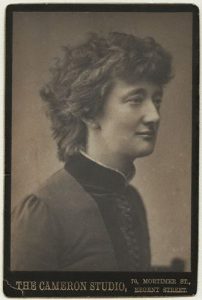

In honor of Lá Fhéile Pádraig (St. Patrick’s Day) and Women’s History Month, the name Alice Stopford Green is one that has a prominent place in the Scoláireacht Stairiúil ar Éire (Historical scholarship on Ireland) as one of the earliest twentieth century intellectual chroniclers who was able to write in depth with the benefit of diverse and multi-subject based primary sources about varied aspects of Irish history. In addition, she made her mark not only as one of the first female, but overall trailblazing members of Seanad Éireann (Irish Parliament) with the birth of the Irish Free State during the 1920s. The Archives & Special Collections has collected a number of her works which are featured a part of our Irish Book holdings library within the Archives & Special Collections Center.

A native of Kells, Alice Sophia Amelia Stopford entered the world on May 30, 1847, the seventh of ninth children born to Edward Adderley Stopford, who three years earlier was appointed the Archdeacon of Meath under the authority of her grandfather Edward (d. 1850), who was a former Bishop of Meath (1842-50), as part of the Church of Ireland (Anglican) hierarchy. (Johnston; Wikipedia). The Stopford family proper were long standing residents of Éire as contemporaries and acknowledged scholars who traveled with Oliver Cromwell and his adherents during their conquest of Ireland.

The migratory history of the Stopford clan also included ties to various family members residing in London. Periodic visits made by Alice to the largest city in Great Britain led to her meeting John Richard Green (1837-83), a combination cleric and scholar who would eventually become a noted historian in his own right with the publication of Short History of the English People (London: Macmillan, 1874).

Alice and John married in 1877 and she assisted her husband in his research and writing as a documenter of Irish heritage and she adopted his methodology in the process. Although John passed away in 1883, Alice rallied from this loss to become an active presence in the publishing world and began sharing her own work with the public (R.B. McDowell).

After repeated sojourns across the Irish Sea during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in 1918 Stopford Green permanently moved back to Ireland. Stepford Green would become a very passionate supporter of the Gaelic Revival and its goals for the preservation and proliferation of Irish language, scholarship, and political independence. As a result of her passion and persuasive nature Stepford Green helped to create and maintain a Celtic Studies program located in Dublin (Johnston).

Stepford Green also became involved with international movements in Africa, studied the colonial policies toward that continent, and advocated justice for the indigenous populations in relation to the quest for Irish independence.

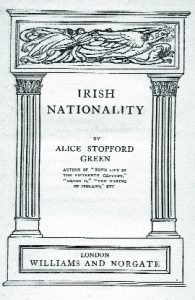

After the initial publication of her seminal work – The Making of Ireland and its Undoing, 1200-1600 (London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1908) where she explores the history of economics and education in the Irish experience, Stopford Green wrote two subsequent patriotic-themed books entitled: Irish Nationality (1911) and The Old Irish World (1912). These works written pre-Easter Rising continued in the nationalistic, yet scholarly vein (Wikipedia). Ironically, Stopford Green served as the first female president of the British Historical Association (1915-18), turning her pen towards producing essays and articles attempting to heal the escalating divisions in Irish society (Wikipedia).

Stopford Green was celebrated for her hopes for a distinctive Irish constitution, a parliament controlled by the Sinn Féin party (“We Ourselves”) and for re-examing the “Dominion Status” model found in Canada prior to their own independence (Wikipedia). She was also a confidant of Michael Collins and others in the Home Rule movement, along with being an occasional gun runner for the underground (Wikipedia). After the partition and Civil War (she was pro-Treaty) during the early 1920s, Stopford Green lived adjacent to St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin and kept up a busy social schedule, including frequent visits to the North of Ireland to keep in contact with friends across these counties and the Free State alike (Johnston).

