 was imagined back in 1968, when the United States mostly sat on its hands.

The Prague Spring had one further result in that, in the US as in Europe, it put an effective end to the nostalgic idea that the international student movements that were mobilizing in that year might find support and an ally in the Soviet Union, which, after all, continued to promote and adhere to socialism under the label of “socialist materialism.” To be sure, a progressive distancing from Russian-influenced Communist parties had been going on for decades among many on the Left in the US, as in Europe: first after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, and then after the Hungarian repression of 1956. This was why so many in the younger generation perceived an urgent need for what they called a “New Left.” But there were always hopes harbored in certain quarters for a unification of the Lefts old and new. The suppression of the Prague Spring in 1968 instead demonstrated that such a united front would be impossible to achieve. For in August of that year the Communist East revealed itself to have an “Establishment” more grim and violent than the Establishments that students were marching against in the US and in Western Europe.

Originally published in: http://revistatimpul.ro/view-article/4177

William J. Connell

Holder of the La Motta Chair and Professor of History

Seton Hall University, USA

That’s nicely put. There was a kind of unmooring on the Left in the Western European countries and also in the US. The Brezhnev Doctrine was really hard to swallow. But Castro swallowed it, and with the consequences in the US that you suggest. When I wrote about this I happened to be thinking of Italian friends who joined the independent and more radical autonomi–autonomous Marxist movements–and left the PCI. Within the PCI there remained those who were the equivalent of the UK’s “tankies.” To preserve the PCI’s popularity and institutional role, however, Enrico Berlinguer took the whole party down the Eurocommunist route. He was thus accused of betraying Marxist principles both by the older tankies (who continued in their affection for Stalin) and the younger, radicalized autonomi (some of whom joined the Red Brigades).

As I recall, the few pro-Soviet types in the American radical youth movement were always of only marginal influence — seen as far too conservative and timid by the rest of us — but the Prague Spring really sealed off their influence. (In the UK where the Communist Party was still rather influential, especially in the trade union movement, the Prague Spring divided the Party into what become known as the ‘Eurocommunists’, and the ‘tankies’.)

Perhaps more important was that the influence of the Cuban Revolution and its leaders was given a serious setback. Many young American Leftists admired the recently-murdered Che Guevara … but when Fidel endorsed the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia … he wrote himself off among many in the New Left. He could no longer be seen as an idealistic model of self-sacrifice and struggle. That, and the repression of homosexuals in Cuba, meant that the New Left in the US, for good or ill, had no foreign models to follow.