In addition to her attention to intellectual and social affairs, Stopford Green was a co-founder of the Cumman na Saoirse (The League for Freedom) a female Irish Republican organization, along with becoming one of the first individuals nominated to serve in the newly formed Senate of Ireland (Seanad Éireann), and in the process she became one of the first four women elected or appointed to this chamber in 1922 and served as a member of this body until 1929 (Wikipedia; Mitchell 15). Stopford Green passed away on May 28, 1929 and was buried at Deansgrange Cemetery in Dublin. Her grave marker reads: “Historian of the Irish People” (Mitchell 15)

Within the holdings catalog of the Irish Book Collections found Archives & Special Collections included the following first edition volumes written by Alice Stopford Green . . .

- The Making of Ireland and its Undoing 1200-1600 (London: Macmillan 1908), Do., 2nd ed., with add. Appendix (Oct. 1909; rep. 1913),. xxiv, 573 pp.; Do. [another ed.] (London: Macmillan 1924), 573pp.; and Do. [rep. of 1st Ed.] (NY: Books for Libraries Press 1972), xvi, 511 pp.

- Irish National Tradition (London: Macmillan 1923), 31 pp. [rep. from History (July 1917)

- Irish Nationality [Home University Library of Modern Knowledge, No. 6] (London: Williams & Nordgate [1911], 1922, 1925), 256 pp.; [another ed.] (London: T. Butterworth 1929), 252pp. [also Irish trans., as infra].

- History of the Irish State to 1014 (London: Macmillan & Co 1925), xi, 437 pp., ill. [front. map; maps, plan].

- The Old Irish World (Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son 1912), vii, 3 lvs., 197 pp., ill. [pls., maps (1 fold.); 23cm.].

- The Irish and the Armada (Dublin: Cumann Léigheacht an Phobail 1921), 27 pp.

- An Irish School (London: Macmillan and Co. St. Martin’s Street, London, 1926), 15 pp.

https://setonhall.on.worldcat.org/search?clusterResults=off&queryString=stopford+green

For more information about Alice Stopford Green and her works (The Making of Ireland and its Undoing 1200-1600 in particular) please consult the following link to the journal Critical Inquiries Into Irish Studies – https://scholarship.shu.edu/ciiis/ under the Téacsúil Fionnachtain (“Textual Discovery”) entry, and/or you can contact via the following e-mail address: Archives@shu.edu or by phone at: (973) 275-2378.

Works Cited

“Alice Stopford Green,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/_wiki/Alice Stopford Green Accessed 1 January 2021.

“Alice Stopford Green (1847-1929),” Ricorso.Net, http://www.ricorso.net/rx/az-data/index.htm Accessed 1 January 2021.

“The Bookshelf – The Making of Ireland and its Undoing,” Irish Times & Weekly Times, 18 December 1909, 9.

“Ireland and the Tudors,” Irish Times & Weekly Times, 25 June 1908, 7.

Johnston, Roy. Century of Endeavour – Life and Times of Alice Stopford Green, 1999. http://www.rjtechne.org/century130703/1900s/asgmcd.htm Accessed 1 January 2021.

McDowell, RB. Alice Stopford Green – A Passionate Historian, Dublin, Allen Figgis, 1967.

Mitchell, Angus. “An Irishman’s Diary,” Irish Times & Weekly Times, 2 December 2019, 15.

“Mrs. Green’s History of Ireland – Mrs. J.R. Green’s Remarkable Volume on The Making of Ireland and its Undoing (1200-1600),” Irish Times & Weekly Times, 26 September 1908, 18.

“Noted Irish Writer – Death of Mrs. A. Stopford Green – Her Gift to Free State Senate,” Irish Times & Weekly Times, 29 May 1929, 7.

O’Brien, George. “Book of the Day – Passionate Historian,” Irish Times & Irish Weekly Times, 11 July 1967, 9.

SetonCat Entry. Seton Hall University Libraries, “Alice Stopford Green (1847-1929);” Stopford Green, Alice. The Making of Ireland and its Undoing, 1200-1600, MacMillan and Company, Ltd., 1909.

https://setonhall.on.worldcat.org/search?clusterResults=off&query String=stopford+green#/oclc/456747. Accessed 1 January 2021.

“Students’ Department – Selected Motto for 1908,” Irish Times & Weekly Times, 26 September 1908, 18.

“The Bookshelf – The Making of Ireland and its Undoing,” Irish Times & Weekly Times, 18 December 1909, 9.

“The Elected Members, Who’s Who of the Last Thirty,” Irish Times & Weekly Times, 16 December 1922, 5.